The Dangers of “Exotic” Powers of Attorney

Sometimes clients want to add additional clauses to their POA. These additions backfire and increase the risk that banks, land titles offices and government agencies will reject your POA.

Instead, to have the highest chance of a POA being accepted, they should be legally precise, with no restrictions and no special clauses. They should be drafted with one goal: to have the highest chance of being accepted without delay, without doubt, and without extra cost to your family.

Dangers of adding additional clauses to your POA

These are the continual messages from banks, title offices, and government departments across Australia regarding the problems with adding additional clauses to POAs in any state or territory.

1. Strict Legal Interpretation & Ambiguity

Australian courts interpret POAs very literally. If you include a clause granting the power to “sell and lease,” for example, the attorney might not be allowed to lease with an option to purchase unless that’s explicitly stated. Any non-standard clause can lead to confusion or limit the attorney’s ability to act legally.

2. Increased Risk of Disputes & Legal Costs

If a POA lacks clarity on certain powers—such as authorising a transaction that could pose a conflict of interest—the attorney may need to seek Supreme Court approval.

3. Witnessing & Acceptance Difficulties

Many jurisdictions require POA documents to be witnessed under strict conditions. If a clause is additional or unusual, a registrar or witness may refuse to validate it.

In some states, a court official is one of the few people who can witness and an enduring POA, and from experience, they will go out of their way not to witness anything that looks different.

4. Heightened Potential for Misuse or Elder Abuse

While conditions can help prevent misuse, additional clauses lead to misunderstandings and can be exploited. Overspecified, exact powers or restrictions unintentionally undermine the attorney’s ability to act in your best interest. Attempted legal safeguards—like requiring evidence from multiple professionals before acting—end up as an obstruction. There is already a requirement for the attorney to act in your best interests.

5. Complexity Hampers Clarity & Third-Party Acceptance

Banks, title offices, and other institutions process POAs frequently—but they rely on standard, familiar documents. If your POA has unusual or bespoke clauses, these institutions hesitate to accept them or impose extra verification hurdles.

6. Balancing Flexibility vs. Precision

While adding additional conditions can feel prudent—such as requiring that two doctors confirm incapacity or that attorneys require unanimous consent—these clauses result in confusion. Local regulators do not have the time to review clauses that they have never seen before.

Why Australian Banks Reject Non-Standard Power of Attorney Clauses

Don’t turn your Power of Attorney into experimental legal art, as banks are notoriously terrible critics and reject anything they don’t recognise.

A POA meticulously drafted by a law firm like Legal Consolidated isn’t about creative flair; it’s about being flawlessly engineered for the one thing that matters: immediate acceptance.

Our warnings about adding unnecessary powers to a Power of Attorney come from 4,600 financial planners, lawyers and accountants. These professionals build Powers of Attorney and Medical/Lifestyle documents on our website. Australia has 16 different types of Powers of Attorney. We provide all of them online. We are arguably the only law firm in Australia to do so for all eight Australian jurisdictions: NSW, VIC, QLD, WA, SA, TAS, ACT & NT.

