Were you of sound mind when you signed your Power of Attorney?

In the intricate web of Australian law, few legal matters carry as much significance as the capacity to create enduring powers of attorney (EPOAs) and the capacity to revoke them. These legal instruments empower individuals to name someone to manage their affairs when they cannot do so. This article delves deep into the complex terrain of mental capacity within the context of EPOAs and their revocation in Australia. While legal tests exist to determine capacity, the article aims to shed light on the practical implications of these tests and the underlying presumption of capacity that informs them.

Presumption of being of sound mind when you signed your Enduring POA

Central to understanding mental capacity in Australian EPOAs is the presumption that every adult possesses the inherent capacity to engage in legal transactions. This presumption recognises our intrinsic ability to make decisions unless evidence suggests otherwise. However, this presumption is not rigid; it adapts to the specific circumstances of each case.

The test of mental capacity when signing a POA or Power of Guardianship

In New South Wales, South Australia, and Western Australia, the tests for the capacity to create EPOAs come from legal cases. These tests pivot on an individual’s ability to grasp the nature and implications of the transaction they are entering into.

Gibbons v Wright

Echoing the sentiments of Dixon CJ, Kitto, and Taylor JJ in the landmark case of Gibbons v Wright [1954] HCA 17 91 CLR 423, mental capacity involves understanding the basic parts of a transaction when they are explained—a practical grasp of comprehension. This is like understanding the key details of a journey before embarking on it.

The Significance of Specificity and Granularity in mental capacity when signing POAs

The Significance of Specificity and Granularity in mental capacity when signing POAs

Further delving into these tests, we uncover the crucial importance of understanding the finer details. Ranclaud v Cabban (1988) NSW Conv R 55-385 amplifies this point by setting out the contours of understanding required for a valid EPOA. It’s not merely about granting authority to another person; it involves a comprehensive understanding of the myriad actions an attorney can undertake on one’s behalf. From managing financial transactions to orchestrating property sales, the individual must grasp the full spectrum of possibilities.

Justice Young in Ranclaud v Cabban stated:

Such a power permits the donee to exercise any function which the donor may lawfully authorise an attorney to do. When considering whether a person is capable of giving that sort of power one would have to be sure not only that she understood that she was authorising someone to look after her affairs but also what sort of things the attorney could do without further reference to her.

Compare this to Lord Hoffmann in Re K8 [1988] Ch 310:

Finally, I should say something about what is meant by understanding the nature and effect of power. What degree of understanding is involved? One cannot expect that the donor should have been able to pass an examination on the provisions of the Act. At the other extreme, I do not think that it would be sufficient if he realised only that it gave Cousin William power to look after his property. [Counsel as amicus curiae] helpfully summarised the matters that the donor should have understood so that he can be said to have understood the nature and effect of the power. First, (if such be the terms of the power), the attorney will be able to assume complete authority over the donor’s affairs. Secondly, (if such be the terms of the power), the attorney will in general be able to do anything with the donor’s property that he could have done. Thirdly, the authority will continue if the donor should be or become mentally incapable. Fourthly, if they should be or become mentally incapable the power will be irrevocable without confirmation by the court.

‘Mental capacity’ is not just tested on the exact moment you sign your Power of Attorney

One of the most intriguing aspects of mental capacity lies in its inherent variability over time. Various factors, such as illness, stress, or medication, can significantly impact cognitive abilities. This fluidity underscores the delicate interplay between momentary capacity and ongoing, enduring understanding. The Queensland Guardianship and Administration Tribunal’s observation in 2005 underscores the fact that capacity goes beyond a single moment of signing; it encompasses the ability to consistently make well-informed decisions over time.

Understanding the “Who” and the “What”: A Complex Appraisal

For ‘capacity’ two elements emerge the “who” and the “what.” Barrett J’s analysis in Szozda v Szozda [2010] NSWSC 804 unravels these elements. It sheds light on the importance of trustworthiness, responsibility, and the capabilities of the appointed attorney. The capacity to appoint extends beyond merely understanding the POA’s contents; it necessitates a profound comprehension of the implications of granting power and the attributes of the chosen attorney. Barrett J states:

That concept of empowering another person to act generally about one’s affairs raises two basic questions.

