Am I sound mind enough to sign a legal document or a Will?

Do I have the mental capacity to sign a legal document?

Is it assumed I am of sound mind when signing a Will?

Yes. There is a presumption of sanity. It applies to all deeds and gifts signed by you while you are living (inter vivos).

- See:

- Attorney–General v Parnther [1792] EngR 2455; (1792) 29 ER 632, 634

- Murphy v Doman [2003] NSWCA 249; (2003) 58 NSWLR 51, 58 [36] (Handley JA, with whom Tobias JA agreed).

The law in Australia presumes every person of full age (18 years of age) can manage his or her affairs. This is until the contrary is proven.

However, where it can be shown that a deed is signed by a person who lacks mental capacity, the deed is voidable at the suit of the person affecting the transaction. See

- Ball v Mannin [1829] EngR 165; (1829) 6 ER 568, 572

- McLaughlin v Daily Telegraph Newspaper Co Ltd (No 2) [1904] HCA 51; (1904) 1 CLR 243

- Gibbons v Wright [1954] HCA 17; (1954) 91 CLR 423

Who has to prove I am of unsound mind? Who has the onus of proof to prove I am crazy?

The onus for proving a lack of mental capacity is on the person who seeks to have the deed set aside.

The standard of mental capacity required by the law for a deed is ‘issue-specific’. In other words, you work it out concerning the particular transaction contained in the contract.

As observed by the High Court in Gibbons v Wright:

The law does not prescribe any fixed standard of sanity as requisite for the validity of all transactions. It requires, in relation to each particular matter or piece of business transacted, that each party shall have such soundness of mind as to be capable of understanding the general nature of what he is doing by his participation. (page 437)

Similarly, Lindsay J. in Scott v Scott stated:

It is not, literally, a matter of imposing, or recognising, a different ‘standard’ of mental capacity in the evaluation of the validity of different transactions. What is required, rather, is an appreciation that the concept of ‘mental capacity’ must be assessed relative to the nature, terms, purpose and context of the particular transaction. Nothing more, or less, is required than a focus on whether the subject of inquiry had the capacity to do, or to refrain from doing, the particular thing under review.

Mental capacity hinges a lot on whether you understand the nature of the transaction

The requisite degree of capacity is very much part of your capacity to understand the nature of the transaction when it is explained. See:

- Gibbons v Wright (n 20) 437 (Dixon CJ, Kitto and Taylor JJ)

- A v N [2012] NSWSC 354, [389]–[391] (Ward J)

Do I have to understand everything in the Will or contract?

No. It is enough if you understand the ‘general purport’ and ‘broad operation’ of the transaction. But not necessarily its precise legal consequences. See:

- Hanna v Raoul [2018] NSWCA 201, [47]–[50] (Beazley P, with whom Macfarlan and White JJA agreed), [161] (Macfarlan JA), citing Gibbons v Wright (n 20) 438 (Dixon CJ, Kitto and Taylor JJ).

Mental incapacity unrelated to the contents of the Will may not be enough to render the Will invalid: Banks v Goodfellow (1870) LR 5 QB 549, 570–1; Bull v Fulton (1942) 66 CLR 295

The fundamental statement of the test for testamentary capacity is stated by Cockburn CJ in Banks v Goodfellow (1870) LR 5 QB 549, 565. He states:

“It is essential to the exercise of such a power that a testator shall understand the nature of the act and its effects; shall understand the extent of the property of which he is disposing; shall be able to comprehend and appreciate the claims to which he ought to give effect; and, with a view to the latter object, that no disorder of the mind shall poison his affections, pervert his sense of right, or prevent the exercise of his natural faculties — that no insane delusion shall influence his will in disposing of his property and bring about a disposal of it which, if the mind had been sound, would not have been made.”

Is my motivation or finances relevant to my mental capacity?

No. They are not. These factors are not relevant, your:

- motivation for entering into a contract

- understanding of the financial implications of doing so

- appreciation of available alternatives

These are not matters that decide on your capacity.

Ward J helps explain the appropriate enquiry into your capacity in A v N:

[T]he question as to capacity is not whether [the person signing the deed] in fact understood (though that would be of relevance when considering the allegations of undue influence or unconscionable conduct and the like) or whether he acted in a rational manner in making the decisions that he did, but whether he was capable of understanding had an appropriate explanation been given.

Debelle J in Dalle-Molle v Manos states:

[T]here are two aspects of the principle. The first is that the mental capacity is directed to the particular transaction into which the person proposes to enter. The second is that the person must have the capacity to understand the nature of that transaction when it is explained.

Can I or my family argue that the contract is not valid because I was of unsound mind at the time of signing?

Yes. You argue non est factum.