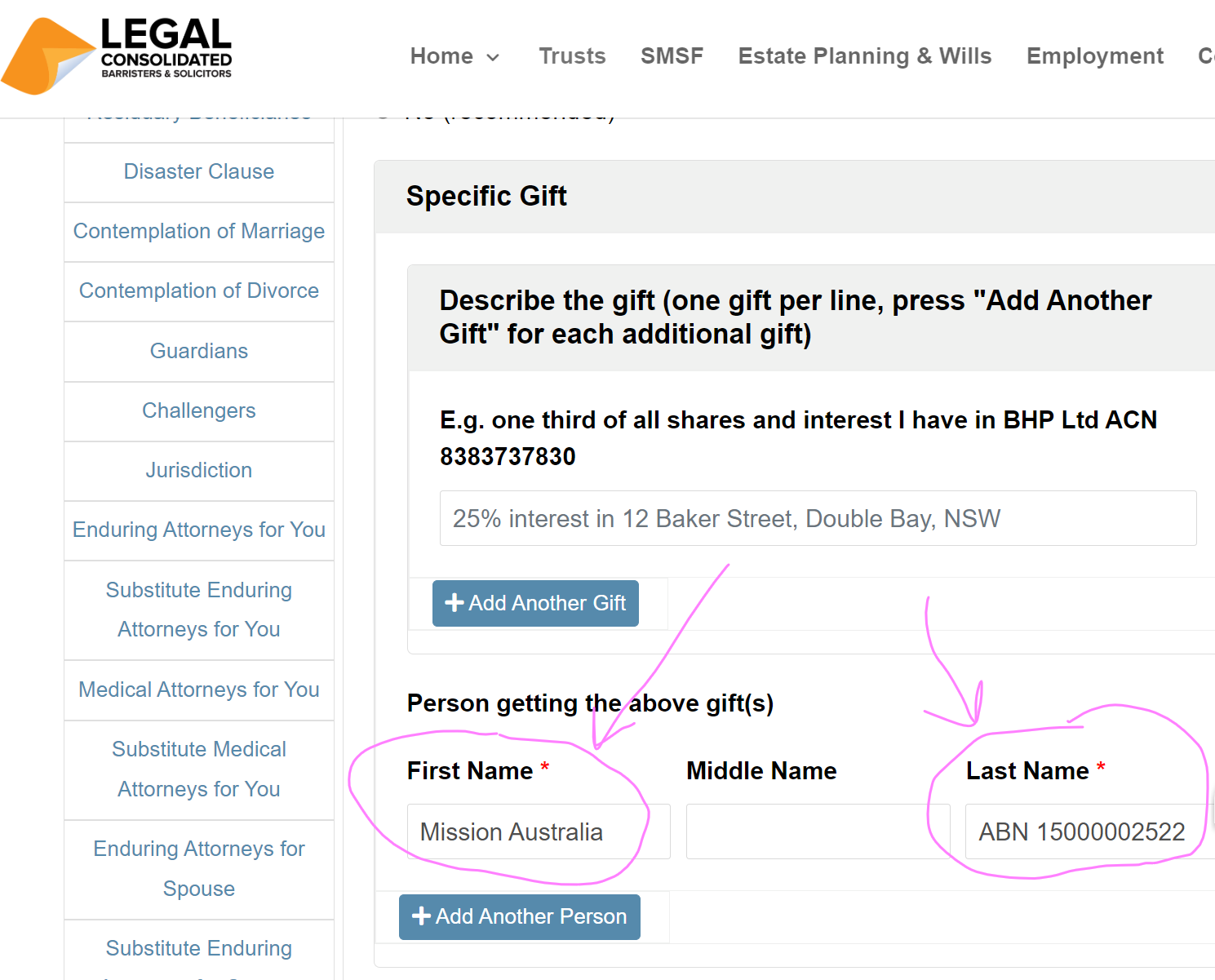

Government departments and other institutions lack the time to interpret your unique clauses. This resembles the confusion of Specific Gift clauses in a Will. They reject documents that require time to interpret, particularly if they do not see them every day.

We constantly receive feedback on best practices. This feedback comes from professionals nationwide, from a local bank manager in Wagga Wagga to a nursing home on the Gold Coast.

Do not insert clauses that, for example, permit your attorney to pay their personal debts from your funds. Such clauses may sound like a sensible precaution. However, these ‘silly powers’ render your entire Power of Attorney useless. We build our reputation on providing clear, concise and practical legal documents. The 16 types of Powers of Attorney on our website are the culmination of years of feedback. This feedback comes from the accountants, financial planners and lawyers on the front lines. They see the consequences of poorly drafted documents every day. Build a Power of Attorney that works. Do not build one that creates problems for your family when you lose mental capacity.

The Recommended Approach in preparing a POA

Not just from Legal Consolidated, but the overwhelming legal advice is that the best way to protect yourself is not by writing complex rules, but by choosing the right people. Your primary safeguard is appointing attorneys you trust implicitly to act in your best interests.

Instead of adding restrictive or increased power clauses, the better strategy is to:

- Choose Wisely: Appoint people with integrity and good judgment whom you trust completely. This is your number one protection.

- Appoint More Than One Attorney: Appointing two or more attorneys to act “jointly” for major decisions can provide a check and balance, but this has its own practical downsides (e.g., they both must sign everything).

