Active Consent in Corporate Governance: Mitigating Coerced Directorships through Annual Re-Verification

Submission by: Adjunct Professor Dr Brett Davies

SJD, MBA, LLM, LLB, BJuris, Dip Ed, BArts(Hons)

Adjunct Professor, The University of Western Australia & Adjunct Reader, Curtin University

Partner, Legal Consolidated Barristers & Solicitors

Abstract This paper constitutes a formal submission to the Australian Treasury’s consultation on ‘Combatting Financial Abuse Perpetrated through Coerced Directorships‘. It critically analyses the current registration framework under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), arguing that the existing ‘point-in-time’ consent model is insufficient to protect vulnerable individuals — specifically ‘passive’ directors — from financial abuse and strict personal liability for corporate tax. Drawing on the principles of Deputy Commissioner of Taxation v Clark, the paper demonstrates how the Australian Taxation Office’s (ATO) Director Penalty Notice regime penalises non-participation. It proposes a novel regulatory mechanism: a mandatory Annual Directorship Confirmation (ADC). By requiring directors to positively reaffirm their status annually via the Australian Business Registry Services (ABRS), this mechanism would serve as a circuit-breaker for coerced appointments and provide an evidentiary basis for relief from DPNs and other personal liabilities.

1. Introduction: The impact of Coerced Directorships on victims

While the ‘corporate veil’ traditionally protects directors from company debt, statutory piercing mechanisms — specifically the ATO’s Director Penalty regime — have turned the position of director into a mechanism for coercion and inescapable debt. The Treasury’s consultation, Combatting Financial Abuse Perpetrated through Coerced Directorships, identifies a critical failure in the current governance framework: the ease with which perpetrators can appoint and maintain victims as ‘straw’ directors to accrue tax and trading liabilities.[^1]

While the introduction of the Director Identification Number (‘Director ID’) regime was a significant step toward verifying identity, it does not verify ongoing consent. A victim may sign an initial consent form under duress — or have their digital credentials used without authority — and remain on the register for years.

This paper argues that the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (‘Corporations Act‘) must evolve from a model of ‘passive assumption’ of office to one of ‘active periodic verification’. It proposes the implementation of an Annual Directorship Confirmation (‘ADC’), a digital check-in system administered by the Australian Business Registry Services (‘ABRS’).

2. Legal Context: ‘Sleeping Directors’ and ATO Personal Liability

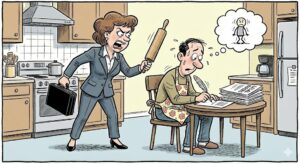

To understand the necessity of an ADC, one must appreciate the severe consequences of being a ‘passive’ or ‘sleeping’ director in Australia. The law generally does not distinguish between a director who actively manages the business and a spouse who merely signs documents at the kitchen table.

A. The Clark Principle: Why passive directors have no defence

The seminal case of Deputy Commissioner of Taxation v Clark (‘Clark‘)[^2] established that a director cannot rely on their own total failure to participate in management as a defence against liability. In that case, Mrs Clark, a ‘sleeping director’, was held liable for the company’s debts despite her argument that she left all decision-making to her husband.[^3]

While Clark specifically concerned defences regarding the non-remittance of tax, the principles regarding the objective standard of care are frequently applied to the ‘good reason’ defence for insolvent trading under s 588H(5) of the Corporations Act. This precedent cements the position that ignorance of company affairs is not a shield; rather, it is a breach of the director’s duty of care.

B. The ATO Director Penalty Notice (DPN) Regime

The Australian Taxation Office (‘ATO’) possesses strict statutory powers to recover company debts from directors personally. Under the Director Penalty Notice (‘DPN’) regime, directors are personally liable for the company’s unpaid Pay As You Go (‘PAYG’) withholding, Superannuation Guarantee Charge (‘SGC’), and — since 1 April 2020 — Goods and Services Tax (‘GST’).[^4]

Crucially, this liability is ‘parallel’ and ‘joint and several’.[^5] The ATO does not need to prove that the director was complicit in the non-payment; the mere fact of holding office is sufficient to attract liability.

- Lockdown DPNs: If a company fails to lodge returns within three months of the due date, the director becomes automatically and permanently liable for the debt. There is no ability to remit this penalty by placing the company into administration.[^6]

- Strict Liability for Passive Directors: The regime effectively holds passive directors to account. The rationale is that a director who permits themselves to be a ‘puppet’ facilitates the abuse of the tax system.

For a victim of coerced directorship, this is a legal trap. They are coerced into the role, kept in the dark about the company’s insolvency, and then suffer personal liability for tax debts they did not know existed.

3. The Proposal: A Mandatory Annual Directorship Confirmation (ADC)

To prevent the accumulation of debt in the name of an unsuspecting or coerced victim, the registry system must interrupt the perpetrator’s control.

A. The Mechanism: Direct contact via Director ID

It is proposed that the ABRS implement an automated annual trigger, distinct from the company’s annual review fee.

- Direct Contact: Each financial year, the ABRS sends a secure notification (email or SMS) directly to the contact details linked to the individual’s personal Director ID profile, not the company’s registered agent.

- Positive Affirmation: The director must log in (e.g., via the Commonwealth’s myID) and click a simple affirmation: ‘I confirm I am currently a director of [Company Name] and consent to remain in this role.’

- The ‘Circuit Breaker’: If the confirmation is not received within a set period (e.g., 28 days), the directorship is flagged on the public register as ‘Unconfirmed’. Continued failure to confirm could trigger an administrative process to verify the director’s status or limit the company’s ability to lodge certain documents.

