Professor Davies declares NSW electronic Will signing law a failure

NSW reckless in its failed attempt to allow people in NSW to sign Wills electronically.

As of 22 April 2020, in NSW, video conferencing technology like Skype, WhatsApp, FaceTime and Zoom are used in witnessing important legal documents like Wills, powers of attorney and statutory declarations. Documents include:

- an Australian Will

- a 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Will

- an Australian international Will signed under the Hague Convention

- enduring power of attorney

- Medical POAs, Guardianships, Directives & Medical Treatment Decision Maker

- Loan to Children Deed

- a statutory declaration and an affidavit

An “audiovisual link” is defined as technology that enables continuous and contemporaneous audio and visual communication. This is between persons at different places, including video conferencing. Given the weak Internet thanks to the ineffective NBN good luck with the ‘continuous’ requirement.

Does it include a Will maker signing in London, while one witness is in Hobart and the other witness is in Spain? Do you need to be in NSW or Australia for that matter? The Will, at best, only operates for assets you have in NSW. NSW is not a signatory to the Hague Convention (only Australia is). If you have a bank account with the NAB then you need to be Victorian law compliant. Contrary to what we think, NSW is not Australia.

These new rushed regulations are made under section 17 of the Electronic Transactions Act (NSW). It is a brave person who relies on such unusual and untested methods of witnessing. For example, a reporter telephoned me under the belief that a wet signature is no longer required. The NSW new legislation says nothing of the sort.

What does the person witnessing the document write on the Will? Would you need to put

‘this document was endorsed and signed in counterpart and witnessed over an audiovisual link in accordance with clause 2 of Sch 1 to the Electronic Transactions Regulation 2017 (NSW)‘?

What a mouthful. What does ‘endorsed’ and ‘counterpart’ even mean? In 40 years when you die who is going to remember this weird piece of legislation?

Instead, follow the above best practice rules for signing a Will in isolation and in a hospital.

Need help signing a Legal Consolidated Will and POA? Our Wills and POAs are supported for the rest of your life. You can update your Wills and POAs for free. For help signing Legal Consolidated Wills and POAs, telephone the law firm.

Victoria’s reckless ‘temporary’ electronic signing rules do not work – use a wet signature

Temporary changes in Victoria are meant to allow the electronic signing of Wills. This quick legislation is flawed.

Supposedly, this is to allow you to sign remotely:

- powers of attorneys

- Wills and 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Wills

Even the name of the act and regulation smacks of a government department out of control and out of its depth:

COVID-19 Omnibus (Emergency Measures) Act 2020

COVID-19 Omnibus (Emergency Measures) (Electronic Signing and Witnessing) Regulations 2020

The changes are in place until revoked. Documents signed under this temporary legislation are meant to remain valid. But on a careful reading of the legislation, we doubt that this is the case.

Bizarrely, under your electronic signature, you have to write a “statement”. In NSW, you are given no help with this. In Victoria, there is a suggestion you write this:

This document was electronically signed under the COVID-19 Omnibus (Emergency Measures) (Electronic Signing and Witnessing) Regulations 2020.

But few lawyers, and even the regulators themselves, do not believe this is the best wording. What is the best wording? No one knows.

Now that the Coronavirus is long gone, anyone who went down this rocky road risks having invalid Wills and POAs.

Even before COVID-19, about a third of homemade POAs are invalid. And about 12% of lawyer-prepared POAs are invalid. Relying on these hasty electronic signature rules only worsens the odds that your Wills and POAs are effective.

“Counterparts” The Victorian regulation also expressly contemplates signing a document electronically in “counterparts”. “Counterparts” is where a number of people print out the same document but sign it in different locations (see below). You collect them all up, and together, they are the document. Sadly, Victoria is imposing an additional requirement that each person whose signature is required on the document or whose consent to electronic signing is required receives a copy of each signed counterpart. See COVID-19 Omnibus (Emergency Measures) (Electronic Signing and Witnessing) Regulations 2020 (Vic) Pt 2 reg 12. This is a most unnecessary burden, which NSW rightfully refused to put in its legislation.