- Have an Open Conversation: Talk to your chosen attorneys about your wishes, values, and how you would like your affairs managed. While not legally binding in the document, this guidance is invaluable for them when they need to make decisions on your behalf.

Examples of additional clauses in an Enduring POA

We have seen the damage caused by additional, or what one bank manager called “exotic” drafting. Here are the common failed examples.

1. Diluting the “Best Interests” Duty

The law requires your attorney to act in your best interests. Banks and tribunals are vigilant for instances when POAs attempt to circumvent this.

Some POAs replace attempts to usurp this duty with vague language such as ‘the best interests of the family’ or, worse still, on a non-law firm website: ‘the best interests of loved ones’. That is dangerous. It confuses the obligation and invites disputes.

We acted in matters where such exotic wording caused immediate rejection by a bank. Families were left without access to funds at the worst possible time. Senior Counsel ultimately confirmed that the wording was invalid. The EPOA failed.

It is easy, but fatal, to write exotic clauses into your POA. These are clauses we have seen rejected by the banks:

“In exercising powers under this Enduring Power of Attorney, my attorney may act in the best interests of my family.”

or

“My attorney may make decisions in the best interests of my loved ones, even if those decisions are not in my own best interests.”

These types of clauses are precisely what banks, title offices and tribunals flag as unacceptable. It conflicts with the core legal obligation that an attorney must act in the principal’s best interests.

2. Authorising Conflicts of Interest

It is common to appoint a spouse or children as an attorney. Naturally, conflicts arise — for example, paying a joint mortgage. The law already provides safeguards for these situations.

It is essential not to attempt to add clauses that pre-authorise conflicts of interest. This is reckless. It opens the door to abuse and increases the chance of challenge by other beneficiaries.

We have seen disputes where family members accused an attorney of self-dealing, relying on such exotic clauses. The matter was a risk of being referred to the Police.

Instead, rely on established legal principles that reduce scrutiny, not experimental wording.

Here are examples of failed attempts to circumvent the obligation to avoid conflicts:

“My attorney may enter into, and give effect to, any transaction notwithstanding that my attorney has a conflict of interest in the transaction, including where my attorney stands to benefit personally or where the transaction benefits my family members.”

and

“I expressly authorise my attorney to deal with my property and finances even where this creates a conflict of interest with their personal affairs or with the interests of other beneficiaries.”

These clauses attempt to give the attorney advance permission to self-deal. Banks, title offices and courts treat them with suspicion. They trigger scrutiny, increase the risk of rejection, and can invite police or civil investigation if misused.

3. Special authorisations to access information

We also see people innocently insert a special authorisation to access information clause. This is unnecessary as the power is inherent. Here are examples of failed clauses we have seen in POAs:

“My attorney is authorised to obtain and access all of my personal, medical, financial and government information, notwithstanding any privacy laws to the contrary.”

or

“I specifically authorise my attorney to request and receive information from banks, accountants, financial planners, government agencies, superannuation funds and medical practitioners, and I waive any right to privacy that would prevent disclosure.”

Instead of helping, the exotic wording creates red flags for institutions and invites unnecessary rejection.

4. Giving the attorney access to your Will

These are examples of bad drafting we have seen in failed POAs that insert an “attorney access to Will” clause into a Power of Attorney (again, this is dangerous and unnecessary wording):

“My attorney is authorised to access, inspect and obtain copies of any Will or codicil made by me, whether held by my solicitor, accountant or any other custodian.”

or

“I direct that my attorney may review the contents of my Will during my lifetime in order to manage my financial affairs consistently with my estate planning.”

5. Giving the POA an express right to sign a binding supernnuation nomination form

Here are examples of failed wording for “superannuation management powers” in a Power of Attorney:

“My attorney is authorised to make, revoke or vary any binding death benefit nomination with my superannuation fund on my behalf.”

or

“My attorney may manage, transfer or direct the distribution of my superannuation benefits, including determining who will receive those benefits upon my death.”

These types of clauses are highly problematic as the law is undecided as to whether a POA can renew a 3-year or non-lapsing Death Benefit Binding Nomination. Trying to add it to a POA adds more confusion.

