What is a Contractual Will Agreement?

A Contractual Will Agreement is not a Will. It is a contract between two living people not to change their Wills and not to waste assets.

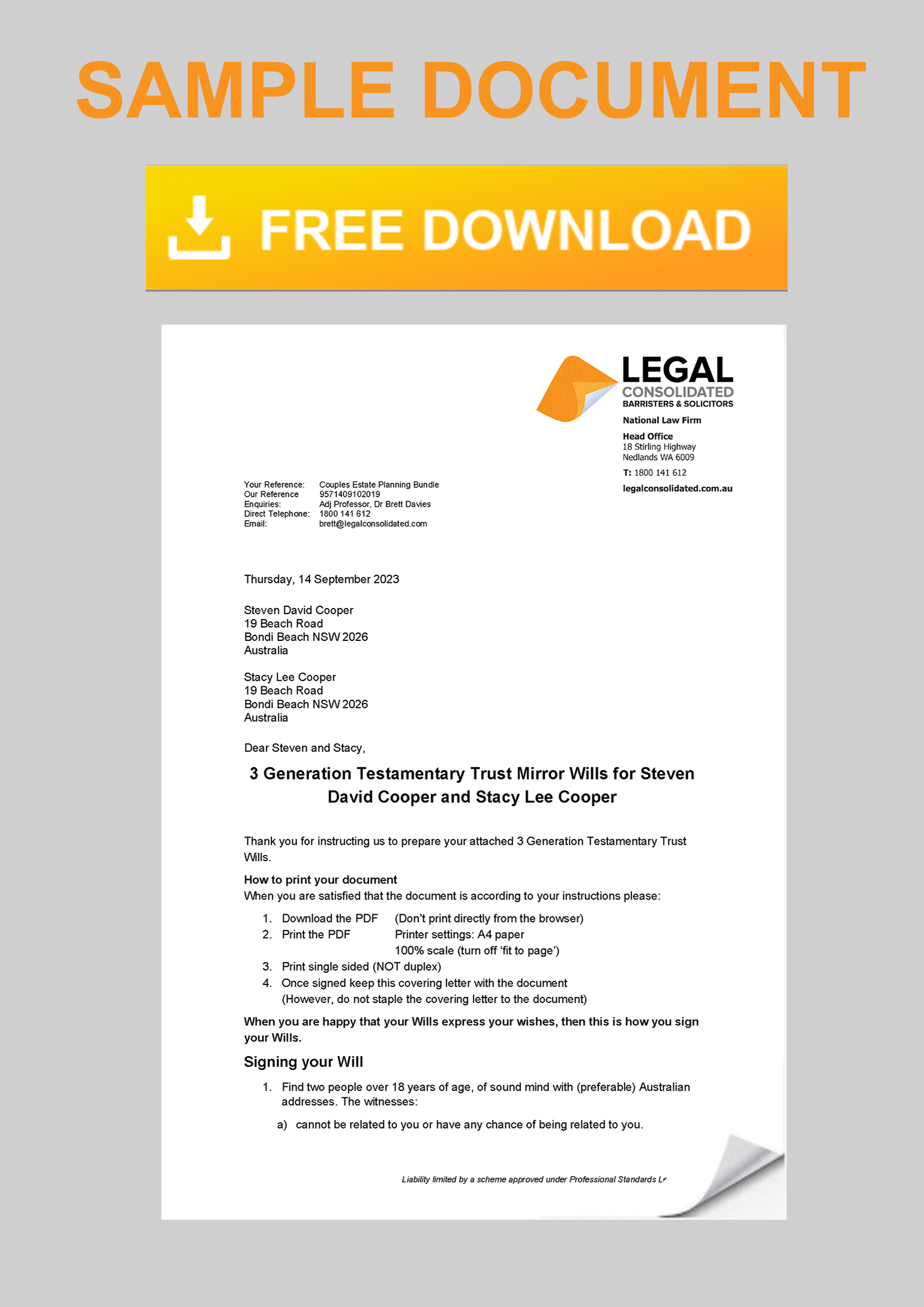

1. Example of a Contractual Agreement for Wills

Mike leaves everything in his Will to his second wife, Carol. She has her own children. When Mike dies, Carol gets everything. These are called ‘mirror‘ Wills.a

What if she cuts out Mike’s children from her Will? Mike loves his second wife. The fear of the unknown keeps him up at night. Fortunately, there is a way to put Mike’s mind at rest. Mike and Carol pressed the above START BUILDING FOR FREE. They built a Contractual Will Agreement.

They build Wills. They can be either:

- two single Wills; or

- Mirror Wills

Whoever dies last leaves half to Mike’s children and half to Carol’s children. They take extra precautions by building this Contractual Will Agreement. The Contractual Will Agreement stops them from cutting out the other children. The Contractual Will Agreement stops both of them from changing their Wills.

Mike now dies. He leaves everything to his second wife

Mike dies. Carol lived another 30 years. Mike fears that Carol will cut out his children. His fear is justified. After Mike dies Carol makes a new Will. Carol leaves everything to her own children. She leaves nothing to Mike’s children.

Mike’s children enforce the Contractual Will Agreement. The Court gives half of dead Carol’s assets to Mike’s children. Mike’s children also get back their legal costs.

2. Example of two single Wills leaving nothing to spouse – locked in by a Mutual Will Agreement

Mike leaves nothing to his second wife. He leaves everything to his children of the first relationship. Carol, his second wife does the same.

They still sign a Contractual Will Agreement. All the Contractual Will Agreement is, is just an agreement to not change the intent of your Wills. What is in the Wills is not relevant to the validity of a Contractual Will Agreement. (In this instance, the value of building the Contract Will Agreement is that it makes it harder for the last-to-die spouse to challenge your Will.)

3. Example of two single Wills leaving a bit to the second spouse – locked in by a Contractual Will Deed

- Mike leaves 25% to his new wife, Carol. The rest goes to his children.

- Carol leaves 33 1/3% to Mike, 33 1/3% to her favourite charity and the rest to her two children.

You can build a Contractual Will Agreement to lock in the intent of those two Wills. The fact that each other is not leaving everything to each other is irrelevant to the validity of a Contractual Will Agreement.

Value of an agreement to not change your Will – Can a surviving spouse change a mirror Will?

As you can see, you can ‘cut the cake’ as you see fit. Whatever your Wills state can not now be so easily challenged by your spouse, once both of you have:

- attached the two Wills to the Legal Consolidated Contractual Wills Agreement; and

- the Contractual Will Agreement is signed by both of you.

Second marriage – both are wealthy. Do you need a Contract Will

Say that the Will maker is currently married or in a de facto relationship. But they have children from a prior relationship. In this instance, their Will presents a challenge.

If they are independently wealthy, there may be no problem with each of them leaving their assets to their respective children and leaving nothing to the surviving spouse. This is because the surviving spouse has sufficient assets to provide for themselves during their lifetime.

In that case, they each build their own single 3-Generation Testamentary Trusts Will along those lines. (All to their own children.) They then attach these Wills to a Contractual Will Agreement. It is now harder to challenge the Will when the first dies.

Second marriage – both are NOT wealthy. Do you need a Contract Will Deed

However, what if your second spouse lacks sufficient wealth to live comfortably after you die? You are obliged to make proper and adequate provisions from your estate. The obligation gets greater the longer you are together.

If you fail to provide then your estate risks a family provision application in the Courts. This is where your Will is rewritten by the Court.

A Contractual Will Agreement makes it harder for your spouse to challenge your Will. A ‘Considered Person Clause‘ should also be put in your Will.

The process of building a Contractual Will agreement

- Build your two Wills, first.

- Print two copies of each of your Wills.

- One copy to sign; and

- an ‘unsigned copy‘ to attach to your Contractual Will Agreement.

- Sign your Wills, first.

- Build the Contractual Will Agreement

- The only information the Contractual Will Agreement requires is:

- your name and address

- your spouse’s name and address

- Print out the Contractual Will Agreement.

- Staple the unsigned copy of each of your Wills to the Contractual Will Agreement.

- Sign the Contractual Will Agreement.

- Scan the Contractual Will Agreement and email it to each other so that you each have a permanent copy of the agreement. (You may wish to email it to family members.)

- You each need a doctor’s certificate to confirm both of you are of sound mind. (This stops your spouse from arguing that the agreement is invalid because you are mentally insane.)