First, is it to my benefit and in my interests to allow another person to have control over the whole of my affairs so that they can act in those affairs in any way in which I could myself act – but with no duty to seek my permission in advance or to tell me after the event, so that they can, if they so decide, do things in my affairs that I would myself wish to do (such as pay my bills and make sure that cheques arriving in the post are put safely into the bank) and also things that I would not choose to do and would not wish to see done – sell my treasured stamp collection; stop the monthly allowance I pay to my grandson; exercise my power as appointor under the family trust and thereby change the children and grandchildren who are to be income beneficiaries; instruct my financial adviser to sell all my blue chip shares and to buy instead collateralised debt obligations in New York; have my dog put down; sell my house; buy a place for me in a nursing home?

Second, is it to my benefit and in my interests that all these things – indeed, everything that I can myself lawfully do – can be done by the particular person who is to be my attorney? Is that person trustworthy and sufficiently responsible and wise to deal prudently with my affairs and to judge when to seek assistance and advice? The decision is one in which considerations of the surrender of personal independence and considerations of trust and confidence play an overwhelmingly predominant role: am I satisfied that I want someone else to be in a position to dictate what happens at all levels of my affairs and about every item of my property and that the particular person concerned will act justly and wisely in making decisions?

This case highlighted the importance of considering the “who” in appointments. When choosing an attorney under an enduring power of attorney, people need to think about the attorney’s trustworthiness, responsibility, and ability. In this situation, Mrs Szozda’s three adult children wanted to invalidate her enduring and general power of attorney created in September 2006 when she was 95. They also sought other orders. Mrs Szozda’s daughter argued that the September 2006 power of attorney was valid and that the 2004 and March 2006 powers of attorney made by Mrs Szozda were revoked. After reviewing witness and medical evidence, Judge Barrett made factual findings about Mrs Szozda’s capacity at those times.

The capacity to sign an EPOA involves:

- a balance between understanding the instrument’s nature

- the authority it bestows

- the specific powers vested in the attorney.

When you sign you need to understand both the general concept and the intricate specifics. This equilibrium gives rise to a vivid portrait of mental capacity within the dynamic legal context.

Navigating Complexity for Ensuring Certainty

The common law, in its pursuit of safeguarding autonomy while preventing exploitation, walks a delicate tightrope. It aims to strike a balance between setting the bar high enough to deter abuse while affording individuals the opportunity to exercise their rights. The endeavour to grasp the “far-reaching ramifications” of granting power embodies this equilibrium. It ensures that an EPOA remains a tool of empowerment, safeguarding against potential entrapment.

Lambourne v Marrable: Revoking an Enduring Power of Attorney in Hospital

Mr Marrable escaped the hospital and made a new POA. Was the POA valid?

In Lambourne v Marrable [2023] QSC 219 the Queensland Supreme Court examined a challenge to the revocation and reestablishment of enduring power of attorney (EPOA) documents by Mr Harvey Marrable while he was temporarily incapacitated due to a medical condition.

Was Mr Marrable of sound mind?

Mr Marrable was hospitalised due to a blood infection that impaired his capacity and utilised a short leave from hospitalisation to revoke and update his EPOA documents. This act led to a legal examination by the Supreme Court to determine the legitimacy of his actions while deemed medically incapacitated.

The court addressed the core issue of whether Mr Marrable had the necessary cognitive ability to understand and sign the legal documents. It confirmed the legal presumption that an adult retains the capacity to manage personal and financial matters unless proven otherwise. The court emphasized that the burden of proof rests on the party claiming incapacity.

What does Lambourne v Marrable teach us?

The judgment outlined several key points:

- Capacity to make decisions can fluctuate, particularly with temporary medical conditions.

- Evidence must be presented to specifically demonstrate incapacity at the time of decision-making.

- The complexity of one’s financial affairs does not inherently demand a higher understanding to sign an EPOA.

