No free ride for beneficiaries buying assets out of the deceased estate: Shand v State Revenue

Beneficiaries often receive assets from a deceased estate without paying stamp duty, but is that always the case? This is especially true if they have a 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Will. Shand v Chief Commissioner of State Revenue (NSW) [2025] NSWSC 818 explores the tax consequences when a beneficiary, who is also the executor, decides to purchase an estate property.

Shand Case: A Tax Trap Exposed

In the eye-opening case of Shand v Chief Commissioner of State Revenue [2025] NSWSC 818, Hmelnitsky J unravels the tax tightrope that executors walk when purchasing estate assets, spotlighting the clash between fiduciary duties and personal gain. Without the robust shield of Legal Consolidated’s 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Will, Fiona Shand’s estate faced the full force of the Duties Act (NSW), slapping stamp duty on the entire $5,010,000 property value. This case, though rooted in NSW, sends a ripple effect nationwide, with similar stamp duty laws in other states poised to follow suit.

Do not let your estate fall into the same tax trap—Legal Consolidated’s 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Will is your fortress, expertly crafted to slash duty, safeguard wealth, and secure your legacy across three generations. Act now to outsmart the taxman and protect what matters most.

Fiona is the executor and wants to buy the home from her mum’s estate

Without the flexibility of a 3-Generation Testamentary Trust, extra stamp duty and capital gains tax apply, even if you are a beneficiary.

In Shand, Fiona Shand, the executor and a beneficiary of her mother’s deceased estate, purchased a residential property in Bondi Junction, valued at $5,010,000, at a public auction in 2023. The estate, which included this unencumbered property, was to be held on testamentary trusts for the benefit of Fiona and her three siblings, with Fiona’s trust entitled to 27.3% of the residue.

She signed a contract with herself, acting as a vendor in her capacity as executor and as a purchaser in her personal capacity. What stamp duty, if any, should Fiona pay under the Duties Act 1997 (NSW)? The usual dance ensured:

- NSW State Revenue assessed the transaction as an “agreement for the sale or transfer of dutiable property” under s 8(1)(b)(i), imposing duty on the full $5,010,000.

- Fiona objected, arguing that the transaction was a “surrender of an interest in land” by the other beneficiaries under s 8(1)(b)(iii), limiting duty to 72.7% of the property’s value (reflecting the other beneficiaries’ combined interests).

- Alternatively, if neither provision applied, the transaction fell under s 8(1)(b)(ix) as “another transaction” resulting in a change in beneficial ownership, also attracting duty on the full value.

Court’s Findings in Shand v Chief Commissioner of State Revenue

Hmelnitsky J dismissed Fiona’s appeal, upholding the assessment under s 8(1)(b)(ix), finding:

1. No Valid “Agreement” Under s 8(1)(b)(i)

The court rejected the Chief Commissioner’s contention that the contract constituted an “agreement” under s 8(1)(b)(i). Citing Minister Administering National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 v Halloran.

Hmelnitsky J noted that “a trustee cannot contractually deal with itself to sell trust property to itself in some capacity other than as trustee” (Shand at [43]). This reflects the common law “two-party rule”, which holds that a contract requires at least two distinct parties, as affirmed in:

- Clay v Clay (2001) 202 CLR 410, [51] and;

- Boensch v Pascoe (2019) 268 CLR 593, [99].

The contract, signed by Fiona in dual capacities, lacked “intrinsic validity” and was not a binding agreement for duty purposes, citing Ingram v Inland Revenue Commissioners [2000] 1 AC 293, 305D, 310G (Shand [41]).