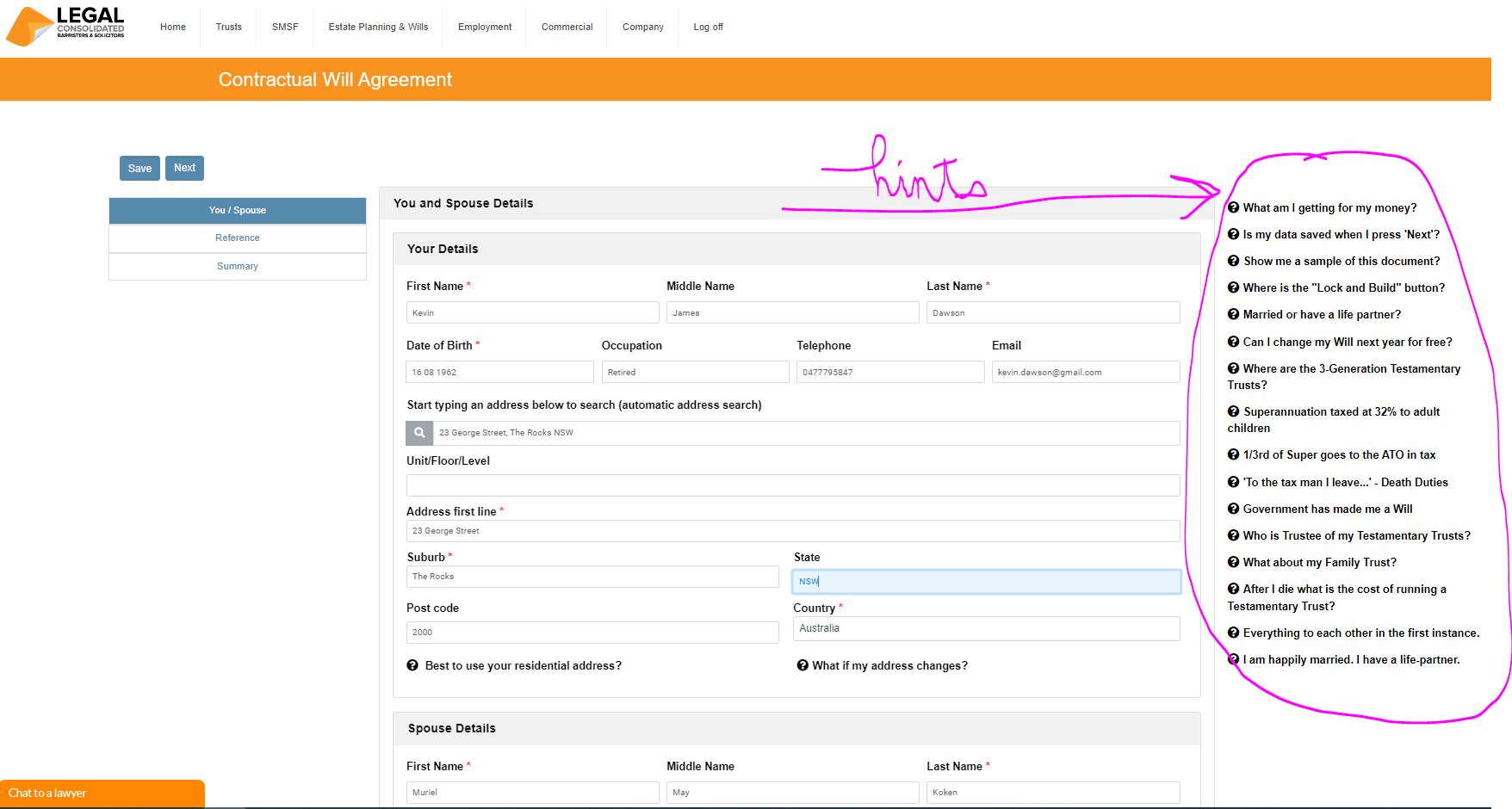

For free, start building the Contractual Will Agreement. Read the hints. Answer as many questions as you can and read the hints. The building process is designed to educate and empower you. Telephone the law firm for help answering the questions.

One child of the current Marriage. And a child from a former relationship.

Q: I have two children…

- Jake is 15 years old (previous marriage).

- Lisa is 4 months (current marriage).

If I die first, I want my 100% share to go to my current wife, Melanie. And when she dies I want Jake and Lisa to get 50% each.

But Jake is not her child. How can I make sure that Melanie ‘honours’ my wishes?

If Melanie dies first, everything goes to me. But how can my current wife Melanie be confident that upon my death, my Will continues to give half to my son Jake and the other half to our joint daughter Lisa?

A: This is the exact reason you need a Contractual Will Agreement.

It is right and proper that you leave everything to Melanie. She may need all of your wealth to live a good end-of-life experience. Quality nursing homes and the like. And the same for you. You need all of Melanie’s money to live a wonderful life with high-quality nursing and hospital support.

Mums and dads need every cent they have to get a good end-of-life experience.

In Singapore, you get 3 or 4 servants in your home for less than AUS$50k per year. In Australia, such ‘extravagance’ sets you back AUS$600k per year.

Servants and 24-hour nursing staff in your home or in a 5-star nursing home are expensive.

This is how you achieve what you want:

- Build a 3-Generation Testamentary Bundle.

- In those Wills, everything goes to each other. And when you are both dead, everything goes equally to the two children.

- And then build a Contractual Will Agreement. This stops you and your current wife, Melanie, from changing your Wills.

Why do you only ask for our names and addresses to build a Contractual Will Agreement?

Q: We are building a Contractual Will Agreement. We filled in and saved the “you and your spouse details” section. But we cannot work out where to fill in the actual details of the contract. The next step is “reference” then “summary” then “lock and build”.

A: That is correct. We do not need any more information. You are welcome to look at the full Sample. It shows in full both our cover letter and the Contractual Will Agreement. As you will see, the agreement says:

Here is my unsigned Will. Here is your unsigned Will. I agree and you agree not to change those documents.Here is my unsigned Will. Here is your unsigned Will. I agree and you agree not to change those documents.

How does a Contract Will Agreement work?

This Agreement is a document between two living people. This is often a husband and wife who each have children from prior relationships. They make Wills and want to ensure that their partner who survives them keeps their part of the bargain.

The courts honour these Agreements. For example Birmingham v Renfrew [1937] HCA 52 states:

“a contract between persons to make corresponding wills gives rise to equitable obligations when one acts on the faith of such an agreement and dies leaving his will unrevoked so that the other takes property under its dispositions.

It operates to impose upon the survivor an obligation regarded as specifically enforceable. It is true that he cannot be compelled to make and leave unrevoked a testamentary document and if he dies leaving a last will containing provisions inconsistent with his agreement it is nevertheless valid as a testamentary act. But the doctrines of equity attach the obligation to the property.

The effect is, I think, that the survivor becomes a constructive trustee and the terms of the trust are those of the will which he undertook would be his last will.”

How restricted is the surviving partner in Contract Wills?

The surviving partner can consume the assets but not give them away or waste them. They cannot act to defeat the agreement not to change the Will.

What if my partner wastes or gives away all the money?

Q: A client asks what happens if the surviving spouse sells the property after the first Will maker dies and then uses the proceeds to support a new partner.

What legal measures can prevent or address this scenario?

A: A Contractual Will Agreement is a contract. It can be enforced. If the last-to-die partner breaches the contract, then the people who are suffering can bring legal proceedings against the last-to-die partner. This is for breach of contract.

Can you sell assets under the Legal Consolidated Contractual Will Agreement?

Under a Legal Consolidated Will Agreement, assets can be sold. For example, the last-to-die Will maker can sell the property to move into a nursing home. However, wealth needs to be preserved and not wasted. Blatantly giving the sale proceeds to a new lover is a breach of the Contractual Will Agreement.

How much flexibility is there to manage the assets after I die?

Remedies for a breach of a Contractual Will Agreement

The court can then impose remedies such as financial compensation or orders to return the proceeds. If a party breaches a Contractual Will Agreement, these are the potential actions:

1. Legal Proceedings for Breach of Contract:

-

-

- Starting a Lawsuit: The aggrieved parties—typically the Residuary Beneficiaries named in the Will (often the first-to-die party’s children)—can begin legal proceedings against the person who breached the agreement. This is usually the surviving spouse or partner who acted against the terms set out in the Will.

- Court Remedies: The court can provide several remedies. These commonly include compensatory damages to cover losses caused by the breach and, in some cases, specific performance. Specific performance requires the breaching party to fulfil their obligations under the Contractual Will Agreement.

-

2. Injunctions for breach of the Last Will and Testament:

-

-

- Preventive Measures: If there is a clear risk of a breach, an injunction might be sought to prevent the breaching party from proceeding with actions that would violate the Contractual Will Agreement, such as selling a property.

-

3. Implications of the Breach:

-

-

- Impact on Estate Distribution: A breach can significantly impact how the estate is distributed among the beneficiaries. It may result in some beneficiaries receiving less than what was intended by the testator.

- Legal Costs: Legal battles over breaches in Contractual Will Agreements can be costly and time-consuming, potentially reducing the estate’s overall value left for the beneficiaries.

-

Is the Contractual Will Agreement a ‘Will’ in itself? Or is it just an agreement not to change your Will

Your Contractual Will Agreement is not a Will. You sign an agreement to say that you will not change your Will. You merely staple your and your spouse’s unsigned copies of your Wills to the back of the Legal Consolidated Contractual Will Agreement.

When does a Will become operative? When does a Contractual Will Agreement start operating?