Queensland opens Pandora’s box – electronic signing of documents fails

Queensland also, in a fit of panic, passed a sweeping package of regulations that allow deeds, mortgages, general powers of attorney, affidavits, and declarations to be signed electronically on a temporary basis.

QLD shamelessly copies the Victorian approach. But improves on it. But then goes off on a frolic of its own to create new nightmares.

Like NSW, the ACT, Victoria and other States, the changes are meant to permit documents to be witnessed via audiovisual (AV) links. This was just another knee-jerk reaction to the COVID-19 pandemic. See COVID-19 Emergency Response—Wills and Enduring Documents) Regulation 2020 QLD.

Queensland introduced the Justice Legislation (COVID-19 Emergency Response—Wills and Enduring Documents) Regulation 2020 (QLD) These QLD Regulations are then updated by the Justice Legislation (COVID-19 Emergency Response—Wills and Enduring Documents) Amendment Regulation 2020. And amended, yet again, by the COVID-19 Emergency Response and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2020.

You read all of the above legislation together. Good luck with that. QLD provides that an instrument still takes effect as a deed. This is even if it is not written on paper, parchment or vellum. This is the only Australian state that expressly includes wording for the common-law rule that a deed is written on paper, parchment or vellum.

Qld Deeds: Because of poor language, it is not certain whether “Deeds” in general can be witnessed electronically in other States. But in QLD the regulations explicitly remove the requirement for a deed to be made on paper or parchment and for a deed signed by an individual to be witnessed. I still do not like the QLD regulations, but at least they have done better than their southern brethren.

Wills and POAs: The QLD regulations allow enduring powers of attorney and advance health directives (strangely called ‘enduring documents’) and Wills to be witnessed via AV link by a “special witness”. A special witness who witnesses the signing of a document via AV link signs a certificate that is kept with the document and states particular matters, including that the document was signed and witnessed under the regulations. What that wording is, no one knows. But no doubt the Qld court will work that out in 20 years when these time bombs come before the Courts.

Like Pandora’s box, this gift from the QLD State government seems valuable but is, in reality, a curse to your loved ones.

South Australia’s electronic signing – does not work, but did a better job than NSW and Victoria

South Australia copied NSW and Victoria. That is a mess. But with one improvement.

About remote witnessing, the Act specifically provides that a requirement for two or more persons to be physically present is satisfied if the persons meet or the transaction takes place remotely using an audio link, audio-visual link or any other means of communication prescribed by the regulations.

However, regulations specifically exclude any:

“requirement that a person be physically present to witness the signing, execution, certification or stamping of a document or to take any oath, affirmation or declaration in relation to a document …[from the remote meeting permission]”

This prevents the kind of remote witnessing and attestation of signatures or verification of identity, which is permitted in NSW and Victoria.

Western Australia gets in on the electronic act

See Covid-19 Response and Economic Recovery Omnibus Act 2020 (WA) pt 2 div 4 (in operation until 31/12/2022: Covid-19 Omnibus Act 2020 Postponement Proclamation 2021).

It allows AV link to sign and witness certain documents (e.g., affidavits and statutory declarations, but not wills).

Again, do not take the bait. Go back to old school.

Australian company Constitutions do not allow electronic signing

The Federal Government temporarily modified the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). See Corporations (Coronavirus Economic Response) Determination (No. 1) 2020. This was in May 2020. The Determination provides relief for companies. This is to execute documents electronically. The Determination was extended to 21 March 2021.

Does this work? Under section 127(3) Corporations Act a company may execute a document as a deed. This is if:

- the document is stated to be a deed and is executed as a deed; and

- it is executed under section 127(1) or 127(2)

Section 127(4) clarifies that section 127 does not limit how a company may execute a deed. Section 127(3) Company Act does state that a company may execute a deed if it is expressed to be a deed and executed under s 127(1) or (2).