2. No “Surrender of an Interest in Land” Under s 8(1)(b)(iii) Duties Act 1997 (NSW)

Fiona argued that the other beneficiaries’ interests in the unadministered estate were “interests in land” surrendered when she acquired the property, limiting the duty to their 72.7%. The court disagreed, holding that “interest in land” in s 8(1)(b)(iii) “includes general law concepts of beneficial ownership in land but is not limited by them”. It does not extend to the “non-specific, fluctuating interest” of a residuary beneficiary in an unadministered estate, as established in Commissioner of Stamp Duties (Qld) v Livingston (1964) 112 CLR 12, 17–18. Hmelnitsky J explained at [102]:

[The expression “interest in land”] … It is not used in a way that includes the non-specific, fluctuating interest concerning all estate assets that is commensurate with the right of a residuary beneficiary to the due administration of an estate prior to the ascertainment of the residue.

This finding in Shand aligns with long-standing precedents, such as Lord Sudeley v Attorney-General [1897] AC 11, 15 and Dr Barnardo’s Homes v Special Income Tax Commissioners [1921] 2 AC 1, 10, which establish that residuary beneficiaries have no proprietary interest in specific estate assets during administration.

3. Statutory Context: Sections 63(2) and 29(3) – A Costly Lesson in Shand

In Shand, Fiona Shand’s hopes of dodging a hefty stamp duty bill were dashed, exposing the limits of the Duties Act 1997 (NSW). Clutching at s 63(2), Fiona argued it should slash the dutiable value for her purchase of her mother’s $5,010,000 Bondi Junction property, claiming a broader “interest” to skirt unfair taxation. The court, unmoved, shut this down. Hmelnitsky J clarified at [87] that s 63(2) only applies to transfers fulfilling a beneficiary’s entitlement—not Fiona’s case, where her 27.3% residuary share stayed untouched, merely swapping the property for cash in the estate.

Fiona’s fallback to s 29(3), tied to partnership interest valuations, fared no better. The court ruled it irrelevant, designed only to prevent double taxation, not to redefine “interest” for her benefit. Without the ironclad protection of Legal Consolidated’s 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Will, Fiona’s estate was left vulnerable to the Duties Act’s full force. This ruling is a wake-up call: without strategic planning, tax traps await. Legal Consolidated’s expertly crafted trusts could have shielded Fiona’s legacy, minimising duty and securing wealth across three generations. Don’t let your estate face the same fate—choose a 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Will and outmaneuver the tax system with confidence.

4. Application of s 8(1)(b)(ix): The Tax Net Tightens

Fiona Shand’s attempt to sidestep stamp duty unravelled under the unforgiving scope of s 8(1)(b)(ix) of the Duties Act 1997 (NSW). With her transaction failing to qualify as an “agreement” or “surrender,” the court pinned it as “another transaction that results in a change in beneficial ownership of dutiable property” ([103]). This catch-all provision, as highlighted in Baxter v Chief Commissioner of State Revenue [2024] NSWCATAD 153, [53], acts like a tax net, snaring any deal that shifts ownership—like Fiona’s $5,010,000 Bondi Junction property moving from the estate to her personal hands. The result? The full ad valorum stamp duty is applied to the entire value, with no exceptions.

Had Fiona’s estate been fortified with Legal Consolidated’s 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Will, this tax sting could have been avoided. These expertly designed trusts are built to work with s 8(1)(b)(ix)’s broad reach, slashing duty and preserving wealth across three generations. Shand is a stark warning: without the right estate plan, you are at the mercy of the taxman. Secure your legacy with Legal Consolidated’s 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Will and keep your wealth where it belongs—in your family’s hands.

Legal and Practical Implications in Shand’s case

The Shand decision has implications for executors, beneficiaries, and tax professionals:

-

Executor Purchases and Fiduciary Duties:

Executors purchasing estate assets must have clear authority, such as through the will (as in Shand, where clause 15.2(r)(i)(A) permitted such transactions) or beneficiary consent, to avoid breaching fiduciary duties (Shand at [18], [105]). The court’s rejection of a valid “agreement” underscores the need for careful structuring to avoid unintended tax consequences.

-

Limited Scope of s 63(2) Duties Act 1997 (NSW):

Section 63(2) applies only when a transfer satisfies a beneficiary’s entitlement under a trust variation agreement (at [84]–[87]). This means that an executor who purchases estate assets personally without it affecting their residuary share—the exact scenario in Shand—cannot rely on s 63(2) to reduce the duty payable.