A Will only comes into effect at the moment of your death. In contrast, your Contractual Will Agreement comes into effect when you sign it – while you are still alive.

When is it too late to cancel your Contractual Will Agreement?

A Contractual Will Agreement can no longer be rescinded once:

- one of the parties can no longer change the Will (e.g. unsound mind) or

- one of the parties die

While your partner is able to change their Will, then you notify them that you no longer want to be bound by the Contractual Will Agreement. Provided your partner has time and the ability to do so then your partner is free to make a new Will. This is without the constraints of the Contractual Will Agreement. See for example:

My partner is in a coma. Can I cancel the Contract Will Deed?

So, if your partner is in a coma, then it is too late to renounce the Contractual Wills Agreement. You are bound by it. This is because your partner does not have the ability to change their Will. This is because your partner is in a coma.

My partner has lost mental capacity. Can I cancel the Contract Will Deed?

If your partner is of unsound mind,, they cannot make a new Will. Therefore, you cannot renounce the Contractual Will Agreement.

My partner is dead. Can I cancel the Contract Will Deed?

If your partner is dead, then you obviously cannot revoke the Contractual Will Agreement. And you cannot change your Will either.

What if the last to die changes their Will in defiance of the Will Contract?

If the surviving party changes their Will following the death of the first Will maker,, they commit fraud and breach of contract. They accepted the benefit of the contract. However, they did not accept the burden attached to the contract. They broke the contract.

What happens if you change your Will in breach of the Contractual Will Agreement? The beneficiaries under the original Will (e.g. your stepchildren) bring an action against you, the surviving party. This is to enforce the Contractual Will Agreement, often through both contract law and equity.

Contractual Will Agreement v’s challenging a Will

A couple marries. They have both been married before. Each of them has two adult children. They contractually agree that in their Wills, they leave their estate to each other, and the survivor leaves his or her estate to the four children equally.

One dies, and the deceased’s children challenge the Will under the Family Provisions Legislation. Which prevails: the Contractual Will Agreement or the court challenge?

In Dillon v Public Trustee of New Zealand in 1941, the Court decided that property the subject of such a contract was available to meet an order under such legislation. However, in Schaefer v Schuhmann in 1972, the Court decided that it was not. In Barns v Barns (2003) 196 ALR 65, the High Court of Australia decided to reject Schaefer and to follow Dillon. So, challenging a Will can possibly override the Contractual Will Agreement. However, these Wills did not have a Considered Person Clause in the Wills. If they had, the outcome may have been different.

Can I have two single Wills (instead of Mirror Wills)?

Yes. You can have two single Wills or Mirror Wills—both work.

Example One – Two Single Wills: Mavis leaves everything to her children of her first relationship. Her second husband, John, is leaving everything to his child, also from his previous relationship. They build two separate single Wills to reflect that. To make it clear in both Wills they are leaving nothing to each other. They attach those two separate Wills to the Contractual Will Agreement. It is now difficult for the survivor to challenge the Will.

Example Two – Mirror Wills: By definition, mirror Wills leave everything to each other in the first instance. Ken and Muriel, after they both die, are leaving 50% to Ken’s children and the other 50% to Muriel’s children. Mirror Wills are two Wills that are mirror images of each other. They attach those mirror Wills to the Contractual Will Agreement.

We did the Wills with another law firm many years ago

That is fine. The Legal Consolidated Contractual Will Agreement is a standalone document. Legal Consolidated does not need to have prepared the Wills for the Contractual Will Agreement.

It does not matter that the Wills are signed many years apart from each other and prepared by two different law firms.

Our Wills do not leave everything to each other. Can we still lock them in with a Contractual Will Agreement?

That is fine. What is in your Wills are not relevant. They do not need to be ‘mirror’ Wills. As you correctly point out, all you are doing is agreeing not to change your Wills.

How to complete a Contractual Will Agreement

For a Contractual Will Agreement:

- Firstly, build your 3-Generation Testamentary Trust Wills:

• are you leaving everything to each other in the first instance? Build Mirror Wills here

• are you not leaving everything to each other? Build two separate single Wills here - Sign the Wills. (Stage one complete.)

- Secondly, build this Contractual Will Agreement and print out two copies.

- Staple unsigned copies of the Wills to the back of the Contractual Will Agreement.

- Sign the Contractual Will Agreement. (Stage two complete.)

- You each get a Doctor’s Certificate to confirm you are both of sound mind at the time you signed your Wills and Contractual Will Agreement

Why not attach copies of the signed Wills to the Contractual Will Agreement?

Question: Instead of the ‘unsigned’ Wills, why cannot we just make a copy of the signed Wills and staple them to the Contractual Will Agreement?

Answer: You can do that. That is equally as legal. However, there are two problems that may come about. Firstly, if you start writing with a pen on the copies of the signed Wills, it may be argued that they are now the new Wills. Secondly, people sometimes wrongly staple the actual original Will to the Contractual Will Agreement! This damages the original Wills and may render them void.) It is simpler, and there is less chance for error if you just staple unsigned copies of your Wills to the Contractual Will agreement.

What is a blended family?

A blended family for estate planning is where the Will maker or the spouse of the Will maker is involved in a previous relationship. And children are born from that previous relationship.

Our Contractual Wills Agreement works for all couples, including these blended families:

- husband and wife marry for the second (or subsequent) time:

- both have children from their first marriages, and then they have two more children

- or they do not have more children in the second relationship

- widow with children, marries for a second (or subsequent) time and has another child with her new husband

- husband and wife do not divorce and still love each other, but the husband enters into a de facto relationship and has a child outside the marriage

Our Contractual Wills Agreements also work for first relationships and de facto relationships. It is for anyone who does not want their Will is challenged by their spouse or children.

Non-spouses can also enter into Contractual Will Agreements

- Same children from same marriage: Mum leaves everything to Dad. Dad leaves everything to Mum. After they both die, they leave everything to their children

- Children from previous relationships: Mum leaves everything to Dad. Dad leaves everything to Mum. After they both die, they leave everything equally to their combined children. (Dad had children from a previous relationship. Mum had 3 children from a previous relationship. And Mum and Dad had 1 child from their own relationship. Six children in all get everything equally).

- Blended families, but one child benefits more: Mum leaves everything to Dad. Dad leaves everything to Mum. After they both die, they leave 20% to the mixed children. And 80% goes to the child of their union. They take the course of action because they believe the older children already have enough. And the younger child (of their union) needs more.

- Aunties: One sister leaves everything to the other sister. The other sister does the same. Once they are both dead, they leave 25% to their nephews and nieces and 75% to the local church.

- Same-sex with no children: They each leave everything to each other in the first instance. Once they are both dead, they leave half to each side of their family (e.g. siblings or nephews and nieces).

Can you see the pattern? They each leave everything to each other in the first instance. If you are not doing that,, you do not have ‘Mirror’ Wills. Instead, you have two single Wills.

Whether you use the expression, Mirror Wills or Mutual Wills, you need a specific agreement that the terms of the Wills are binding on the parties. And that the intent of the Wills can not be changed.

With these types of Wills, there is a lot of trust that the last to die will ‘do the right thing’ and not change the intent of the Wills. To help that ‘trust’ build and sign a Contractual Will Agreement.

Do ‘Mutual Wills’ contain an implied promise not to change the Will after the first person dies?

You may argue that ‘Mutual Wills’ contain an implied promise. But that is not guaranteed. Instead, sign a “Contractual Will Agreement” to protect the intent of the Wills.

Hussey v Bauer [2011] QCA 91 shows that Mutual Wills can, sadly, be changed after the first person dies:

“The characteristics of Mutual Wills and the means of proving their existence have been the subject of consideration in many courts. It is possible to draw from those authorities the following principles:

(a) Mutual Wills arise when two persons agree to make Wills in particular terms and agree that those Wills are irrevocable and that they will remain unaltered.

(b) Substantially similar, even identical, Wills are not Mutual Wills unless there is an agreement that they not be revoked. [Italics by Legal Consolidated.]

(c) The mere making of Wills simultaneously and the similarity of their terms are not enough taken by themselves to establish the necessary agreement.”

The case confirms that you need an inter vivos (made when you were both alive) contract. This is called a Contractual Will Agreement. It is not a Will. It is merely a contract not to change your Will. After you die (or get dementia), your partner can no longer change their Will.

How to stop your partner from changing their Will

A Contractual Will Agreement is not a Will. It is a legally binding contract between two people where:

- The makers are happy with each other Will.

- They agree not to revoke or amend their Will without the agreement of the other. Therefore, following the death of the first person (or their dementia), both Wills are irrevocable, and the intent of the Wills can no longer be changed.

The Contractual Will Agreement guarantees that property flows to the agreed and intended beneficiaries. For, say, a blended family, the surviving Will maker cannot disinherit their step-children following the death of the first spouse. For example, if half goes to your children and half goes to your stepchildren, then that is now set in concrete.

Are Contractual Wills Binding on Australian Courts?