6. The Home Sale That Blocked a Better Life

- The Clause: An elderly lady included a clause in her Enduring Power of Attorney preventing the sale of her home unless two doctors certified she could no longer live there safely.

- The Situation: While not mentally, her physical health was still good, but she was suffering from profound loneliness and wanted to move into a high-quality aged care facility to be with her friends. The facility required a $750,000 Refundable Accommodation Deposit, which could only be funded by selling her home.

- How it Failed: Because the lady could technically still live at home safely, her attorney (her son) could not get the required doctors’ certificates. The clause, designed to protect her, trapped her in a situation she no longer wanted. She was prevented from using her own money to improve her quality of life, and the desired spot in the facility was given to someone else.

7. The Impossible Condition

- The Clause: A woman’s Power of Attorney mandated that her attorney must get written advice from her lifelong accountant before making any investment decisions.

- The Situation: The attorney needed to reinvest a large term deposit that had matured. However, had died.

- How it Failed: The condition became impossible to meet. The attorney was forced to engage lawyers to apply to the court for an order to bypass the clause.

8. The Gift That Sparked a Family Feud

- The Clause: An attorney was authorised to give a $200 gift to each of the principal’s grandchildren on their birthday each year.

- The Situation: The principal had six grandchildren. One was estranged and living overseas, while another was struggling financially.

- How it Failed: The attorney decided not to send the gift to the estranged grandchild, leading to accusations of favouritism and a breach of the document’s instructions. The grandchild who was struggling demanded the money in cash, but the attorney wanted to buy a practical gift instead. The small, seemingly simple clause created a rift in the family, turning a gesture of kindness into a source of resentment and suspicion that tainted the attorney’s relationship with their relatives.

Exotic clauses in POAs make the POA harder to use

The more exotic the wording, the more likely the EPOA will be rejected. We have seen:

-

Landgate refusing a POA because of unusual conflict clauses, forcing the family to obtain legal opinions.

-

Banks rejecting documents that strayed from the standard duty of “best interests”.

-

Clients spending thousands fixing exotic drafting errors with barristers and tribunals.

Legal Consolidated’s approach: No Restriction, No Delay

Your Power of Attorney is not a place for ‘creative drafting’. Its purpose is practical: to work, immediately and without fuss.

That is why our EPOAs are:

-

No restriction – legally correct wording that covers the full scope of powers

-

Bank and titles office friendly – drafted for maximum acceptance

-

Court-tested – built to align with established principles, not experiments

- Free advice on how they work to both you and your family

When your family needs access to your finances, the last thing they need is a rejected document. By building your Power of Attorney with Legal Consolidated, you gain clarity, security, and the highest chance of success.

Legal Consolidated is one of the few law firms providing POAs in all of Australia’s eight jurisdictions. If adding additional clauses to POAs would protect our clients, then we would have done so. We do not do so because they cause the POAs to be rejected.

Every Australian state and territory has its own unique rules for its own Enduring POA

Every Australian state and territory has its own unique rules for its Enduring Power of Attorney (EPOA), governed by specific legislation that prescribes forms, capacity requirements, and execution formalities.

These rules aim to ensure that EPOAs are clear, legally valid, and readily accepted by third parties such as banks, land registries, and aged care facilities.

While some jurisdictions (e.g., Queensland and Victoria) allow limited tailoring for specific purposes like gifting or conflict transactions, adding non-standard or complex clauses carries significant risks across all states and territories.

We see rejection by third parties, ambiguity leading to disputes, and potential invalidity if clauses conflict with statutory duties or form requirements. Legal Consolidated’s wording is intentionally straightforward to minimise ambiguity and ensure quick acceptance.

Adding additional wording shifts the burden of validity, often requiring costly tribunal or court intervention.

Australia-Wide Considerations

Third parties, such as banks and land registries, rely on prescribed or approved EPOA forms and standard wording to ensure compliance with state legislation. Documents that do not “substantially comply” or introduce novel conditions risk rejection or delay, as institutions may require verification of compliance, pushing the matter to tribunals or courts to prove validity.