We are worried. There is nothing in the Determination to expressly deal with the common law requirement. This is that a deed is made on paper, parchment or vellum.

Further, a Company Constitution sets out the rules that govern the company. No matter what legislation is passed the Company only acts under its own rules. Now you can amend the Company Constitution here. This allows electronic signing if the relevant State allows for it. But we recommend you sign nothing electronically.

All of these Constitution updates allow for electronic signing:

- Convert your company to a Special Purpose Company to be a trustee of an SMSF

- Convert your company from a Special Purpose Company to a ‘normal’ company

- Convert to a Company Constitution from Memo & Articles of Association

Federal Government and electronic signing – Virtual AGMs and electronic communication

The Corporations Amendment (Meetings and Documents) Act 2022 passed the Senate on 10 February 2022

The changes allow companies to:

- hold physical and hybrid meetings and, if expressly permitted by the company’s constitution, wholly virtual meetings.

- ensure that technology used for virtual meetings allows members to participate in the meeting orally and in writing;

- use technology to sign documents electronically, including corporate agreements and deeds; and

- send documents in hard or soft copy and give members the flexibility to receive documents in their preferred format.

Again, Legal Consolidated Constitutions are updated with these powers. It is better to have face-to-face meetings where possible.

Signing Deeds, Wills and POAs electronically

In Australia, a deed is a special type of agreement. It has specific requirements to be valid. The unique characteristics of a deed pose challenges due to its formalities.

A deed differs from a regular agreement in two ways:

- Firstly, there’s no need to fulfil the “consideration” element. This means a party does not have to provide something in exchange for the deed to be legally binding. This is because a deed holds a distinct quality. When a party signs it, they’re committing to the wider community that they’ll honour their promise.

- Secondly, the process of signing a deed is distinct in both form and content. Once a party signs a deed, they are immediately bound by its terms. This is unlike a mere agreement. Additionally, for a deed to hold legal weight, it must be in writing, signed, and witnessed. Key phrases often used in deeds include “executed as a deed” and “signed, sealed, and delivered.” If there are inconsistencies in the language used in the document, like referring to it as both an agreement and a deed, confusion arises about its intended nature. The case of 400 George Street (Qld) Pty Ltd v BG International Ltd [2010] QCA 245 illustrates the challenges that arise when these distinctions aren’t addressed.

Do not sign your Will electronically – Re Curtis [2022] VSC 621

In the landmark decision, Re Curtis [2022] VSC 621, we offer this information for those engaged in estate planning, particularly concerning the norms for electronic signatures and the observation of Wills via remote means as per the recently established section 8A of the Wills Act 1997 (Vic).

Re Curtis – Victorian Supreme Court

Re Curtis underscores the necessity for legal professionals who have overseen the remote signing of wills to reassess these documents. This reassessment ensures compliance with the detailed procedures outlined in the judgment. If discrepancies are found, it is advisable to either re-sign these Wills traditionally in person – with a wet blue biro (RECOMMENDED) or remotely follow the correct protocol (NOT RECOMMENDED).

Introduced as a provisional and rushed step during the COVID-19 health crisis on 12 May 2020, electronic Will signing was enabled by the Victorian government under the COVID-19 Omnibus (Emergency Measures) (Electronic Signing and Witnessing) Regulations 2020 (Vic). These regulations stopped on 26 April 2021, succeeded by a lasting protocol (which is also very flawed and reckless) for remote execution embedded within section 8A of the Wills Act.

The case of Re Curtis marks the first examination of these new procedures, highlighting the challenges faced in ensuring that witnesses adequately observe the will-maker’s signature process via electronic means. The court stressed the importance of witnesses being able to see both the act of the will-maker applying the signature via a device and the signature itself materialising on the document.