Non est factum (Latin for “it is not my deed”) is a defence. It allows you or your family to escape the performance of an agreement “which is fundamentally different from what he or she intended to execute or sign”. See Petelin v Cullen [1975] HCA 24.

A non-est factum claim means that the contract’s signature is signed by mistake. This is without your knowledge of its meaning. How could you know? You were of unsound mind at the time! Or, so your argument goes.

A successful plea makes the contract void ab initio. This is another Latin expression meaning ‘from the beginning. It is as though the contract never came into existence.

The Australian High Court in Petelin v Cullin states:[32]

The principle which underlies the extension of the plea to cases in which a defendant has actually signed the instrument on which he is sued has not proved easy of precise formulation.

The problem is that the principle must accommodate two policy considerations which pull in opposite directions: first, the injustice of holding a person to a bargain to which he has not brought a consenting mind: and, secondly, the necessity of holding a person who signs a document to that document, more particularly so as to protect innocent persons who rely on that signature when there is no reason to doubt its validity.

The importance which the law assigns to the act of signing and to the protection of innocent persons who rely upon a signature is readily discerned in the statement that the plea is one ‘which must necessarily be kept within narrow limits’ and in the qualifications attaching to the defence which are designed to achieve this objective.

But to establish a plea of non est factum, you bear the onus to produce clear and positive evidence that you are :

- under some form of disability; and

- that there is a fundamental or radical difference between the document as it was and what you believed it to be. See Saunders v Anglia Building Society [1971] AC 1004

When is an Appointor of sound mind to sign a Family Trust Deed of Variation?

Get a Doctor’s Certificate to say the person signing is of sound mind

When you build a Will or POA on Legal Consolidated’s website we direct you, in the cover letter to get a doctor’s note to say you are of sound mind.

For Wills and POAs, we require you to do this, even if you are young, leaving everything to your spouse and then your children. YOU ALWAYS NEED A DOCTOR’S CERTIFICATE.

There are special rules when you sign a Superannuation Binding Death Benefit Nomination.

Is there a single test of mental capacity in Australia?

In Australia, there is not a single legal definition of capacity. The legal understanding of capacity varies depending on the specific decision at hand. Different legal tests assess capacity, such as the ability to enter contracts, create Wills, or give instructions to an accountant, financial planner or lawyer. You can lack capacity in one aspect. But it does not mean you are lacking it in others. For example, someone might lack the capacity to manage finances but still be capable of making a Will.

Furthermore, everyone may need support in decision-making, with varying levels required depending on the decision. For example, an individual might need assistance understanding a tax return, which their accountant will need to explain, but can clearly express their will and preferences regarding a decision, like making a Will.

What tests by the accountant, financial planner and lawyer apply to capacity?

Various legal tests for capacity exist, tailored to different types of transactions. You must determine if a client comprehends the general nature of their actions. This involves understanding specific situations, evaluating consequences, reasoning through choices, and communicating consistent decisions.

To assess capacity, financial planners, accountants and lawyers may ask questions like:

- Does the client understand the relevant facts and issues?

- Are they aware of their options and obligations?

- Can they compare the likely outcomes of different choices?

- Do they recognize their decision-making abilities and limitations?

- Are they aware of potential exploitation?

- Do their conclusions align with the available information?

- Can they explain their decision-making process?

- Are their desired outcomes consistent and recallable?

These inquiries help gauge whether an individual possesses the capacity to make informed decisions.

Protects from death duties, divorcing and bankrupt children and a 32% tax on super. Build online with free lifetime updates:

Couples Bundle

includes 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Wills and 4 POAs

Singles Bundle

includes 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Will and 2 POAs

Death Taxes

- Australia’s four death duties

- 32% tax on superannuation to children

- Selling a dead person’s home tax-free

- HECs debt at death

- CGT on dead wife’s wedding ring

- Extra tax on Charities

Vulnerable children and spend-thrifts

- Your Will includes:

- Divorce Protection Trust if children divorce

- Bankruptcy Trusts

- Special Disability Trust (free vulnerable children in Wills Training Video)

- Guardians for under 18-year-old children

- Considered person clause to stop Will challenges

Second Marriages & Challenging Will

- Contractual Will Agreement for second marriages

- Wills for blended families

- Do Marriages and Divorce revoke my Will?

- Can my lover challenge my Will?

- Make my Will fair: hotchpot clauses v Equalisation?

What if I:

- have assets or beneficiaries overseas?

- lack mental capacity to sign my Will?

- sign my Will in hospital or isolating?

- lose my Will or my home burns down?

- have addresses changed in my Will?

- have nicknames and alias names?

- want free storage of my Wills and POAs?