The courts are committed to the position that a contractual arrangement with your spouse limits the right to change one’s Will. Therefore, the contractual Will agreement is:

- irrevocable; and

- binding on the other party when you die.

But where is the ‘consideration’ in a Contractual Will Agreement?

A Contractual Will Agreement is a contract. An Australian contract must satisfy several conditions, including being over 18 years of age, acting with free will, having mental capacity, etc.

Another requirement is ‘consideration’. There must be a ‘bargain’. I am giving something up to get something. You are giving something up to get something.

A Contractual Will Agreement is a mutual promise. The parties ‘give up’ the right to change their Will. They get a promise from the other for the other to also not change their Will. This is adequate consideration.

Further, to put the matter beyond doubt, Legal Consolidated structures your Contractual Will Agreement as a “Deed”. A Deed does not require consideration.

What is the ‘promise’ in a Will Contract?

A Will Contract is a contract. This is to exchange a current performance for not doing something in the future.

What is the agreement? “I promise that I will not change the intent of my Will. And you promised not to change the intent of your Will.

Do I have to leave anything to my spouse for a valid Will Contract?

No. You do not have to leave anything in your Will to the other person.

This is the ‘what’s mine is mine’. And ‘what’s yours is yours’.

This is common for a couple that keeps separate bank accounts. While many second marriages do that, it is rare for a couple of a first marriage to do so. But it does happen.

The Legal Consolidated Contract Will Agreement is designed for this scenario.

Is a Will Contract void for ‘public policy’?

What Does ‘Void for Public Policy’ Mean?

“Public policy” is society’s desire for people not to lose their rights. For example, it is your right as a defacto, mistress and child to challenge the Will. Nothing the dead person’s Will can stop you from doing that. Society gives you that right. And it cannot be unilaterally taken away from you.

A contract is void for public policy if it is deemed to conflict with the broader interests of society. Courts will not enforce contracts that encourage illegal, immoral, or unethical behaviour or those that interfere with personal freedoms. For example, agreements to commit fraud or contracts that unreasonably restrict someone’s rights are often struck down on these grounds.

When it comes to Will Contracts, the question arises: do they violate public policy? The answer depends largely on the jurisdiction.

Therefore, attempts to stop someone from challenging your Will, that are put in the actual Will, normally fail. They fail because they breach the rule of ‘public policy’.

But you can, via contract, agree not to challenge a Will. That is a big difference.

The Global View on Will Contracts

Most countries recognise Will Contracts as valid and enforceable. These agreements are treated as legally binding contracts, provided they meet the usual requirements for contract formation—such as mutual consent, consideration, and lawful purpose.

However, some jurisdictions do hold Will Contracts as void against public policy. This is often because such agreements can be seen as limiting the freedom of the Will maker to change their testamentary intentions. Critics argue that these contracts may undermine a fundamental principle of wills: the right to revoke or alter a Will at any time during the Will maker’s lifetime.

The Australian Position on Will Contracts

Australia does not consider Will Contracts void for public policy. Courts in Australia uphold these agreements when they are legally prepared by an Australian law firm such as Legal Consolidated. This means parties can rely on a Will Contract to ensure their estate is distributed according to agreed terms, even if the surviving party later changes their mind.

Does a Will Agreement have to be in writing?

We do not give advice on silliness. We do not take risks. We are a conservative taxation law firm. If you want to do something ‘clever’, you should go to another law firm.

We follow best practices for Contract Wills. This is based on Australian law. The best practice is to fully document the contract in writing.

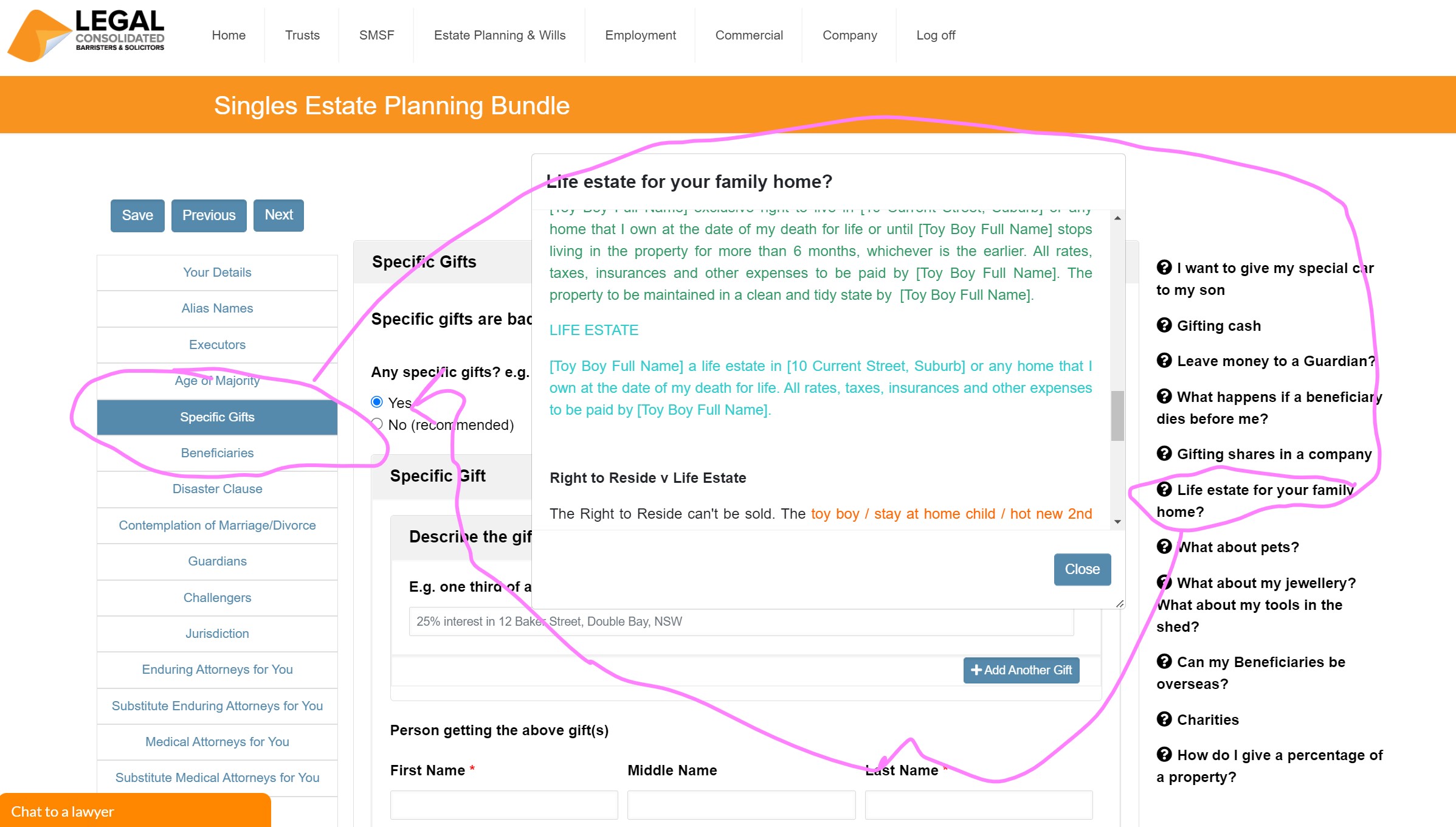

Do Contractual Will Agreements work for life estates?

Sometimes, Contractual Will Agreements are for people with different beneficiaries. In that instance, you build two separate single Wills. (In contrast, if you leave everything to each other and then everything to your children and your partner’s children, then you build Mirror Wills.)

But they may still want the last to die to be able to live in the family home until they themselves die.

You would, therefore, put a life estate in your Will. This is how to build a Will with a Life Estate.

