ATO’s discretion to extend the 2-year period to sell a dead person’s home

CGT relief from selling the main residence more than 2 years after death

– Practical Compliance Guideline PCG 2019/5

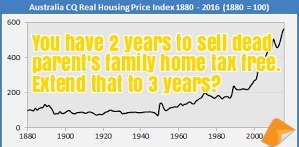

When your parents die you have two years to sell their CGT family home. (A family home is usually tax-free, but not always.)

If you sell the family home within two years of their death then you do not pay any Capital Gains Tax. For example, your parent’s principal place of residence is worth $3m when they die. You sell it 2 years later for $4m. The whole $4m is tax-free. You pocket the extra $1m with no Capital Gains Tax. That is a great windfall.

But what if you cannot sell the dead person’s home within 2 years of death? Perhaps there was an issue getting Probate. Perhaps someone is challenging the Will. Or there is a life estate or weird ‘right to reside‘.

The ATO can extend that 2-year exemption for a further 12 months. If the ATO is ‘happy’ to do so the ATO gives you a tax-free 3-year holiday. How do you get the extra 12 months?

Example of when a beneficiary gets the family home tax-free after 3 years

- At the moment of death, the Will makers’ home is worth $500k.

- After two years the family home climbs to $600k.

- If the beneficiary was able to have sold the family home within the two-year period then the extra $100k capital gain would have been tax-free. The whole $600k is tax-free.

- But there is a problem with the will, and the probate is delayed because it is not the executor’s fault.

- At the end of three years, the executor is able to work through the roadblocks, get probate and administer the estate.

- After three years the family home is worth $750k. The beneficiary directs the executor to sell the Will maker’s family home for $750k.

- There is no tax on the capital gain of $250k ($100k + $150k). (The $500k is, of course, always tax-free. Well almost always.)

How do I get the third year of CGT growth for free on a dead person’s family home?

Normally, you make a formal application to the ATO. You ask the ATO to exercise its discretion. But a formal application is expensive and time-consuming for both you and the ATO.

ATO allows you to self-assess the two-year family home discretion

On 22 August 2018, the ATO issued Draft Practical Compliance Guideline PCG 2018/D6. It is on the Commissioner’s discretion to extend the 2-year period. This is for disposing of an inherited dwelling. This is to qualify for the CGT main residence exemption. It is a partial or a full 12-month extension.

The ATO allows the taxpayer to self-assess. You make the decision whether you are eligible for the additional 12 months of tax-free growth. But you need to follow the ATO’s rules. You need to be within the ‘safe harbour’.

The draft guideline sets out what the ATO considers before it allows the 3-year discretion. It uses a ‘safe harbour’ approach. This is so you can manage your own tax affairs. This is without the ATO actually exercising the discretion itself. It saves you from having to formally apply to the ATO for the extra 12 months.

Draft Practical Compliance Guideline PCG 2018/D6

What PCG 2018/D6 about:

1. Section 118-1951 Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 disregards certain capital gains and capital losses. This is when arising from a CGT event happening to a dwelling that was a deceased person’s main residence and not being used to produce assessable income just before they died or was acquired by the deceased before 20 September 1985.

2. If you dispose of an interest in a dwelling that passed to you as an individual beneficiary or the trustee of the deceased’s estate within two years of the deceased’s death, any capital gain or loss you make on the disposal is disregarded. However, the ATO Commissioner can allow a longer period.

3. This draft Guideline outlines the factors the ATO considers when deciding whether to exercise the discretion to allow a longer period.

4. This draft Guideline also outlines a safe harbour compliance approach. It allows you to manage your tax affairs as if the ATO had exercised the discretion to allow you a longer period.

How to satisfy the ‘safe harbour’ 2 years CGT free to sell a dead person’s family home

You, as the executor or as a beneficiary of the dead person, must satisfy 5 conditions. This is before you qualify for the safe harbour protections.