-

Broad Reach of s 8(1)(b)(ix) Duties Act 1997 (NSW):

The catch-all provision ensures that complex or novel transactions altering beneficial ownership are dutiable, protecting the revenue base (Shand [103]; Baxter v Chief Commissioner of State Revenue [2024] NSWCATAD 153, [53]). This reinforces the Duties Act’s comprehensive approach to taxation, even in estate contexts.

-

Practical Advice:

Navigating the tax minefield of deceased estates demands precision, and Shand v Chief Commissioner of State Revenue lays bare the stakes. Executors eyeing estate assets, like Fiona Shand with her mother’s Bondi Junction property, must consult tax experts before signing any contracts—stamp duty could hit the full property value, no exceptions. Securing beneficiary consent or court approval isn’t just prudent; it’s a shield against disputes and tax shocks that could unravel your plans.

Beneficiaries, take note: your stake in an unadministered estate isn’t the golden ticket you might think. The Shand ruling clarifies that it’s not a proprietary “interest in land” for duty purposes, leaving you exposed to unexpected tax liabilities. Don’t leave your legacy to chance—Legal Consolidated’s 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Wills are your secret weapon. These trusts are meticulously designed to minimise duty, protect assets across generations, and keep you ahead of the tax curve. Act smart, plan strategically, and let Legal Consolidated’s expertise secure your estate’s future.