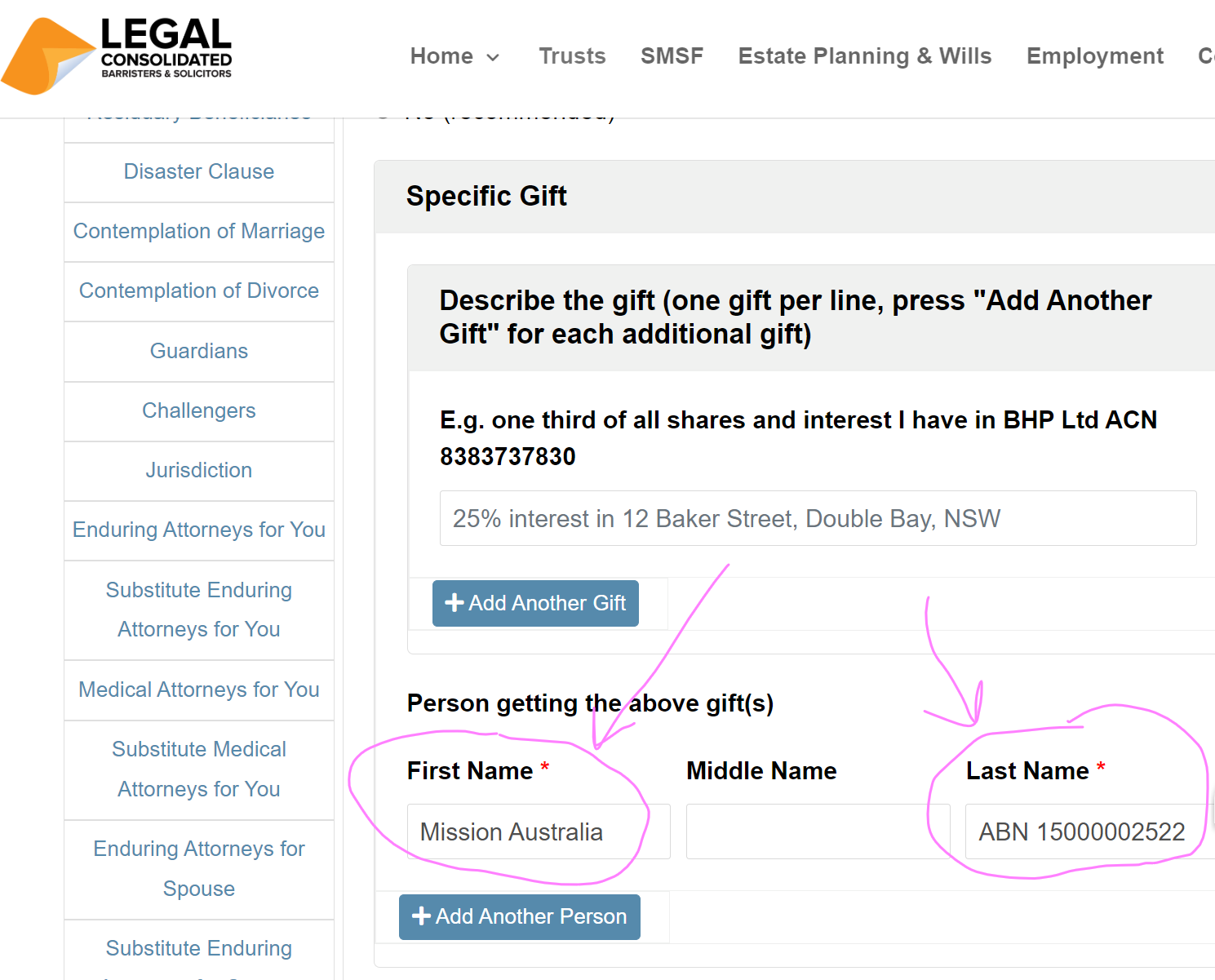

An example of this is when the husband builds a Will leaving everything to his children. But he puts a Specific Gift clause in his Will. (See the above diagram.) This allows the wife to use the asset (usually a home) until she dies. This Specific Gift is called a life estate.

The wife agrees not to challenge his Will. And, in the same Contractual Will Agreement, the husband agrees not to challenge her Will.

Can Mutual Wills or Mirror Wills themselves be contractual binding – not to change the intent of the Wills

It may come down to terminology.

As my article suggests, to ensure there is a binding agreement, you need a “Contractual Will Agreement”. This is sometimes called by other lawyers “Mutual Wills”. Either way, you need an ‘agreement’. Or an ‘understanding’ that you can not change your Will, or at least the intent of the Will.

In contrast, ‘leaving everything to each other then everything to the same people’ is not, in my view, automatically a contractual agreement. Other things would need to happen; perhaps an exchange of emails or a statement may make it a verbal contract.

As my article further states, even a Contractual Will Agreement can be annulled if one party tells the other they are no longer bound – this is provided the other party can now change their Will (i.e. has mental capacity). To your actual example, I do not think it was a contract between the Will makers. But even if it was, it would be annulled by a change of circumstances.

Example of a Contractual Will

Consider the case of Forster v Forster [2022] QSC 30.

There is a Contractual Mutual Will in place. This is where the now-dead person and the surviving spouse agreed to give each other their residuary estates. This is to allow the survivor to maintain a similar lifestyle.

The survivor is contractually bound to maintain a Will that gifts their residuary estate equally between the deceased’s children and the survivor’s children.

The applicant in the case is one of the dead person’s children. As is common, the child does not like his stepmother.

The child wants his stepmother to disclose all of her personal assets and liabilities. He wants that information every year.

The stepmother fights back against the disclosure. But agrees to the terms of the Mutual Contractual Will Agreement. She has to do this anyway, so it is no great concession on her part.

The son seeks an order under section 8 Trust Act 1973 (Qld).

Her Honour did not find a single authority that supported the son’s argument. She refuses the application. The case is set out below.

What happens if we die at the same time?

My second wife is richer than me

I sound like a broken record, but a Contractual Will Agreement is not a Will. It is simply an agreement not to change your Will without mutual consent.

If you want to give her children more, email us, and we will prepare a free voucher to update your Legal Consolidated Wills. You can then update your Mirror Wills so that, once both of you are dead—whether in the same car accident or 20 years apart—her children get, say, 75%, and your children get 25%.

Build the estate planning Mirror Will bundle here:

-

Everything to each other in the first instance.

-

Once both of you are dead, then whatever is left goes 75% to her children and 25% to your children.

Since your Wills are Mirror Wills, it does not matter who dies first or even if you die in the same car accident.

Q: Another law firm prepared our Will. Should I let them know that we have locked them in so that they can not be changed with a Contractual Will Agreement?

You are welcome to do as you wish. But there is no legal requirement to do so.

The Advantages of a Legal Consolidated Contractual Will Agreement

A Legal Consolidated Contractual Will Agreement, in compliance with Forster v Forster:

- sets out a fiduciary obligation of the utmost faith

- establishes a trust relationship

- requires disclosure of the financial position of the survivor

Mum is dead. Dad remarries. Now what?

First Marriage Contractual Wills

Q: I’m building the Estate Planning bundle (3-Generation Testamentary Trust Mutual Wills and 4 POAs) for my parents.

I accept that almost 100% of the Wills drafted in Australia leave everything to each other. And then everything to the children equally once both parents are dead.

However, I have friends burned by Mum, leaving everything to Dad. And then Dad re-partners. Dad:

- leaves everything to the new spouse or

- the ‘step mum’ challenges the Will. (I understand that Binding Financial Agreements stop working at death. And in any event, no longer work.)

How can my Mum leave everything to Dad in the first instance, and Dad guarantees that everything goes to his children and not some gold digger?

I know Contractual Will Agreements are common for second marriages. But does a Contractual Will Agreement also work for first marriages?

A: You are correct. The Contractual Will Agreement is common for second marriages. This is because Mum owes her love to two groups of people: her new husband and her own children. Her second husband also has two divided loyalties: his new wife and his own children.

But in a first marriage where there are children only of that marriage then there is no divided loyalty. Dad leaves everything to Mum. Mum leaves everything to Dad. Once they are both dead, everything goes to the children equally. I agree with you. Pretty much everyone structures their Mutual Wills that way. It is so common that our Mutual Wills only operate that way.

Contractual Will Agreements for first marriages are rarer. But they operate for any couple. There is nothing stopping your parents from building an additional document called a Contractual Will Agreement. But they need to have built their Wills first.

Can my Will say it will not be changed when my partner dies?

Verbal vs Deed of Mutual Wills

You and your spouse can verbally agree not to change your Will. This is on a handshake. Or, you could put this in your Will—however, neither works.

They are not ‘contracts’ or ‘agreements’. Nor are they ‘Deeds’.

Statements and promises in a Will are not enforceable contracts. The Will may have been put in the bin many years ago. And a new Will prepared.

You need a separate contract signed as a deed. The deed is separate from your Will. A Deed of Mutual Wills is actionable. The promises are enforceable.

Full case of Forster v Forster

The best information about Australian Contractual Will Deeds is found in the case of Forster v Forster. We have put the full case below with Legal Consolidated’s comments in orange.