1. Favourable factors to the exercise of the ATO’s discretion to sell a dead person’s family home tax-free in three years

During the 2-year period from the date of death over 12 months you spent addressing at least one of:

- challenge to the principal place of residence’s ownership

- the Will is challenged;

- a life estate (or other equitable interest) in the Will delays the disposal;

- administering the estate is delayed due to the complexity;

- settlement of the contract of sale of the dwelling is delayed or falls through for reasons outside of the taxpayer’s control.

2. The family home is listed for sale as soon as the above circumstances are fixed

The dead person’s principal place of residence is listed for sale. This is as soon as practically possible after those circumstances are resolved. Plus the sale is actively managed to completion.

3. The sale of the family home is settled within 6 months of the listing

4. Adverse factors – ‘useless excuses’ to selling your dead parents’ family home

These factors are adverse to the exercise of the ATO’s discretion. They are immaterial to the delay in selling your interest in the dead person’s home. These factors do no help you. They are useless excuses:

- waiting for the property market to pick up;

- refurbishment delays to improve the sale price;

- inconvenience on the part of the executor or beneficiary to organise the sale; or

- unexplained periods of inactivity by the executor in administering the estate.

At Legal Consolidated Barristers & Solicitors we are not sure why the ATO decided to make the ‘adverse’ factors a condition. They are not a condition. They are just irrelevant excuses.

5. Only one 12-month extension is added to your standard 2-year CGT period to sell the principal place of residence

You get 2 years to sell the dead person’s family home. That is automatic. This extension is only an extra 12 months on top of that. For example, say the Will takes 3 1/2 years to be challenged in Court. On the day of the Court case decision, you sell the home. Too late. It is over 3 years.

Does the ATO check the 3-year extension to sell the family home?

What happens if you use the safe harbour but are later audited by the ATO? The draft states that the ATO “seeks to ensure that you satisfy the relevant conditions including checking that the additional period is no longer than 12 months”. The ATO will not seek to determine whether the Commissioner’s discretion would have actually been exercised. This approach is beneficial to the taxpayer.

Hint: Keep records supporting your claim that you qualify for the safe harbour.

Examples of selling a dead person’s interest in a family home in 3 years

The draft guideline includes 7 examples. They cover:

* life interests

* family members living (swatting) in the home

* renovations due to storm damage

* subdivisions

* illness

* Will challenges

These are the examples taken straight from the ATO’s Practical Compliance Guideline PCG 2018/D6

Example 1 – safe harbour – life interest in the dead person’s family home

18. Mr Bishop acquired a dwelling before 20 September 1985. He died on 22 March 2014 and his will gave a life tenancy to his wife. Title to the property remained in the estate of Mr Bishop. Mr Bishop’s two adult children from a previous marriage are the beneficiaries of his estate.

19. Mrs Bishop continued to live in the dwelling until she died on 18 November 2016.

20. The trustee had the property cleaned and placed on the market as soon as practically possible after Mrs Bishop died. A contract for the sale of the property was signed on 11 February 2017 and settlement occurred on 14 March 2017.

21. Because the delay in disposing of the property was caused by the life tenancy (circumstances described as a favourable factor), and the property was marketed and sold as soon as was practical after the death of Mrs Bishop, the trustee could rely on the safe harbour (provided no materially adverse factors were present).

[Legal Consolidated’s comments: This is a remarkable and favourable position for the remainder persons. We, however, still do not like ‘Life Estates’ and ‘Rights to Reside’. See here.]

Example 2 – no safe harbour – family member residing in the dead person’s family home

22. When she died on 1 September 2013, Ms Evans lived with Bevan (her son and full-time carer) in her main residence. The dwelling was acquired after 20 September 1985 and was not being used to produce assessable income.

23. On the basis the dwelling would still be sold within a two-year period, the trustee of the estate allowed Bevan to continue to live in the dwelling until he found full-time employment.