For example, the NSW Land Registry Services (LRS) explicitly states that forms must substantially comply with the prescribed form and use prescribed expressions, or they may be refused. This is a common theme across jurisdictions, as non-standard clauses can complicate transactions, especially for property dealings or financial management, leading to delays or refusals.

State and Territory-Specific Rules and Risks

New South Wales (NSW) – Strict Adherence to Prescribed Forms

- Governing Act: Powers of Attorney Act 2003 (NSW).

- Key Sections on Forms and Clauses:

- Section 19: An EPOA must be in or to the effect of the prescribed form in Schedule 2 of the Powers of Attorney Regulation 2016. The form includes a section (Clause 4) for limited conditions or limitations, but the NSW Land Registry Services warns that bespoke wording is a frequent reason for requisitions or refusal.

- Section 36(4)(e): Requires a witness to certify that the principal understands the EPOA’s effect, emphasising formal compliance.

- Risks of Adding Clauses: The Law Society advises that adding conditions, such as time limits or asset-specific restrictions, can hinder the attorney’s ability to act, as third parties (e.g., banks) may require proof that conditions are met. Deviations from the prescribed form increase the likelihood of rejection by institutions like the NSW LRS, which prioritises “prescribed expressions” for clarity.

- Bottom Line: Avoid creative clauses in NSW. Use Legal Consolidated’s prescribed form and standard wording to minimise requisitions and ensure acceptance by third parties.

Western Australia (WA) – Rigid Statutory Form Requirements

- Governing Act: Guardianship and Administration Act 1990 (WA).

- Key Sections on Forms and Clauses:

- Section 104: An EPOA must be in the prescribed form or a form to the like effect, as outlined in Schedule 3 of the Guardianship and Administration Regulations 2005. The form includes a small box for conditions or restrictions, but deviations are discouraged.

- Section 107: Attorneys must act in the principal’s best interests; custom clauses must not contradict this duty.

- Risks of Adding Clauses: The government recommends keeping the POA straightforward, warning that departures create acceptance issues with banks and Landgate (WA’s titles office), which is known for rejecting, in the words of one assessor, ‘strange-looking’ documents. Complex clauses may also prompt State Administrative Tribunal (SAT) reviews to confirm validity.

- Bottom Line: Stick to the statutory form in WA as provided by Legal Consolidated. Extra conditions commonly cause lodgement or acceptance issues with institutions like Landgate.

South Australia (SA) – Prescribed Form Emphasis

- Governing Act: Powers of Attorney and Agency Act 1984 (SA).

- Key Sections on Forms and Clauses:

- Section 6: An EPOA must be in the prescribed form (Form P2, as provided by the Legal Services Commission and Land Services SA).

- Section 7: Attorneys must exercise powers honestly and diligently.

- Section 11: Prohibits self-benefit unless expressly authorised, making custom clauses risky if they allow conflicts.

- Risks of Adding Clauses: Land Services SA examines documents for compliance with legislative and Registrar-General standards, and non-compliant or homemade clauses are frequently returned for correction. For example, hybrid clauses (e.g., joint and several appointments for different matters) often fail acceptance by banks or Land Services SA due to ambiguity.

- Bottom Line: Adopt Legal Consolidated’s Form P2 with no tailoring in SA. Bespoke clauses risk lodgement refusal by Land Services SA and validity disputes in SACAT.

Queensland (QLD) – Flexible but Cautious Approach

- Governing Act: Powers of Attorney Act 1998 (QLD).

- Key Sections on Forms and Clauses:

- Section 32: Defines EPOAs and allows specification of commencement (e.g., upon incapacity) or limitations, such as gifting to relations (Schedule 2, Section 3 excludes special personal matters).

- Section 44: Prescribes short (Form 2) and long (Form 3) forms, which include space for conditions like restricting sales or requiring unanimous decisions.

- Section 73: Attorneys may only enter conflict transactions if expressly authorised by the EPOA or a tribunal/court, making precise drafting critical.

- Section 87: Presumes undue influence in transactions benefiting the attorney or associates, placing a reverse onus on the attorney to prove legitimacy.

- Section 109A: QCAT can declare invalidity or remove attorneys if clauses cause breaches.