Background facts of Re Curtis

On 7 June 2021, Mr Curtis signed his Will through an audio-visual link during a period of stringent public health measures that confined residents of Melbourne to their homes. He signed the Will using the DocuSign software while his witnesses joined via a Zoom call and appended their signatures similarly. However, critical aspects of the electronic signing, such as the visibility of the device used for signing, were not within the witnesses’ view.

Following Mr Curtis’s death on 21 June 2022, the signing of his Will came under scrutiny due to uncertainties around its compliance with the remote execution requirements, specifically section 8A(4)(a) of the Wills Act. The stipulation demands that all witnesses must have a clear view of the signature being applied in real-time, either through an audio-visual link or by a combination of physical presence and remote connection.

What does Re Curtis teach us about electronically singing Wills?

Re Curtis serves as a reminder of the intricacies involved in remote Will signing. It is critical for both will-makers and witnesses to strategically position their cameras and utilise screen-sharing to ensure all parties can visibly confirm the signing process. Furthermore, verbal confirmations should be obtained during the signing to affirm that all participants have witnessed the signatures as they are applied.

Witnesses who are foolhardy enough to attempt the electronic signing of Wills are advised to document each step of compliance with the remote execution protocol comprehensively, including explicit details of how signatures were observed.

While the law does not mandate video recordings during the execution of Wills, they are considered best practice if you must go down this rocky road. Recordings can provide essential confirmation that the procedures were followed correctly and may support applications for probate under section 9 of the Wills Act. Even then, we have seen many fail evidentiary.

Legal Consolidated Barristers & Solicitors recommend revisiting any remotely signed Wills to verify adherence to the standards outlined in Re Curtis. Non-compliant Wills should be properly executed again, either in person or remotely, following the established guidelines. The best practice is to resign face to face with a wet blue pen. Do not take this unnecessary and foolhardy risk.

Signing Family Trust deeds electronically

All deeds, such as Unit Trusts, Bare Trusts, Partnership Deeds, etc… have their peculiar set of rules.

Here, we are just discussing Family Trusts deeds. This is to show how risky it is to have Deeds signed electronically.

Your accountant updates your Family Trust deed on average every 6 years. Family Trust deeds go out of date and need to be serviced like a car. So, let’s say your Family Trust is 20 years old. It has, say, been updated 3 times. That means that you have 4 deeds for your one Family Trust.

You go to the bank to open a new bank account for your Family Trust. You take in the 4 deeds. One, however, is not the original. Instead, it is a copy of the original duly certified by a JP. Your bank refuses to open the bank account. It only accepts originals. That is a Family Trust deed with a (hopefully blue) wet signature. If the bank is that strict, do you think it will tolerate your shenanigans regarding electronic signatures?

Your bank can ‘certify’ a Family Trust deed, but if you lose the original, you are stuck using that bank for the rest of your life. You cannot go to another bank with a photocopy of the original trust deeds.

Yet, ironically, the bank often requires that their mortgages be signed electronically!

Commonwealth government muddies the water with its version of electronic signing

The regulatory framework for the recognition of electronic communications, including electronic and digital signatures in Australia, is the Electronic Transactions Act 1999 (Cth). Sadly, it conflicts with State and Territory rules which have enacted their versions.

Despite the growing use of electronic signatures, the 2016 ruling by the NSW Supreme Court in Williams Group Australia Pty Ltd v Crocker [2016] NSWCA 265 emphasises that risks remain linked to this form of signing. In the Williams case, a creditor of a company is unable to enforce a director’s guarantee that is signed using an electronic signature. The court confirmed the trial judge’s finding that a company director’s electronic signature had been placed on a credit application and guarantee by an unknown person without his knowledge or authority and that the guarantee was not enforceable against him.

State electronic rules only work in that particular state

The rules for electronic signing in Australia apply individually to each state. However, these rules might not hold up when you’re attempting to enforce a document in a different state. This means that electronic signatures that are legally valid in one state might not necessarily be recognised or accepted in another state when it comes to enforcing the document’s terms.