24. In June 2016, Bevan obtained full-time employment and moved out of the dwelling. The trustee then sold the dwelling.

25. Because of the delay in selling the dwelling was not caused by any of the circumstances described as favourable factors, the trustee cannot rely on the safe harbour. The decision to allow Bevan to reside in the dwelling was a matter of choice within the control of the trustee.

[Legal Consolidated comment: This is an excellent example of the exemption only applying for a further 12 months. What if Bevan found full-time employment after 4 years? The exemption is lost.]

Example 3 – no safe harbour – storm damage and renovations to the dead person’s family home

26. Mr Wong lived in a dwelling that was his main residence when he died on 1 January 2016. Mr Wong acquired the dwelling before 20 September 1985.

27. On 14 July 2016, a severe storm damaged the dwelling, which required repairs before it could be advertised for sale. As well as completing repairs, the trustee also engaged builders to undertake other significant renovations to improve the value of the dwelling before the sale. Work was completed on 18 May 2017.

28. The dwelling was listed for sale on 26 June 2017 and actively managed until eventually sold. Settlement occurred on 17 January 2018.

29. Although the storm damage was outside of the control of the trustee, and the property was sold shortly after the two-year period, the trustee cannot rely on the safe harbour because the most significant factor in delaying the sale was the decision to renovate the dwelling, which was entirely within the control of the trustee.

Example 4 – no safe harbour – a subdivision of land

30. Mrs Papageorgiou lived in her main residence when she died on 1 June 2015. Mrs Papageorgiou acquired the dwelling after 20 September 1985. It was not being used to produce assessable income when she died.

31. The beneficiaries of Mrs Papageorgiou’s estate (her four adult children) decided to subdivide the property to increase the sale price. A plan was submitted to Council on 30 November 2015. On 1 July 2016, the Council advised that the plan was not approved.

32. The beneficiaries appealed the decision on 22 July 2016 and attended a hearing on 12 October 2016. On 28 February 2017, the Tribunal advised that a new subdivision application should be lodged with the Council. A new application was submitted to the Council on 24 March 2017, but by 1 June 2017, the Council had not made a decision.

33. While the resolution of the subdivision application is beyond the control of the beneficiaries, they cannot rely on the safe harbour because the delay is due to the decision to subdivide, which is not necessary for the resolution of the estate or the disposal of the dwelling.

Example 5 – safe harbour – legal challenges to the deceased’s family home

34. Mr Hawke acquired a dwelling before 20 September 1985, which was his main residence until he died on 3 October 2013. Mr Hawke acquired the dwelling before 20 September 1985. Mr Hawke’s will stated that the dwelling was to pass (in equal shares) to his two adult children from his first marriage. The Will also made separate provisions for both his first and second wives.

35. Mr Hawke’s second wife, who resided in the dwelling with Mr Hawke at the time of his death, refused to vacate the property so that it could be sold by the children. After six months of failed negotiations, the children obtained a court order requiring Mr Hawke’s second wife to vacate the property.

36. At the same time, both the first and second wives commenced legal proceedings to challenge the terms of the will. The children received legal advice that they could not dispose of the dwelling until those legal challenges had been resolved. Negotiations took place between all beneficiaries, and a settlement was eventually reached, with Supreme Court orders handed down on 21 July 2015. The dwelling was to be disposed of, and the proceeds distributed between the beneficiaries in accordance with the order.

37. The dwelling was placed on the market on 1 September 2015 and sold, with settlement occurring on 16 November 2015.

38. The children could rely on the safe harbour because the delay in disposing of the property was due mainly to legal challenges to the will of the deceased (circumstances described as a favourable factor) provided the children clearly took positive steps to address these circumstances, there were no materially adverse factors adverse and no more than an additional 12 months was required.

39. The sensitivities involved in having the deceased’s second wife vacate the property may also be a relevant factor in applying the safe harbour (depending on further detail).