Forster v Forster [2022] QSC 30

| CITATION: | Forster v Forster [2022] QSC 30 |

| PARTIES: | JAMES DERWENT CAMPBELL FORSTER (applicant) v ANNABEL LISA FORSTER (respondent) |

| FILE NO/S: | BS No 12687 of 2021 |

| DIVISION: | Trial Division |

| PROCEEDING: | Application |

| ORIGINATING COURT: | Supreme Court at Brisbane |

| DELIVERED ON: | 8 March 2022 |

| DELIVERED AT: | Brisbane |

| HEARING DATE: | 7 December 2021; final written submissions received 9 February 2022 |

| JUDGE: | Ryan J |

| ORDER: | The application is refused. I will hear the parties as to costs. |

| CATCHWORDS: | SUCCESSION – MAKING OF A WILL – TESTAMENTARY INSTRUMENTS – JOINT AND MUTUAL WILLS – where deceased and his wife had each been married before – where each had children from their previous marriage – where deceased and his wife executed a mutual wills agreement in which they agreed to execute “mutual wills”, leaving their property first to their survivor absolutely, and then, upon the survivor’s death, to their five children/step-children in equal shares – where deceased’s wife inherited most of his estate in accordance with his (mutual) will – where it is not alleged that the deceased’s wife has breached, or will breach, the terms of the mutual wills agreement – where the deceased’s wife’s step-son seeks an order requiring her to account to him for her assets during her lifetime – whether the deceased’s wife holds the property, the subject of the mutual wills agreement, as constructive trustee for her children and step-children – whether court should make an order under section 8 of the Trusts Act 1973 (Qld) requiring the deceased’s wife to disclose her financial position to her step-son on a yearly basisTrusts Act 1973 (Qld), section 8Barns v Barns and others (2003) 214 CLR 169Bauer & Ors v Hussey & Anor [2010] QSC 269Birmingham & Others v Renfrew & Others (1937) 57 CLR 666Dufour v Pereira (1769) 1 Dick 419; 21 ER 332Flocas v Carlson and others [2015] VSC 221Gordon Archibald Bigg v Queensland Trustees Limited Unreported, N0 825 of 1989Lord Walpole v. Lord Orford (1797) 3 Ves. 402Palmer v Bank of New South Wales (1975) 133 CLR 150Re Basham [1986] 1 WLR 1498Re Cleaver, decd. [1981] 1 WLR 939Re Dale (decd) [1993] 4 All ER 129Re Goodchild (deceased); Goodchild and another v Goodchild [1996] 1 All ER 670Re Hagger [1930] 2 Ch 190, cited in ‘Mutual Wills’ paperSchaefer v Schuhmann and Others (1972) 46 ALJR 82 (Privy Council |

| COUNSEL: | I Klevansky for the applicant C A Brewer for the respondent |

| SOLICITORS: | The Estate Lawyers for the applicant Holding Redlich for the respondent |

OVERVIEW [of Forster v Forster]

[1] This application arose out of a dispute over the estate of Timothy Forster (the deceased). The applicant is the deceased’s son, James. The respondent is the deceased’s widow, and James’ stepmother, Annabel.[1] Annabel was the deceased’s second wife. They had each been married once before. The deceased had three children (including James) from his first marriage. Annabel has two.

[2] In broad terms, by his will, the deceased left his estate to Annabel absolutely, having agreed with her in a “mutual wills agreement” (MWA) that, upon her death, it would be shared equally among their five children and step-children.

[3] After the deceased’s death, Annabel inherited his estate in accordance with his will, which also provided smaller gifts to his own children. In 2020, James and his siblings applied for further provision from their father’s estate, but ultimately withdrew their application.[2]

[4] James and Annabel do not have a good relationship. After his father’s death, and the administration of his estate, James, through his lawyers, has repeatedly asked Annabel to make disclosure to him of her financial position. Annabel, through her lawyers, has repeatedly stated that: (a) she will not disclose her financial position to James; (b) she is not in breach of the MWA; and (c) she will comply with her obligations under the MWA.

[5] Notwithstanding Annabel’s statements in [4] (b) and (c), James does not trust her and suspects that she has, or will, breach the MWA. I hasten to add that there was no evidence before me to support such a suspicion. Indeed, James’ lawyers confirmed[3] that they have no evidence that Annabel had, or would, breach the MWA.

[6] In the face of Annabel’s refusal to provide her financial information to him, James applied for court orders requiring her to disclose her financial position to him yearly, from now until her death, relying upon the doctrine of mutual wills, and section 8 of the Trusts Act 1973 (Qld).

[7] For James to succeed in his application, he needed to persuade me of three things, namely –

(a) that Annabel held the property the subject of the MWA (that is, the property she inherited from the deceased and her own property) on constructive trust for James during her lifetime,

and, if so,

(b) that the pre-conditions for an order under section 8 of the Trusts Act had been met including that Annabel had done an act or made an omission or decision as trustee which aggrieved James, or that there were reasonable grounds for apprehending that Annabel might do such an act or make such an omission or decision,

and, if so,

(c) that it was appropriate for me to order Annabel to account to James for the property during her lifetime.

[8] As to (a), in my view, properly understood, the authorities and the paper upon which James relied in this application do not support his assertion that Annabel is a constructive trustee of the property the subject of the MWA.

[9] Indeed, the paper upon which James relied included a quote from the judgment of McMillan J in Flocas v Carlson [2015] VSC 221 in which her Honour said (in obiter) that it was plain that property the subject of an MWA was not held on trust during the lifetime of the surviving party to an MWA. Having made that observation, I wish to stress that I am not suggesting that I considered her Honour’s view determinative of (a). As my reasons demonstrate, I studied the authorities and the paper upon which James relied in great detail and reached the conclusion that, in the absence of fraud, Annabel does not hold the property the subject of the MWA in trust for James[4] during her lifetime.

[10] As to (b), even if I am wrong about (a) and Annabel is a constructive trustee of the property the subject of the MWA, James relied only on suspicion and mistrust and fell well short of establishing reasonable grounds for apprehending that Annabel might do an “aggrieving” act or make an “aggrieving” omission or decision.

[11] As to (c), even if I am wrong about (a) and Annabel is a constructive trustee of the property the subject of the MWA, the nature and scope of the trust are defined by the MWA and the wills made in pursuance of it. In my view, Annabel’s entitlement under the MWA and the deceased’s will to absolute ownership of the property the subject of the MWA, albeit subject to certain limits set out in the MWA, is inconsistent with a requirement that she account to James for that property during her lifetime.

[12] James made a late attempt to suggest that “equity” was “engaged” and would require Annabel to account to him even if she were not a trustee because she had refused to disclose her assets and liabilities to him.[5] Apart from the fact that the application was not brought on that basis, and the respondent had no opportunity to reply to it, that suggestion is wholly unsupported in law (indeed, James made it without reference to authority or principle) and reflected a misunderstanding of equitable remedies.

[13] James’ application is refused.

[14] My reasons, in more detail, follow.

Background [of Forster v Forster]

[15] The deceased and Annabel were married for 24 years. It was a second marriage for each of them. Annabel has two children from her first marriage. The deceased had three children (including James) from his first marriage. There are no children of the marriage of the deceased and Annabel.

[16] The deceased and Annabel entered into a mutual wills agreement (MWA) on 20 August 2015, intending to achieve, after their deaths, the equal distribution of their combined estate among their five children and step-children. Paragraph C of the MWA’s recitals stated their intention –

The parties desire to make Wills each providing entirely for the other on the first of them to die but on the second of them to die to ensure that as far as possible (subject to extenuating circumstances) all five children of both of them are treated equally with regard to the residue of the Estate.

[17] Essentially, under the MWA, the survivor of the deceased and Annabel was permitted to use the estate to maintain their (I infer, high) standard of living and to pay for their necessary health and aged care; but was not permitted to intentionally “substantially diminish” it, including by making gifts to their own children. These obligations are expressed at clause 3 of the MWA as follows –

Each of the parties agrees that upon the death of the other and having inherited the Estate of the other:

(a) he or she will ensure that any Will made subsequently is generally in accord with the provisions of the Will annexed hereto in the sense that it generally provides equally for all of the children of both parties subject as in herein provided;

(b) he or she will not thereafter take any action which is intended to substantially diminish the assets which would otherwise comprise his or her Estate and would be the subject of his or her will (for example by a substantial gift or gifts to his or her own son or daughter) other than what is reasonably consistent with the maintenance of a reasonable standard of living to which the parties have been accustomed and for necessary health and aged care; and will take all reasonable precautions for the preservation of the Estate.

[18] The limits to which I referred in [11] above are those set out in clause 3(b).

[19] There was no will annexed to the MWA – or at least not in the copy of it relied upon by the applicant.

The deceased’s will [in Forster v Forster]

[20] The deceased executed his will on the same day as the MWA was made.

[21] By clause 2, the deceased appointed Annabel to be his executor and trustee.

[22] By clause 3, he left certain shares to his own three children.

[23] By clause 4, which concerned the proceeds of his life insurance policy, he gave $125,000 to one of his own daughters (explaining that he had already given $100,000 to his two other children during his lifetime); and the balance to the trustee of a trust called “The JSLF Trust” – “J” “S” and “L” being the first initials of the names of the deceased’s own children.

[24] By clause 5 of his will, he gave to Annabel –

- his household contents;

- his shares in certain trustee companies (other than the trustee company for The JSLF Trust); and

- “the rest of his estate … absolutely”.

[25] He also appointed Annabel and his lawyer as joint “Guardians, Appointors or Principals” of any discretionary trust of which he was guardian, appointor, or principal at the time of his death.

[26] Clause 6 set out what was to happen if Annabel pre-deceased the deceased. Consistently with the MWA, the clause broadly distributed the estate equally between the deceased’s three children and Annabel’s two children, including through certain trust arrangements.