Broader Context: Estate Planning and Tax Strategy

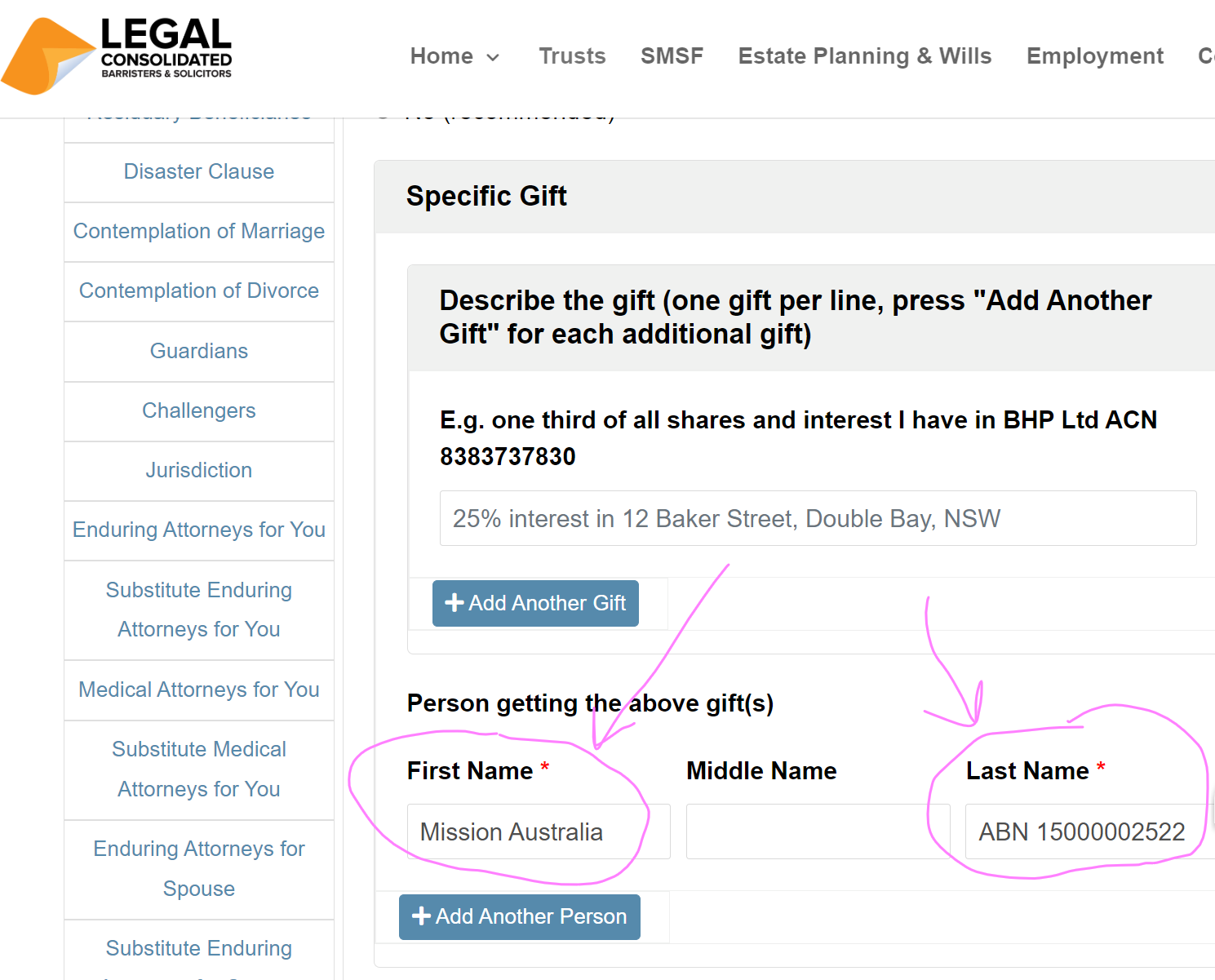

The Shand case highlights the importance of strategic estate planning to minimise duty. For example, specific gifts (e.g., giving a property directly to a beneficiary) may avoid complexities associated with residuary trusts, where non-specific interests complicate duty assessments.

Trust variations under s 63(2) can reduce dutiable value, but only with clear agreements among beneficiaries (Shand at [84]–[87]). Comparing Shand with other jurisdictions, such as Victoria’s Duties Act 2000 or Queensland’s Duties Act 2001, could reveal differences in treating residuary interests, though similar principles (e.g., Livingston) often apply (see Commissioner of State Revenue (WA) v Rojoda Pty Ltd (2020) 268 CLR 281, [57]).

Ultimately, these planning considerations must be viewed in light of the Duties Act’s overarching policy, which is to capture any change in beneficial ownership. Shand‘s reliance on the catch-all provision in s 8(1)(b)(ix) confirms this policy, ensuring that unique transactions like an executor’s purchase remain taxable to protect the revenue base.

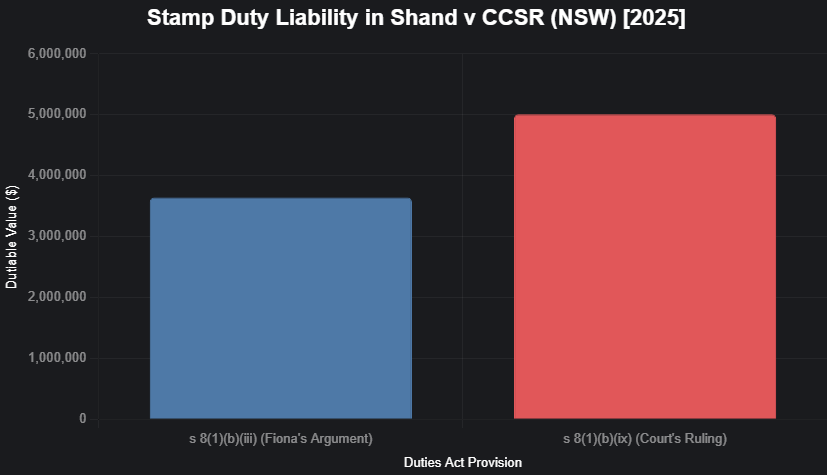

Visualising the Duty Impact

The difference in duty liability under s 8(1)(b)(iii) versus s 8(1)(b)(ix) is significant. Had Fiona succeeded, duty would have been assessed on $3,642,270 (72.7% of $5,010,000). Instead, s 8(1)(b)(ix) imposed duty on the full $5,010,000 (Shand [9]).