Example 6 – no safe harbour – inactivity

40. Ms Kahn lived in her main residence until she died on 6 May 2013. Prior to her passing, her spouse moved into the property. Her Will stated that the dwelling was to pass in equal shares to her three children.

41. After Ms Kahn’s death, her spouse continued to live in the property and the children started legal proceedings to remove Ms Kahn’s spouse from the property. The matter was settled on 8 July 2014.

42. After the matter was settled, the property remained vacant for 18 months while the children decided what to do with the property. The property was eventually put on the market in January 2016 and sold, with settlement occurring on 3 April 2016.

43. While there was a delay in disposing of the property due to the legal action to remove the deceased’s spouse from the property, the children cannot rely on the safe harbour because the dwelling was not listed for sale as soon as practically possible after those circumstances were resolved.

Example 7 – no safe harbour – serious illness of trustee a factor for discretion

44. Mr Hubbard lived in his main residence until he died on 19 September 2014. Mr Hubbard’s son, Richard, was the sole executor and beneficiary of Mr Hubbard’s will. The house was the estate’s only asset.

45. Shortly after probate was granted, Richard was diagnosed with a serious illness and spent a large period of time hospitalised. As soon as Richard’s health improved, he cleaned out the property and placed the house on the market in January 2017, with settlement occurring on 2 April 2017.

46. Because of the delay in selling the dwelling was not caused by any of the circumstances described as favourable factors, Richard could not rely on the safe harbour. However, if asked to exercise the discretion, the Commissioner would take into account the fact that Richard’s serious illness prevented him from attending to the administration of the estate for a significant period, the fact that he took steps to resolve this as soon as practically possible and the period for which he would need the discretion to be exercised is less than 12 months.

Safe harbour to sell the dead person’s family home

You can treat the ATO’s discretion as having been favourably exercised, provided each of the following conditions are met:

- During the 2-year post-death period, more than 12 months is spent addressing one or more of the following circumstances:

-

- ownership of the property or the will was challenged;

- a life or other equitable interest created by the will delayed disposal of the property;

- delays arose in completing the administration of the estate caused by the complexity of the estate or

- settlement of the sale was delayed or fell through due to reasons outside the executor’s or beneficiary’s control.

-

- The home is listed for sale as soon as practicable after the relevant circumstances are resolved and the sale is actively managed to settlement.

- The sale settled within 12 months of listing.

- The following circumstances were immaterial to the delay:

-

- waiting for the property market to improve;

- delays due to refurbishment to improve the sale price;

- inconvenience in arranging the sale or

- unexplained periods of inactivity by the executor in administering the estate.

-

The additional period for which the discretion is needed does not exceed 18 months.

Taxpayers should maintain records to support their claim that they are eligible for the safe harbour.

This safe harbour is beneficial where the estate is challenged, or questions regarding the validity of a Will (given these Court proceedings often take more than 12 months to resolve).

When is the discretion favourably exercised to sell the dead person’s family home within the 3 years?

Taxpayers who do not meet the requirements for the safe harbour may still request the ATO to exercise its discretion via a private binding ruling.

From our experience, the ATO exercises the discretion to allow longer than 2 years to cease owning the property where:

- it could not be sold and settled within 2 years due to reasons beyond the executor’s or beneficiary’s control and

- those reasons existed for a significant part of the 2 years.

The ATO takes into account the surrounding facts and circumstances.

Examples of favourable facts and circumstances include those listed above. Additional favourable facts may include:

- the sensitivity of personal circumstances of surviving relatives; and

- difficulties in locating beneficiaries to prove the will.

The ATO focuses on the cause of the delay rather than the period of the delay when deciding whether to exercise discretion. For instance, even a very short delay beyond the 2-year limit will not lead to a favourable discretion decision without any relevant circumstances. Conversely, an extended delay will not, in itself, prevent a favourable decision.