B. Advantages: Stopping financial abuse early

This proposal offers three distinct benefits over the current passive model:

- Bypassing the Perpetrator: In many cases of domestic financial abuse, the perpetrator controls the company mail and the ASIC agent portal. By linking the ADC to the individual’s private Director ID contact channel, the system bypasses the perpetrator’s gatekeeping.

- Mitigating ATO Liability: If a victim does not confirm their directorship, this provides contemporaneous evidence that they were not consenting to the role for that period. This could be used to support a defence against a DPN, distinguishing their situation from the voluntary passivity seen in Clark. Further, the Treasury needs to legislate that an “Unconfirmed” status creates a rebuttable presumption that the individual was not acting as a director. Without legislative backing, the ATO might argue that the person was still a director de jure, even if they did not click the button.

- Operationalising Clark: Since Clark requires directors to be active, the ADC system forces a moment of activity. It serves as a reminder to ‘sleeping directors’ of their obligations, potentially prompting them to resign before tax liabilities crystallise. It provides a structured ‘exit ramp’ for passive directors. Many spouses do not know how to resign; an annual prompt with a ‘No / I wish to resign’ option empowers them to leave potentially before insolvency events.

C. Enforcement: Operational Consequences for Non-Compliance

To ensure the ADC is not treated as a mere administrative suggestion, failure to confirm a directorship must result in immediate operational friction for the company. A ‘passive’ register allows fraud to fester; an ‘active’ register must reject non-compliant entities.

It is proposed that a status of ‘Director Unconfirmed’ trigger the following cascading sanctions:

- Public Warning (The ‘Red Flag’): The ASIC and ABRS public registers immediately display a “Director Status: Unconfirmed” warning. This signals to creditors, banks, and suppliers that the company’s governance is in doubt, effectively freezing its creditworthiness.

- Administrative Freeze: While a director remains unconfirmed, the company is blocked from lodging key administrative documents (e.g., ASIC Form 484 Change to Company Details). This prevents perpetrators from cycling through new unsuspecting directors to facilitate illegal phoenix activity.

- Referral for Deregistration: If a company lacks a confirmed director for a statutory period (e.g., 6 months), this should constitute grounds for ASIC to initiate administrative deregistration under s 601AB of the Corporations Act. A company without confirmed active management cannot be permitted to trade.

- ATO Data Matching: An ‘Unconfirmed’ status triggers a high-risk flag within the ATO’s systems, prompting a review of recent BAS lodgements and potentially pausing tax refunds until the governance structure is verified.

4. Addressing Regulatory Burden and Compliance Costs

Critics may argue that an ADC increases red tape. However, the friction is minimal — a ‘one-click’ process comparable to confirming a tax return. For legitimate directors, it is a 30-second task. For victims of coercion, it is a vital safeguard. The minor administrative cost is vastly outweighed by the system integrity gained by ensuring the registry reflects reality.

5. Conclusion on how to protect passive directors

The digitisation of Australian business registries offers a unique opportunity to embed safety by design. A passive registry facilitates abuse; an active registry deters it. By mandating an Annual Directorship Confirmation, the Treasury can ensure that the corporate structure does not become a tool for financial abuse. This reform would operationalise the government’s commitment to reducing harms from coerced directorships by ensuring that consent is not just a one-off signature, but a continuing, verifiable reality.

Footnotes

[^1]: Treasury (Cth), Combatting Financial Abuse Perpetrated through Coerced Directorships (Consultation Paper, November 2025) 5.

[^2]: (2003) 57 NSWLR 113 (‘Clark‘). https://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdoc/au/cases/nsw/NSWCA/2003/91.html

[^3]: Ibid [143] [127] (Spigelman CJ). In Clark, the Court of Appeal overturned the initial decision which had been favourable to Mrs Clark, establishing that a ‘total failure to participate’ is not a ‘good reason’ for non-participation under the relevant tax defence provisions; see also Morley v Statewide Tobacco Services Ltd [1993] 1 VR 423.

[^4]: Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) sch 1 s 269-10; Treasury Laws Amendment (Combating Illegal Phoenixing) Act 2020 (Cth) sch 3 (inserting GST, LCT and WET into the director penalty/estimate framework, operative 1 April 2020).

[^5]: Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) sch 1 ss 269-40 — 269-45. These sections provide the mechanics for the reduction and discharge of director penalties, establishing that payment by the company reduces the director’s personal liability (and vice versa), creating a ‘parallel’ liability structure.

[^6]: Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) sch 1 s 269-30(2); Australian Taxation Office, ‘Director Penalty Notice‘ and Practice Statement Law Administration PS LA 2011/14. Under the ‘Lockdown’ provisions, if a company fails to lodge BAS or IAS returns within three months of the due date (or SGC statements by the due date), the director loses the ability to remit the penalty by placing the company into administration. The liability becomes permanent.

Bibliography

- Articles/Books/Reports

Treasury (Cth), Combatting Financial Abuse Perpetrated through Coerced Directorships (Consultation Paper, November 2025). https://consult.treasury.gov.au/c2025-719210

- Cases

Deputy Commissioner of Taxation v Clark (2003) 57 NSWLR 113. https://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdoc/au/cases/nsw/NSWCA/2003/91.html

Morley v Statewide Tobacco Services Ltd [1993] 1 VR 423. https://victorianreports.com.au/judgment/view/1993-1-VR-423

- Legislation

Corporations Act 2001 (Cth).

Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth). https://www.legislation.gov.au/Series/C1953A00001

Treasury Laws Amendment (Combating Illegal Phoenixing) Act 2020 (Cth).

- Other

Australian Taxation Office, ‘Director Penalty Notice’. https://www.ato.gov.au/individuals-and-families/paying-the-ato/if-you-don-t-pay/director-penalty-regime