How to escape stamp duty when you want assets out of dead people’s estates

The Shand v Chief Commissioner of State Revenue decision is a wake-up call for executors and beneficiaries navigating the complex tax landscape of deceased estates. It cements the relentless reach of the Duties Act’s s 8(1)(b)(ix), ensuring that even well-intentioned purchases, like Fiona Shand’s acquisition of her mother’s Bondi Junction property, face stamp duty on the full value. This ruling shatters any illusion that residuary beneficiaries hold a proprietary “interest in land” during estate administration, narrowing the scope of s 8(1)(b)(iii) and s 63(2) exemptions.

For those with foresight, this case is a powerful reminder of the unparalleled protection offered by Legal Consolidated’s 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Wills. These expertly crafted trusts are designed to sidestep the tax traps exposed in Shand. By structuring your estate with precision, they empower beneficiaries to inherit assets with minimal duty exposure, while safeguarding wealth across three generations. Unlike standard wills, Legal Consolidated’s trusts offer flexibility to adapt to tax law shifts, ensuring your legacy thrives in an ever-changing legal landscape.

Executors and beneficiaries must tread carefully, armed with professional advice to balance fiduciary duties and tax obligations. Shand underscores the brilliance of proactive estate planning—why settle for costly surprises when Legal Consolidated’s 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Wills can deliver certainty, control, and tax efficiency? Secure your family’s future today with a trust that stands the test of time and tax.

Protects from death duties, divorcing and bankrupt children and a 32% tax on super. Build online with free lifetime updates:

Couples Bundle

includes 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Wills and 4 POAs

Singles Bundle

includes 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Will and 2 POAs

Death Taxes

- Australia’s four death duties

- 32% tax on superannuation to children

- Selling a dead person’s home tax-free

- HECs debt at death

- CGT on dead wife’s wedding ring

- Extra tax on Charities

Vulnerable children and spend-thrifts

- Your Will includes:

- Divorce Protection Trust if children divorce

- Bankruptcy Trusts

- Special Disability Trust (free vulnerable children in Wills Training Video)

- Guardians for under 18-year-old children

- Considered person clause to stop Will challenges

Second Marriages & Challenging Will

- Contractual Will Agreement for second marriages

- Wills for blended families

- Do Marriages and Divorce revoke my Will?

- Can my lover challenge my Will?

- Make my Will fair: hotchpot clauses v Equalisation?

What if I:

- have assets or beneficiaries overseas?

- lack mental capacity to sign my Will?

- sign my Will in hospital or isolating?

- lose my Will or my home burns down?

- have addresses changed in my Will?

- have nicknames and alias names?

- want free storage of my Wills and POAs?

- put Specific Gifts in Wills

- build my parent’s Wills?

- leave money to my pets?

- want my adviser or accountant to build the Will for me?

Assets not in your Will

- Joint tenancy assets and the family home

- Loans to children, parents or company

- Gifts and forgiving a debt before you die

- Who controls my Company at death?

- Family Trusts:

- Changing control with Backup Appointors

- losing Centrelink and winding up Family Trust

- Does my Family Trust go in my Will?

Power of Attorney

Money POAs: NSW, VIC, QLD, WA, SA, TAS, ACT & NT

Money POAs: NSW, VIC, QLD, WA, SA, TAS, ACT & NT

- be used to steal my money?

- act as trustee of my trust?

- change my Superannuation binding nomination?

- be witnessed by my financial planner witness?

- be signed if I lack mental capacity?

- Medical, Lifestyle, Guardianships, and Care Directives:

- Company POA when directors go missing, insane or die

After death

- Free Wish List to be kept with your Will

- Burial arrangements

- How to amend a Testamentary Trust after you die

- What happens to mortgages when I die?

- Family Court looks at dead Dad’s Will