The court upheld several principles relevant to the assessment of legal capacity:

- Individuals are presumed to have the capacity unless substantial evidence suggests otherwise.

- Decision-making ability is specific to the type and context of the decision required.

- Legal documents like EPOAs require an understanding of the nature and consequences of the document but do not necessitate a deep grasp of complex financial details.

The court noted:

“An individual’s ability to make personal health decisions does not necessarily equate to an ability to make complex financial decisions. These are distinct capacities and must be assessed as such.”

This statement reinforces the decision-specific nature of assessing capacity.

Implications for Legal and Medical Practice

The case highlights the need for:

- Rigorous assessment of capacity when individuals execute or revoke EPOAs.

- Careful consideration by medical and legal professionals of the temporary nature of certain impairments.

- Sensitivity to the autonomy of individuals in managing their affairs even when hospitalised.

Conclusion

Lambourne v Marrable is a landmark case that clarifies the conditions under which a person can revoke an EPOA during periods of temporary incapacity. It underscores the importance of recognizing the fluctuating nature of capacity and ensures that individuals’ rights are protected even in challenging health circumstances.

This case serves as a crucial reminder of the principles surrounding legal capacity and the execution of EPOAs, reinforcing the rights of individuals to control their legal and financial affairs, irrespective of temporary health setbacks.

Conclusion: A Multifaceted Tapestry Woven with Realities

As we traverse the intricacies of mental capacity within the realm of Australian EPOAs and their revocation, a vivid and multifaceted landscape emerges. It becomes abundantly clear that capacity is a nuanced concept, adapting and evolving to fit the unique contours of each case. From the foundational common law tests to the pragmatic considerations of powers and their implications, the journey toward creating an EPOA is enriched with layers of comprehension. As the legal landscape continues to evolve and cases shape the terrain, mental capacity stands as a guiding principle, ensuring that the threads of autonomy and protection weave together seamlessly, crafting a multifaceted tapestry of empowerment, assurance, and legal certainty.

Protects from death duties, divorcing and bankrupt children and a 32% tax on super.

Build online with free lifetime updates:

Couples Bundle

includes 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Wills and 4 POAs

Singles Bundle

includes 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Will and 2 POAs

Death Taxes

- Australia’s four death duties

- 32% tax on superannuation to children

- Selling a dead person’s home tax-free

- HECs debt at death

- CGT on dead wife’s wedding ring

- Extra tax on Charities

Vulnerable children and spend-thrifts

- Your Will includes:

- Divorce Protection Trust if children divorce

- Bankruptcy Trusts

- Special Disability Trust (free vulnerable children in Wills Training Video)

- Guardians for under 18-year-old children

- Considered person clause to stop Will challenges

Second Marriages & Challenging Will

- Contractual Will Agreement for second marriages

- Wills for blended families

- Do Marriages and Divorce revoke my Will?

- Can my lover challenge my Will?

- Make my Will fair: hotchpot clauses v Equalisation?

What if I:

- have assets or beneficiaries overseas?

- lack mental capacity to sign my Will?

- sign my Will in hospital or isolating?

- lose my Will or my home burns down?

- have addresses changed in my Will?

- have nicknames and alias names?

- want free storage of my Wills and POAs?