- Risks of Adding Clauses: Queensland’s forms allow tailored clauses (e.g., for gifts or investment philosophies), but these often lead to challenges under Sections 73 and 87. We have also seen restrictive clauses paralysing decision-making, requiring QCAT intervention.

- Cases: Re Narumon Pty Ltd [2018] QSC 185 involved an EPOA where the court allowed attorneys to extend an existing binding death benefit nomination but not create a new one due to conflict and scope issues under Section 73. This demonstrates the court’s strict interpretation of EPOA wording, particularly for conflict transactions. (Available at: http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdoc/au/cases/qld/QSC/2018/185.html)

- Bottom Line: Queensland permits tailored clauses, but they should be avoided or risk rejection and litigation.

Victoria (VIC) – Flexible but usually rejected by banks

- Governing Act: Powers of Attorney Act 2014 (VIC).

- Key Sections on Forms and Clauses:

- Section 23: Allows principals to include conditions, instructions, or limitations (e.g., gifting, conflict transactions, or reporting requirements).

- Section 64: Permits authorisation for attorney remuneration.

- Section 66: Allows authorisation for reasonable gifts or donations.

- Section 77: Requires attorneys to act in the principal’s best interests; clauses not aligning with this duty often invalidate the POA.

- Risks of Adding Clauses: The Office of the Public Advocate encourages specific instructions but warns that ambiguous or overly broad clauses may lead to VCAT scrutiny or third-party hesitation. For example, gift clauses must mirror statutory language to avoid being read down.

- Bottom Line: Tailoring is possible in Victoria, but clauses usually increase disputes and third-party rejection.

The ‘joint appointment’ POA trap that paralyses your POA

While the focus of this article is on “exotic” added clauses, a critical drafting failure often happens with the standard choices on the POA itself. This is the “joint” vs. “jointly and severally” decision.

When you appoint more than one attorney on your financial Enduring Power of Attorney, you must decide how they will act.

- Jointly: All attorneys must act together, unanimously. They must all sign every document.

- Jointly and Severally: They can act together, or they can act separately (severally).

While “jointly” may sound safer, it is a common trap. In our experience, it creates a rigid, impractical, and brittle document that often fails when your family needs it most.

Why ‘joint’ appointments of attorneys in POAs fail in practice

We constantly see families struggling with “joint” POAs. The perceived protection against fraud is almost always outweighed by the practical paralysis it causes.

- Practical Paralysis: A “joint” appointment means all attorneys must sign every single bank form, share transfer, or government document. What if one attorney is overseas, in a different state, or simply uncontactable for a week? Your affairs are frozen. This makes simple administration impossible.

- The Survivorship Failure: This is the most devastating flaw. If you appoint two attorneys “jointly” and one of them dies, resigns, or loses mental capacity, the entire Power of Attorney fails. The surviving, capable attorney cannot act. Your family is left with no valid POA and must make an expensive, stressful, and slow application to a State Tribunal (like VCAT or QCAT) to have a new administrator appointed.

Why ‘jointly and severally’ is the usual choice

Legal Consolidated’s POAs are built for maximum acceptance and practicality. Usually, your accountant, financial planner and lawyer will recommend appointing attorneys jointly and severally.

This appointment style provides the flexibility your family needs.

- It Works in the Real World: If one attorney is unavailable, the other can still act to pay bills or manage urgent affairs.

- It Survives Incapacity: If one attorney unfortunately dies or loses capacity, the POA continues. The remaining attorney(s) can still act.

- It Relies on Trust, Not Red Tape: The law already imposes high standards (fiduciary duties) on all attorneys, requiring them to act in your best interests and avoid conflict. A “jointly and severally” appointment rightly trusts your chosen attorneys to consult with each other on big decisions—as any sensible person would—without legally requiring them to sign every trivial piece of paper together.

Your best protection from fraud is not crippling the document; it is choosing attorneys you trust implicitly. A “jointly and severally” appointment allows those trustworthy people to do their job effectively.

Medical/lifestyle Power of Guardianships and Medical Decision Maker

While the examples above focus on financial/money POAs, the desire to add “exotic” clauses is just as common in medical/lifestyle documents.