You can not take these ‘unsigned’ documents across state borders. For example, the Victorian rules for electronic signing only apply in the State of Victoria. Good luck crossing the border into NSW and trying to use that Deed. Even worse if you want to use the document in another country.

Submitting electronic documents in Court

While electronic signatures may be legal in some states, the same document is not legal in another state; another problem is when you want to use the document in court.

From what we are seeing, the judge is looking for you to prove that there wasn’t any tampering after the document was “signed”. This is an extra burden. Often the other side is also forcing you to prove that the document was signed correctly. Everything is new. There are no seminal cases in Australia setting out the courts’ approach to electronic signatures. Every state is going its own way. It is a mess.

If a judge finds any reason to doubt the authenticity of an e-signature, they declare it inadmissible. For an electronic signature to hold up in court, it can’t have any weaknesses. A USA Court has rejected a DocuSign for bankruptcy petitions.

We have little direction from the Australian Courts on signing electronically

The Law Council of Australia has been silent. But the American Bar Association has said (the tortious misspelling of English by our American friends has been left uncorrected):

“Electronic signatures present unique issues in litigation.

For example, an electronic signer can more easily deny that he actually signed the document. It may be difficult to determine how to lay the proper foundation for an electronic signature.

Electronic signatures also allow corporate entities to argue that the signor did not have the authority to bind the entity. For example, in April 2018, the North Carolina Court of Appeals affirmed a summary judgment for Bank of America based in part on DocuSign records. IO Moonwalkers, Inc. v. Banc of America Merchant Services, 814 S.E.2d 583 (N.C. App. 2018). Though the court upheld an electronically signed contract, it did so based on a theory of ratification, highlighting the risk that in the case of a disputed electronic signature, a party seeking to enforce the signature may need additional evidence beyond the mere digital trail.

Banc of America Merchant Services (BAMS) provided credit card processing services to IO Moonwalkers (a company that sells hoverboard scooters). A dispute arose between the parties over chargebacks for fraudulent purchases and Moonwalkers claimed that t it never electronically signed the contract with BAMS. In its motion for summary judgment, however, BAMS produced DocuSign records showing the date and time that someone using the Moonwalkers company email viewed the contract, signed the contract, and later viewed the final, fully executed version. Moonwalkers did not dispute the records but claimed that the signer was not authorized to do so.

Electronic Will evidence is doubt

Luckily for BAMS, the trial court held, and the appellate court agreed, that the evidence confirmed that Moonwalkers ratified the contract. The trial court noted that “the electronic trail created by DocuSign provides information that would not have been available before the digital age—the ability to remotely monitor when other parties to a contract actually view it.”

But the court did not hold that those records, in and of themselves, established that Moonwalkers’ authorized representative had signed the contract and bound Moonwalkers. Instead, the court held that DocuSign records confirmed that Moonwalkers had reviewed and was aware of the contract’s terms. That, coupled with Moonwalkers other actions in abiding by the terms of the contract and responding to BAMS’s requests for information or materials required under the contract, led the court to hold that Moonwalker had ratified the contract. DocuSign records were critical evidence, but not in and of themselves dispositive of the validity or binding nature of the contract.

Practitioners need to weigh the convenience of electronic signatures against these potential problems—especially in large transactions that could end in litigation.”

Getup Ltd v Electoral Commissioner (2010) – electronic signing a mess

In this Federal Court case of Getup Ltd v Electoral Commissioner [2010] FCA 869, the court examined whether an electronic signature could be accepted for voter enrollment applications. The applicant, Getup Ltd, had provided an enrollment form with a digital signature, which the Australian Electoral Commission initially rejected. The court ruled in favour of the applicant, stating that the electronic signature met the necessary legal requirements, thereby allowing Australians to enrol online in future elections.