Dead people’s homes being sold after 3 years – after COVID

Practical Compliance Guideline PCG 2019/5

Practical Compliance Guideline PCG 2019/5 is now updated for a post-COVID world. The ATO expressly deals with COVID-19. The guideline sets out how the CGT main residence exemption applies when a home is sold:

- by a beneficiary or

- by the Will’s executor.

PCG 2019/5 provides rather useless and complex examples dealing with COVID.

As set out above, the idea is to allow your executors and beneficiaries time to sell or ‘dispose’ of your home while keeping its CGT tax-free status for 2 to 3 years after your death. Capital gains after your death during this period are ignored.

The ATO does not like the discretion. And this comes across with the amended PCG 2019/5.

The Practical Compliance Guideline PCG 2019/5 sets out the ATO’s safe harbour compliance approach. It allows individual beneficiaries and trustees of your estate to manage the estate tax affairs as if the ATO had exercised the discretion. This is to allow for a longer period than 2 years to sell your home that is your main residence.

What if you fail the safe harbour conditions? The PCG sets out factors the ATO considers when weighing whether or not to exercise its discretion. These include:

- the personal circumstances of the surviving relatives,

- the degree of difficulty in locating all beneficiaries required to prove the Will,

- any period the dwelling is used to produce assessable income and

- the length of time an ownership interest is held in the home.

It is important to note that the ATO considers the circumstances that have caused the disposal delay more important than the length of the delay. Any potential capital gain or loss is also not considered relevant to the exercise of discretion.

The PCG 2019/5 is now a more complex beast. Do not try this yourself at home. (Excuse the pun.) Get your accountant to help you with this.

Protects from death duties, divorcing and bankrupt children and a 32% tax on super.

Build online with free lifetime updates:

Couples Bundle

includes 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Wills and 4 POAs

Singles Bundle

includes 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Will and 2 POAs

Death Taxes

- Australia’s four death duties

- 32% tax on superannuation to children

- Selling a dead person’s home tax-free

- HECs debt at death

- CGT on dead wife’s wedding ring

- Extra tax on Charities

Vulnerable children and spend-thrifts

- Your Will includes:

- Divorce Protection Trust if children divorce

- Bankruptcy Trusts

- Special Disability Trust (free vulnerable children in Wills Training Video)

- Guardians for under 18-year-old children

- Considered person clause to stop Will challenges

Second Marriages & Challenging Will

- Contractual Will Agreement for second marriages

- Wills for blended families

- Do Marriages and Divorce revoke my Will?

- Can my lover challenge my Will?

- Make my Will fair: hotchpot clauses v Equalisation?

What if I:

- have assets or beneficiaries overseas?

- lack mental capacity to sign my Will?

- sign my Will in hospital or isolating?

- lose my Will or my home burns down?

- have addresses changed in my Will?

- have nicknames and alias names?

- want free storage of my Wills and POAs?