Clients often attempt to include rigid instructions about “no life support” or “must remain at home,” believing they are providing clarity and certainty. As we have seen, these clauses do the opposite. They are often legally invalid, ambiguous, and create practical disasters for your appointed Guardian/Decision Maker.

Why we do not recommend ‘Medical Directives’

At Legal Consolidated, we do not prepare or recommend adding specific, rigid ‘medical directives’ to your Enduring Guardianship or Treatment Decision Maker documents. This is for all states and territories in Australia.

These directives are dangerous. They legally override your Guardian’s primary duty to act in your best interests.

The law requires your Guardian to make a decision based on the actual circumstances at the time, using the most current medical knowledge. A rigid directive, written years or even decades earlier, prevents this.

- Directives are rigid and often become outdated as medicine advances. A treatment you fear today may be routine and safe in 10 years.

- They create unintended consequences. A directive prevents your Guardian from choosing a “best case” option that did not exist when you wrote the clause.

Consider this: a client with a Jehovah’s Witness faith may include a directive for “no blood transfusions.” Years later, a synthetic blood product (like a saline-based volume expander) is developed that is not prohibited by their faith. A rigid “no transfusion” clause might be interpreted by a hospital to block this life-saving treatment.

By contrast, a trusted Guardian—who you have spoken with—understands your values (e.g., “I am of this faith”). They can ask the doctor, “Does this treatment conflict with our faith?” They have the flexibility to consent to the new, acceptable treatment.

Your true protection lies in two things:

- Appointing someone you trust implicitly.

- Having a detailed conversation with them about your values, wishes, and fears.

Allow them the flexibility to protect you. Do not tie their hands with “exotic” clauses that are guaranteed to be out of date when they are needed most.

The following examples of client-requested clauses show why this approach is so risky.

The danger of ‘absolute’ medical refusals in Medical Treatment Decision Maker POGs

Sadly, we have seen failed clauses like these:

“I do not permit my body to be maintained on medical life support for any reason.”

“I do not permit the administration of vaccinations of any kind.”

“I do not permit blood transfusions for any reason.”

While you have the right to refuse treatment, drafting an absolute, non-negotiable refusal is extremely high-risk. These rigid directives remove your Guardian’s ability to act in your best interests.

Why ‘reasonable expectation of recovery’ clauses fail

This is another common but unworkable clause:

“I do not permit my body to be maintained on medical life support unless there is a reasonable expectation of recovery.”

This clause is a “lawyer’s feast.” It creates immediate conflict and is legally ambiguous.

- Who decides what is “reasonable”? A 10% chance? A 50% chance?

- What does “recovery” mean? Recovery to your original health? Or recovery to a state of consciousness, but with severe disability?

Your family is forced to argue the definition of “reasonable” with the medical team, who may have a different professional opinion. This ambiguity does not provide clarity; it invites a stressful and costly application to a State Tribunal to interpret your vague wording.

The “remain at home” clause that backfires

A prevalent direction is:

“Should I become unable to care for myself, I wish to remain in my own home with the aid of necessary services…”

This is an understandable wish, but as a legally binding direction, it is a dangerous trap.

- Financial Impossibility: High-level, 24/7 in-home care can cost over $250,000 per year. This clause may legally force your Attorney to burn through your entire life savings in 1-2 years, leaving you with nothing for the rest of your care.

- Medical Impracticality: You may develop a condition (e.g., severe dementia, a need for specialised bariatric lifts) that cannot be managed safely at home, even with the assistance of visiting nurses.

- Restricts Best Interests: This clause legally prevents your Guardian and Attorney from choosing a high-quality, more affordable, or more medically appropriate aged care facility. They may be forced to apply to a Tribunal to override your own direction, arguing that it is no longer in your best interests.

This is a preference, not a legal direction. You should discuss this preference with your appointees, but do not put a rigid clause in a legal document that ties their hands.

A clause that guarantees failure: ‘pay from my super fund’

We see this clause, or a variation of it, with alarming frequency:

“Any expenses incurred for these services should be paid from my Superannuation Fund and maintained by my Guardians.”

This clause is 100% legally unworkable. It demonstrates a critical misunderstanding of three separate areas of law, and it fails.