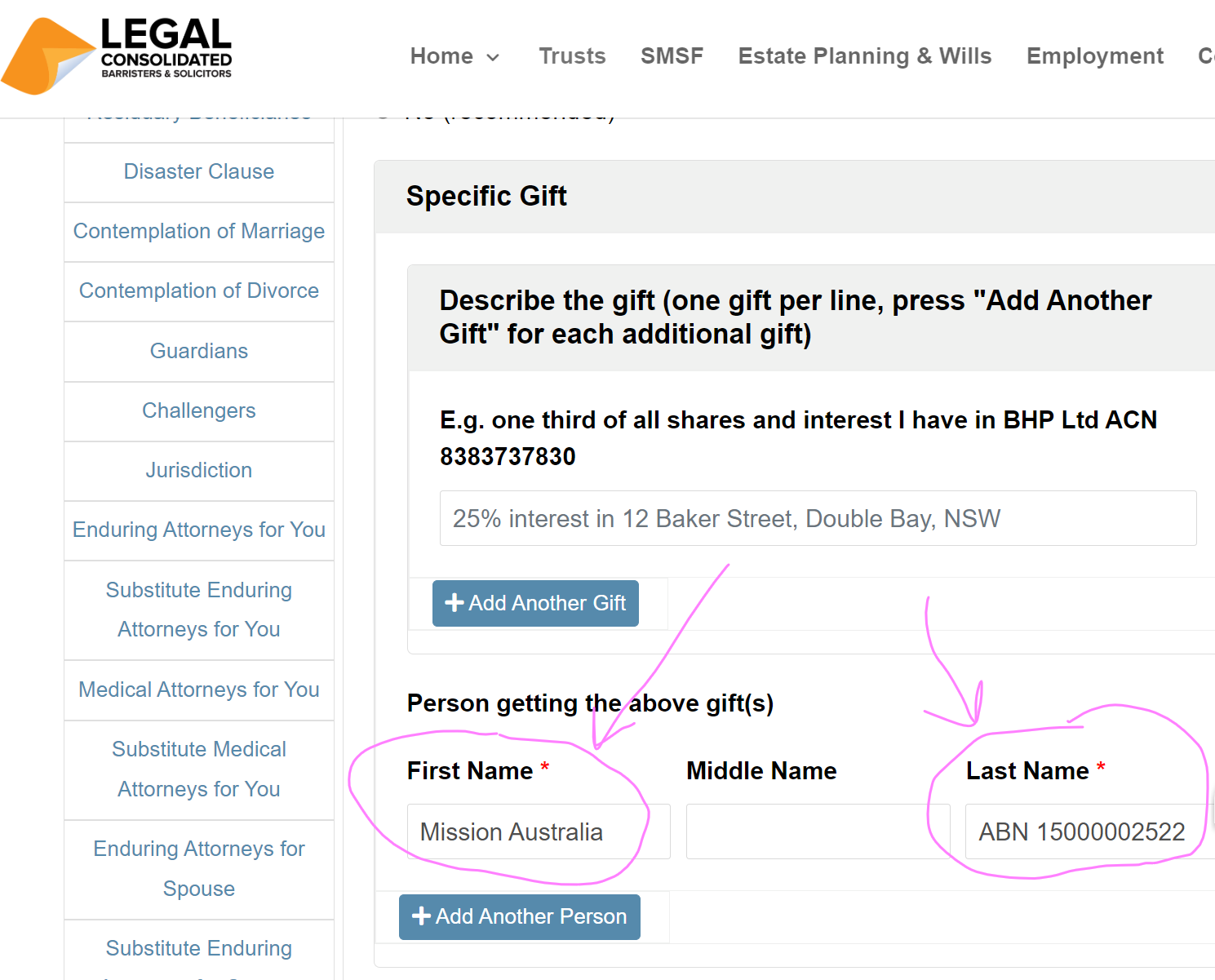

- put Specific Gifts in Wills

- build my parent’s Wills?

- leave money to my pets?

- want my adviser or accountant to build the Will for me?

Assets not in your Will

- Joint tenancy assets and the family home

- Loans to children, parents or company

- Gifts and forgiving a debt before you die

- Who controls my Company at death?

- Family Trusts:

- Changing control with Backup Appointors

- losing Centrelink and winding up Family Trust

- Does my Family Trust go in my Will?

Power of Attorney

Money POAs: NSW, VIC, QLD, WA, SA, TAS, ACT & NT

Money POAs: NSW, VIC, QLD, WA, SA, TAS, ACT & NT

- be used to steal my money?

- act as trustee of my trust?

- change my Superannuation binding nomination?

- be witnessed by my financial planner witness?

- be signed if I lack mental capacity?

- Medical, Lifestyle, Guardianships, and Care Directives:

- Company POA when directors go missing, insane or die

After death

- Free Wish List to be kept with your Will

- Burial arrangements

- How to amend a Testamentary Trust after you die

- What happens to mortgages when I die?

- Family Court looks at dead Dad’s Will