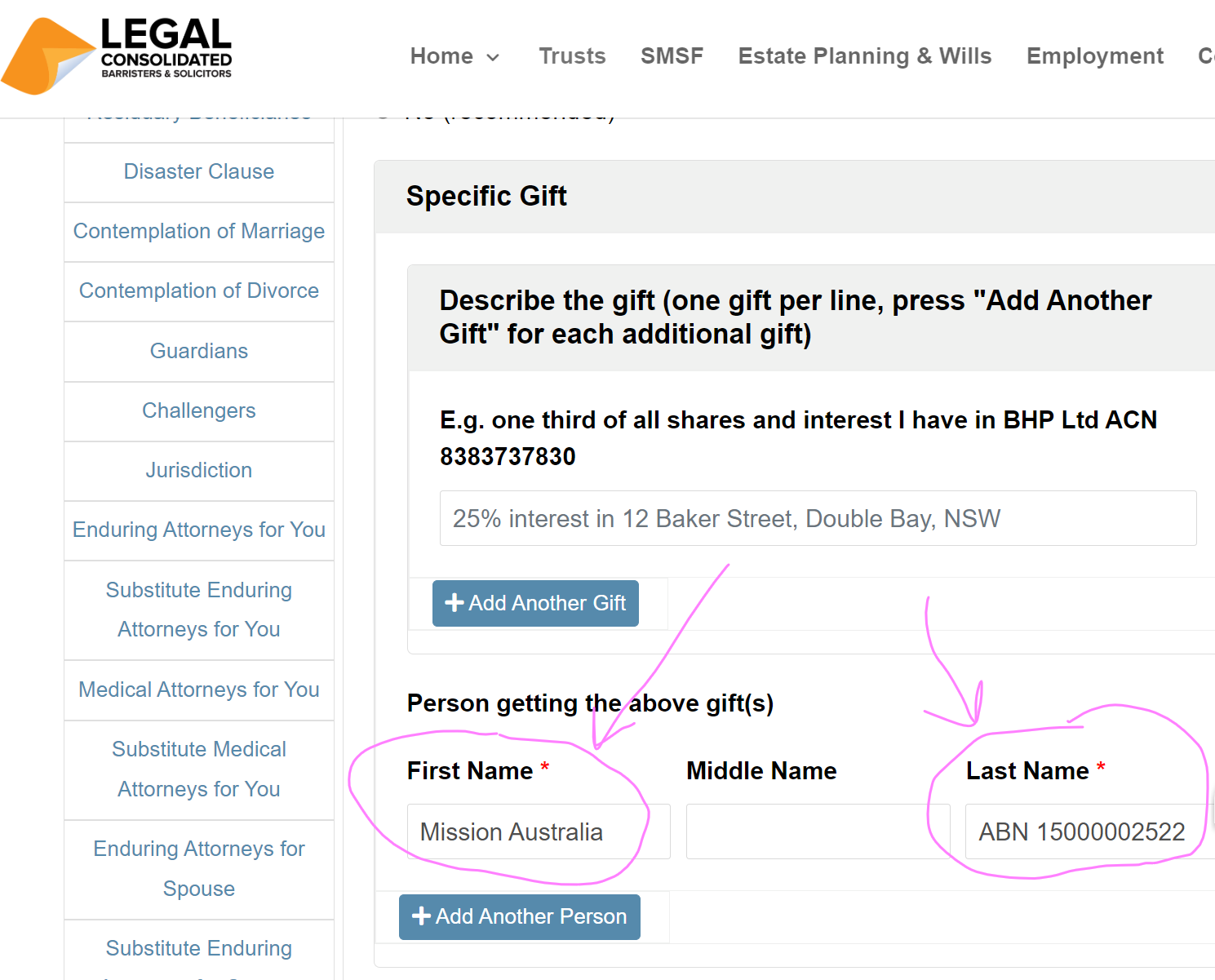

- put Specific Gifts in Wills

- build my parent’s Wills?

- leave money to my pets?

- want my adviser or accountant to build the Will for me?

Assets not in your Will

- Joint tenancy assets and the family home

- Loans to children, parents or company

- Gifts and forgiving a debt before you die

- Who controls my Company at death?

- Family Trusts:

- Changing control with Backup Appointors

- losing Centrelink and winding up Family Trust

- Does my Family Trust go in my Will?

Power of Attorney

Money POAs: NSW, VIC, QLD, WA, SA, TAS, ACT & NT

Money POAs: NSW, VIC, QLD, WA, SA, TAS, ACT & NT

- be used to steal my money?

- act as trustee of my trust?

- change my Superannuation binding nomination?

- be witnessed by my financial planner witness?

- be signed if I lack mental capacity?

- Medical, Lifestyle, Guardianships, and Care Directives:

- Company POA when directors go missing, insane or die

After death

- Free Wish List to be kept with your Will

- Burial arrangements

- How to amend a Testamentary Trust after you die

- What happens to mortgages when I die?

- Family Court looks at dead Dad’s Will