- Wrong Person: Your Enduring Guardian has zero legal authority to access your money or deal with your super fund. Their role is in medical and lifestyle decisions. Your Financial Power of Attorney is the only person who can manage your finances.

- Wrong Document: A financial direction has no legal force inside a medical/lifestyle POG or Decision Maker.

- Superannuation Law: This is the most critical error. Your super is not a bank account. It is held in a trust, governed by complex Commonwealth law (the SIS Act). Your Attorney (let alone your Guardian) cannot simply “pay” from it. The money is locked away unless you meet a strict “condition of release,” such as permanent incapacity or retirement.

This clause is the perfect example of “exotic” drafting. It is legally void and will be flatly rejected by your superannuation fund’s trustee.

The ‘DNR’ clause is legally void in an Enduring Power of Guardianship (Treatment Maker in Victoria)

Here is a common, but completely ineffective, clause:

“Should I die either naturally or through misadventure I do not wish to be resuscitated.”

This clause is legally meaningless because your Power of Attorney dies with you.

All power held by your Attorney (for finance) and your Guardian (for medical) is extinguished at the exact moment of your death. They have no legal authority after that point.

Your Will is the only document that operates after you die, and your Executor is the person in charge.

An instruction about ‘resuscitation’—a medical decision made in the final moments before death—is confused and legally misplaced in a document that switches off at death. It creates legal confusion and will not be followed.

28% of POAs built on a government website do not work

You can see the complex nature of POAs. Furthermore, over 28% of POAs are incorrectly drafted and therefore do not function properly. About 13% of POAs prepared by lawyers do not work. So:

- Build your POA on our law firm’s website.

- We provide free advice and updates for the rest of your life.

- When the time comes, we will help your attorneys at no charge.

- Speak to your accountant and financial planner before you use a POA to purchase something. This is if the person who gave you the POA is now of unsound mind.

Protects from death duties, divorcing and bankrupt children and a 32% tax on super.

Build online with free lifetime updates:

Couples Bundle

includes 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Wills and 4 POAs

Singles Bundle

includes 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Will and 2 POAs

Death Taxes

- Australia’s four death duties

- 32% tax on superannuation to children

- Selling a dead person’s home tax-free

- HECs debt at death

- CGT on dead wife’s wedding ring

- Extra tax on Charities

Vulnerable children and spend-thrifts

- Your Will includes:

- Divorce Protection Trust if children divorce

- Bankruptcy Trusts

- Special Disability Trust (free vulnerable children in Wills Training Video)

- Guardians for under 18-year-old children

- Considered person clause to stop Will challenges

Second Marriages & Challenging Will

- Contractual Will Agreement for second marriages

- Wills for blended families

- Do Marriages and Divorce revoke my Will?

- Can my lover challenge my Will?

- Make my Will fair: hotchpot clauses v Equalisation?

What if I:

- have assets or beneficiaries overseas?

- lack mental capacity to sign my Will?

- sign my Will in hospital or isolating?

- lose my Will or my home burns down?

- have addresses changed in my Will?

- have nicknames and alias names?

- want free storage of my Wills and POAs?

- put Specific Gifts in Wills

- build my parent’s Wills?

- leave money to my pets?

- want my adviser or accountant to build the Will for me?

Assets not in your Will

- Joint tenancy assets and the family home

- Loans to children, parents or company

- Gifts and forgiving a debt before you die

- Who controls my Company at death?

- Family Trusts:

- Changing control with Backup Appointors

- losing Centrelink and winding up Family Trust

- Does my Family Trust go in my Will?

Power of Attorney

Money POAs: NSW, VIC, QLD, WA, SA, TAS, ACT & NT

Money POAs: NSW, VIC, QLD, WA, SA, TAS, ACT & NT

- be used to steal my money?

- act as trustee of my trust?

- change my Superannuation binding nomination?

- be witnessed by my financial planner witness?

- be signed if I lack mental capacity?

- Medical, Lifestyle, Guardianships, and Care Directives:

- Company POA when directors go missing, insane or die

After death

- Free Wish List to be kept with your Will

- Burial arrangements

- How to amend a Testamentary Trust after you die

- What happens to mortgages when I die?

- Family Court looks at dead Dad’s Will