[27] Clause 9 contained the following declaration –

I DECLARE that no provision is made in this Will for my son JAMIE and my daughters LUCY and SARAH (in the event that ANNABEL shall survive me), other than the provisions of clauses 3 and 4 of my Will because my Will is made as a mutual Will with the Will of ANNABEL to the intent that both ANNABEL and I will make provision in our Wills for both My Children and Annabel’s Children to take effect on the death of the survivor of us pursuant to an Agreement signed by myself and ANNABEL on this day which provides for an equal distribution of the residue of our Estates and (per stirpitally) among My Children and Annabel’s Children subject to the provisions of that Agreement to take effect on the death of both or of the survivor of us.

[28] The deceased died on 28 September 2018. In accordance with his will, Annabel inherited most of his estate. Also, as the surviving joint tenant of their $3 million matrimonial home, she assumed ownership of it.

Lead up to the present application [in Forster v Forster]

[29] There is hostility between James and Annabel.

[30] Although James has not expressly asserted that Annabel has or will substantially diminish her estate during her lifetime (including to advantage her own children over her stepchildren), this application is premised on the basis that she might – although, I emphasise, the evidence presented to me does not support such a premise.

[31] James, through his lawyers, asked Annabel to disclose “her personal assets and liabilities which are the subject of the mutual will agreement”. She, through her lawyers, declined to do so, although she promised to abide by the terms of the MWA.

[32] Against that background, James applied to the Court for orders that: (a) Annabel disclose to him her current assets and liabilities, within 14 days of the order, and on or before 30 June of each year thereafter; and (b) she provide James with 14 days’ notice of her transfer of any property worth more than $50,000.

Parties’ arguments [in Forster v Forster]

[33] James asserted that, in accordance with the doctrine of mutual wills, upon the death of his father, a constructive trust was imposed upon the property the subject of the MWA, and Annabel therefore held it as trustee for him (and, I assume, his siblings and stepsiblings), relying on certain cases and a paper by Justice Rene Le Miere of the Supreme Court of Western Australia, all of which are discussed below.

[34] James then relied upon section 8 of the Trusts Act 1973 (Qld) as the source of the Court’s power to make the orders sought, asserting that he was a person with a contingent interest in trust property, which Annabel held as a constructive trustee.

[35] Section 8 provides –

8 Application to court to review acts and decisions

(1) Any person who has, directly or indirectly, an interest, whether vested or contingent, in any trust property or who has a right of due administration in respect of any trust, and who is aggrieved by any act, omission or decision of a trustee or other person in the exercise of any power conferred by this Act or by law or by the instrument (if any) creating the trust, or who has reasonable grounds to apprehend any such act, omission or decision by which the person will be aggrieved, may apply to the court to review the act, omission or decision, or to give directions in respect of the apprehended act, omission or decision; and the court may require the trustee or other person to appear before it and to substantiate and uphold the grounds of the act, omission or decision which is being reviewed and may make such order in the premises (including such order as to costs) as the circumstances require.

(2) An order of the court under subsection (1) shall not—

(a) disturb any distribution of the trust property, made without breach of trust, before the trustee became aware of the making of the application to the court; or

(b) affect any right acquired by any person in good faith and for valuable consideration.

(3) Where any application is made under this section, the court may—

(a) if any question of fact is involved—determine that question or give directions as to the manner in which that question shall be determined; and

(b) if the court is being asked to make an order which may adversely affect the rights of any person who is not a party to the proceedings—direct that that person shall be made a party to the proceedings.

[36] Section 5 of the Act defines “trust” as follows –

trust does not include the duties incidental to an estate conveyed by way of mortgage, but with that exception trust extends to implied, resulting, bare and constructive trusts, and to cases where the trustee has a beneficial interest in the trust property, and to the duties incidental to the office of a personal representative.

[37] Section 5 of the Act defines “trust property” as including “property settled on any trust, whether express, implied, resulting, bare, or constructive”.

[38] The parties proceeded on the basis that the success of James’ application depended primarily on my finding that Annabel is the constructive trustee of a trust of which James is a beneficiary, thereby rendering section 8 applicable. That was an oversimplification of things. Even if I were to find that Annabel is a constructive trustee of the property the subject of the MWA, it does not automatically follow that it would be appropriate to require her to account to James in the way he desired.

[39] Nor did James’ submissions address in any meaningful way the pre-requisites to an order under section 8. He did not clearly identify the “act omission or decision” or the apprehended “act, omission or decision” upon which his application was based. I did not know whether he was relying upon Annabel’s “decision” not to provide her financial information to him; or (more likely) whether he was suggesting that he apprehended that she would somehow breach her obligations under the MWA.

[40] If he intended to rely upon the latter apprehension, then he did not expressly address me on the reasonable grounds upon which it was said to be based. He complained about Annabel’s refusal to disclose her financial position to him; and he asserted that she had not accurately valued the deceased’s estate. But it did not logically follow from either Annabel’s declining to provide James with details of her financial position; or the way in which she valued the deceased’s estate,[6] that she was intending to deal with her property contrary to the MWA. Nor did James’ counsel assist me to understand how it might be said that either of those matters amounted to reasonable grounds.

[41] Annabel submitted that James’ application was entirely misconceived and based on a misapprehension of the law of mutual wills and constructive trusts. She submitted that, although the MWA imposed obligations upon Annabel and the deceased, it did not “create” a trust (either at the time of the execution of the MWA or upon the death of the deceased). Annabel submitted that a constructive trust is a remedy, imposed by the Courts of Equity, to prevent fraud. That would include the fraud involved in a breach of the obligations created by the MWA; but in the absence of such a fraud, no trust existed.

[42] The evidence before me revealed that James’ lawyers told Annabel that they were “determined to force [her] to make full and complete disclosure as well as an ongoing disclosure” to ensure that the rights of James and his two siblings were protected. Obviously, it is by this application that James and his siblings hope to force Annabel to make the disclosure they seek. James submitted that, unless I granted the relief sought, if Annabel were to avoid her obligations under the MWA , he may not become aware of it in time to take any meaningful action in response.

Preliminary discussion [in Forster v Forster]

[43] Second or third (or beyond) marriages (or other unions or long-term intimate relationships)[7] are not uncommon and modern families often include a blend of the children of both spouses.[8]

[44] Spouses in second (or subsequent) marriages may wish to ensure that, upon their death, at least some of the property they brought into the marriage is preserved for their own children. In that context, spouses may enter into a contractual “mutual wills agreement” to ensure that their children are “looked after” in terms of their inheritance.

[45] To take as an example the case where only one spouse to a second marriage brings children to the marriage, and where that spouse has brought substantial property into the marriage, the spouses may agree, in an MWA, to execute, and not revoke, mutual wills which have the effect of –

(a) allowing the surviving spouse (that is, the second spouse to die, whoever that may be) full enjoyment of the property of the first spouse to die during their lifetime, with that property, or what remains of it at the death of the surviving spouse, to be distributed, by the survivor’s will, to the children brought into the marriage; or

(b) providing the surviving spouse with a life interest in the property of the first spouse to die, with that property to pass, upon the survivor’s death, by the survivor’s will, to the children brought into the marriage.[9]

[46] However, notwithstanding an MWA and the contractual promises made by each spouse to the other under it, a will is a revocable instrument. The law cannot prevent the surviving spouse from revoking their mutual will and making a new one which excludes the children of the first to die.[10] The law of probate can do nothing about fraud of this kind, committed by one party to the MWA upon the other. In the probate sense, the fraudulent spouse’s later will is effective as their operative will.

[47] However, if the doctrine of mutual wills applies – that is, if the MWA is contractual – equity will intervene. Equity will not permit the surviving party to an MWA to deal with the property the subject of the MWA in a way that is contrary to the MWA by revoking their mutual will and executing another. Notwithstanding the later will, equity will specifically enforce the MWA, including by way of imposing a constructive trust upon the property the subject of the MWA for the benefit of those to whom the property was ultimately promised.

[48] Even without revoking their mutual will, a surviving spouse may act apparently inconsistently with the MWA during their lifetime, by disposing of, or otherwise consuming, the inherited property, leaving nothing to pass to their step-children. Whether this entails a breach of the MWA or not is usually resolved by the terms of the MWA, although there is case law dealing with the situation where the MWA is silent about the extent to which the survivor must preserve the inherited property. If there has been a breach of the MWA by such failing to preserve, then that is another situation to which the doctrine of mutual wills may apply and equity may intervene.

Issues raised in this application and James’ authorities – overview [in Forster v Forster]

[49] The primary questions raised by this application are (a) whether a constructive trust arose upon the death of the deceased, casting Annabel as a constructive trustee of the property the subject of the MWA in the absence of fraud and, if so, (b) whether Annabel, as constructive trustee, ought to be required to account to James for her property during her lifetime. A careful analysis of the cases upon which James relied revealed that those issues were not directly addressed therein.

[50] As to (a), the cases upon which James relied, which directly invoked “the doctrine of mutual wills”, concerned a court being called upon to intervene to address a fraud – but there is no fraud alleged here.