On 13 August 2010, the Federal Court of Australia ruled that electronic signatures could be valid for voter enrolment. The case arose when the Australian Electoral Commission rejected first-time voter Sophie Trevitt’s application, claiming her digital signature did not meet legal requirements. GetUp! challenged this under the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918. The court found in favour of GetUp!, confirming that electronic enrolment was legally valid. This decision allowed Australians to enrol online for future elections.

This case highlights the legal confusion of electronic signatures in Australia. The validity of electronic signatures tortiously depends on the specific context and the type of document involved. ‘Wet ink’ signatures are always safer.

Do not take risks – sign all documents with a wet blue biro

The ongoing attempts by Australian states to implement electronic signing and witnessing of legal documents such as Wills and Powers of Attorney highlight a reactionary approach driven by the exigencies of the now long-gone COVID-19 pandemic.

While these measures aimed to maintain legal processes during unprecedented times, they have introduced significant complexities and potential legal vulnerabilities. The lack of uniformity across states, the ambiguous legal wording, and the reliance on technologies that may not ensure the integrity and authenticity required for such sensitive documents create a landscape ripe for future legal challenges.

Our criticism of NSW’s electronic Will signing law as a failure underscores the broader issues in adopting electronic legal processes without thorough vetting and consideration of long-term implications. As we navigate the post-pandemic world, it becomes imperative to critically assess these temporary solutions and strive for comprehensive, secure, and universally accepted legal frameworks for electronic documentation. This will safeguard the interests of individuals and ensure that their legal intentions are honoured without ambiguity or dispute.

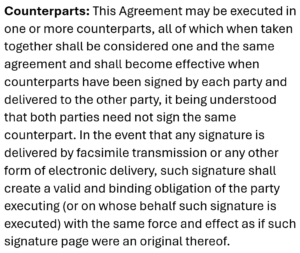

How to Sign a Document in Counterpart: An Alternative to Electronic Signing

This is a Counterpart clause I wrote in 1988, before plain English drafting.

I have been using it in my lecture notes—until last year when a student innocently asked, “Professor Davies, what is a facsimile?”

Avoid the fad of electronic signing for important documents. When you build a legal document on our website, it includes a ‘counterpart’ clause. This option is not available for Wills and Powers of Attorney but allows other legal documents and trust deeds to be signed in counterpart. Each party signs a separate but identical copy of the document at different locations, each considered legally original.

How Counterpart Signing Works

Two business owners—one in Brisbane and the other in Docklands, Victoria—each sign a copy of the contract. While a witness must be physically present for each signing, the other business owner does not need to be. Though signed separately, these copies are recognised together as a single enforceable document under the law.

Benefits of Counterpart Signing

This traditional method complies with legal standards across Australia, ensuring safety and legal validity.

Is signing in Counterpart common?

Yes. Signing documents in counterpart is a common practice in contract law that allows each party to sign separate copies of the same agreement, which together are considered legally binding. This method is particularly useful when parties are geographically dispersed or when quick execution is necessary. For instance, during transactions where immediate action is required, counterpart signing can ensure the agreement progresses smoothly without the logistical challenge of having all parties sign a single document.

The legal basis and practice of signing in counterpart are well-supported in various jurisdictions.

Signing the same document on different days at different locations

If you have the time, an alternative to signing in Counterpart is to courier or post the same document from person to person. One person signs in Burnie, Tasmania. The document is then sent to North Sydney, where another party signs. It is then sent to Darwin for another signature before finally arriving back at head office in Melbourne. This is legal and valid, provided each person signs the same physical document in turn.

This method ensures that all parties sign the same original document, making it a legally recognised way to execute agreements.

Under Australian law, for a document to be legally binding, each party must intend to be bound and execute the document correctly. Some documents, such as deeds, have stricter rules. A deed may require a witness, and that witness must be physically present at the time of signing.

Sending a single document from person to person for signing is a legally valid method of execution, provided all legal requirements for that document are met.

One problem is that the deed is not fully binding until the last party signs, which allows any party to withdraw before completion.