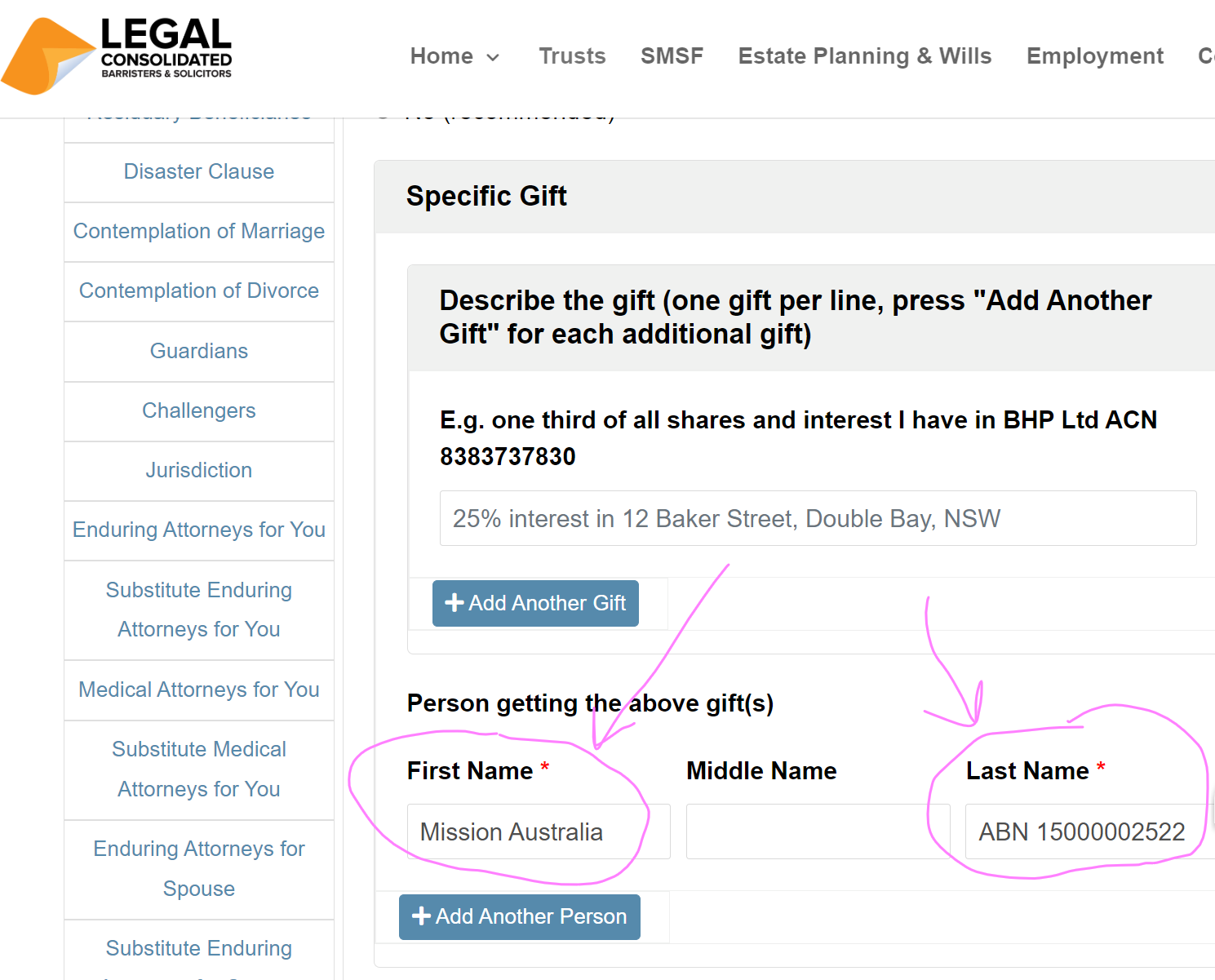

- put Specific Gifts in Wills

- build my parent’s Wills?

- leave money to my pets?

- want my adviser or accountant to build the Will for me?

Assets not in your Will

- Joint tenancy assets and the family home

- Loans to children, parents or company

- Gifts and forgiving a debt before you die

- Who controls my Company at death?

- Family Trusts:

- Changing control with Backup Appointors

- losing Centrelink and winding up Family Trust

- Does my Family Trust go in my Will?

Power of Attorney

Money POAs: NSW, VIC, QLD, WA, SA, TAS, ACT & NT

Money POAs: NSW, VIC, QLD, WA, SA, TAS, ACT & NT

- be used to steal my money?

- act as trustee of my trust?

- change my Superannuation binding nomination?

- be witnessed by my financial planner witness?

- be signed if I lack mental capacity?

- Medical, Lifestyle, Guardianships, and Care Directives:

- Company POA when directors go missing, insane or die

After death

- Free Wish List to be kept with your Will

- Burial arrangements

- How to amend a Testamentary Trust after you die

- What happens to mortgages when I die?

- Family Court looks at dead Dad’s Will