[51] Also, as to (b), as mentioned, it was simplistic to assume that the success of the application hinged on Annabel’s characterisation as a constructive trustee. The suggestion that Annabel held the property, the subject of the MWA, as a constructive trustee in the absence of fraud raised obvious questions about the nature of Annabel’s alleged trusteeship which were not addressed by the applicant including: How could Annabel’s status as constructive trustee during her lifetime be consistent with her absolute ownership of the property? Given that she held the property absolutely, to what extent was she obliged to put the interests of the beneficiaries ahead of her own interests during her lifetime? What were her duties of management, or other obligations as trustee? And, critically, how was imposing upon Annabel an obligation to account to James for the property consistent with her right to beneficial enjoyment of it, albeit subject to the MWA? None of the cases upon which James relied dealt with the duties owed by a constructive trustee under the doctrine of mutual wills beyond the “duty” to convey the property in accordance with the terms of the mutual will, which “duty” was itself enforced by court order.

Analysis of the authorities upon which James relied [in Forster v Forster]

Dufour v Pereira (1769) 1 Dick 419; 21 ER 332

[52] This decision by Lord Camden is the foundational case on the doctrine of mutual wills. There are two reports of it. The first is in Juridical Arguments, published by Francis Hargrave, a barrister, in 1799. Hargrave’s report sets out the handwritten notes upon which Lord Camden based his judgment. The other later report, published in Dickens in 1803, is briefer.

[53] The facts of this case were as follows. Rene and Camilla Ranc were husband and wife. They executed a joint will (in 1745) which left the property of the first of them to die to their survivor for life; and the property of the survivor to their children and grandchildren upon the survivor’s death. Rene was the first to die. Camilla took under his will. Then she revoked the joint will and executed a new one, leaving her property to one daughter only. The question for Lord Camden was whether Camilla could validly revoke the joint will.

[54] Rene and Camilla executed their joint will in Europe but moved to England before Rene died. Such a will was not then known to the law of England, but Lord Camden determined that its operation fell to be decided by English law.

[55] I gratefully adopt McMillan J’s discussion of this case in Flocas v Carlson, as follows (my emphasis) –

102 Having been referred to civil law authority to the effect that notwithstanding the execution of such a document, in their lifetimes joint testators may in secret make a new will, his Lordship indicated that the English law could not be so:

The law of these countries must be very defective, and totally destitute of the principles of equity and good conscience: for nothing can be more barbarous than a law, which does permit in the very text of it one man to defraud another.

The equity of this court abhors the principle.

103 His Lordship then set out the principles that he saw as governing the operation of mutual wills under English law:

A mutual will is a mutual agreement.

A mutual will is a revocable act. It may be revoked by joint consent clearly [and] by one only, if he give notice, I can admit.

But to affirm, that the survivor (who has deluded his partner into this will upon the faith and persuasion that he would perform his part) may legally recall his contract, either secretly during their joint lives, or after at his pleasure, I cannot allow.

The mutual will is in the whole and in very part mutually upon condition, that the whole shall be the will. There is a reciprocity, that runs throughout the instrument. The property of both is put into a common fund, and every devise is the joint devise of both.

This is a contract.

104 The focus, for Lord Camden, was on Camilla’s right to revoke the joint will, as is apparent from the following passages:

If not revoked during the joint lives by any open act, he that dies first dies with the promise of the survivor, that the joint will shall stand. It is too late afterwards for the survivor to change his mind, because the first dier’s will is then irrevocable, which would otherwise have been differently framed, if that testator had been apprised of this dissent.

Thus is the first testator drawn in and seduced by the fraud of the other, to make a disposition in his favour, which but for such a false promise he would never have consented to.

105 Lord Camden also considered an argument put by Camilla’s daughter that the parties, knowing that wills by their very nature are revocable instruments, could not have intended a promise not to revoke:

It was argued however, that the parties, knowing that all testaments were in their nature revocable, were aware of this consequence, and must therefore be presumed to contract upon this hazard.

There cannot be a more absurd presumption than to suppose two persons, while they are contracting, to give each licence to impose upon the other.

Though a will is always revocable, and the last must always be the testator’s will, yet a man may so bind his assets by agreement, that his will shall be a trustee for performance of his agreement.

106 According to Lord Camden, there was no relevant difference between a contract to dispose of assets by will in a certain fashion, and a contract not to revoke a will already disposing of assets. Both would be enforced, not by operation of the will, but by performance of the agreement:

The court does not set aside the will, but makes the devisee heir or executor trustee to perform the contract.

107 His Lordship then referred to three existing cases to the effect that, where in return for a promise by a testator to make (or leave) a certain party as executor, that executor promised to pay certain legacies:

This court bound the will with the promise, and raised a trust in the devisee.

The act done by one is a good consideration for the performance of the other.

This case stands upon the very same principles.

The parties by the mutual will do each devise, upon the engagement of the other, that he will likewise devise in a manner therein mentioned.

108 His Lordship then considered how such an agreement must be proved:

The instrument itself is the evidence of the agreement; and he, that dies first, does by his death carry the agreement on his part into execution. If the other then refuses, he is guilty of a fraud, can never unbind himself, and becomes a trustee of course. For no man shall deceive another to his prejudice. By engaging to do something that is in his power, he is made a trustee for the performance, and transmits that trust to those that claim under him.

This court is never deceived by the form of instruments.

The actions of men here are stripped of their legal clothing, and appear in their first naked simplicity.

Good faith and conscience are the rules, by which every transaction is judged by this court, and there is not an instance to be found since the jurisdiction was established, where one man has ever been released from his engagement, after the other has performed his part.

109 Finally, Lord Camden conceded he may have ‘given myself more trouble than was necessary’, concluding that by probating the mutual will, and taking the benefit under the will, Camilla was estopped from denying that the mutual will bound her.

[56] The brief Dickens report concluded as follows –

The defendant Camilla Rancer hath taken the benefit of the bequest in her favour by mutual will; and hath proved it as such; she hath thereby certainly confirmed it; and therefore I am of the opinion, the last will of the wife, so far as it breaks in upon the mutual will is void.

And declare, that Mrs. Camilla Rancer having proved the mutual will; after her husband’s death; and having possessed all of his personal estate, and enjoyed the interest thereof during her life, hath by those acts bound her assets to make good all her bequests in the said mutual will; and therefore let the necessary accounts be taken.

[57] In my view, this case does not support James’ argument that Annabel is a constructive trustee during her lifetime in the absence of her breach or threatened breach of the MWA, requiring her to account to him for the property. Rather, this case suggests that, by virtue of the principles of equity, a survivor will be converted into a trustee if he or she commits a fraud by refusing to carry out his or her part of the MWA (cf “if the other then refuses, he is guilty of a fraud, can never unbind himself and becomes a trustee of course” and “there is not an instance to be found since this jurisdiction was established, where one man has ever been released from his engagement, after the other has performed his part”).

Birmingham & Others v Renfrew & Others (1937) 57 CLR 666

[58] This case is considered the “landmark” Australian case on mutual wills.

[59] Grace and Joseph Russell were married. Grace was the beneficiary of a large inheritance. Joseph had no property. Grace and Joseph agreed that – instead of her making a will leaving him her property for life; and then to certain relatives – she would (after certain legacies) leave the residue to him, upon his promise that he would leave the property which he inherited from her to her relatives.

[60] In accordance with their agreement, on 31 March 1932, Joseph made a will in which, after the payment of certain debts and expenses, he left the balance of his estate to Grace and, in the event of her not surviving him, to four of her relatives. He agreed with Grace not to alter his will. Also, in accordance with their agreement, on 1 April 1932, Grace made a will in which, after providing for certain legacies, she left the residue to Joseph; and in the event of his not surviving her, to the same four of her relatives (“Grace’s Relatives”).

[61] On 26 July 1932, Grace died. Joseph took an annuity under her will, and the residue. Thereafter, he changed his will several times. His final will was to the benefit of his own relatives at the expense of Grace’s Relatives.

[62] Grace’s Relatives alleged that Joseph’s will of 31 March 1932 was made in pursuance of a binding agreement with Grace as to how he would dispose of her property, in consideration of which she made her will which left him the benefits which he had accepted. Grace’s Relatives sought (amongst other relief) enforcement of the agreement, or a declaration that Joseph’s executors held his estate on trust for them.

[63] Joseph’s relatives, who benefitted under his final will, denied that a binding agreement existed between Grace and Joseph.

[64] The primary judge held that the agreement was enforceable: it was for the benefit of Grace’s Relatives, who were entitled to enforce their rights. However, the primary judge did not explain the basis of their rights.

[65] Joseph’s relatives appealed to the High Court. They argued that there was no such thing as specific performance of an agreement to make a will; and that a third party could not enforce an agreement to which they were not a party. They argued that a promise not to revoke a mutual will was not enough to create equitable interests; and that the freedom to deal with property during the life of the survivor, as per the will, was inconsistent with the creation of an equitable interest.

[66] Grace’s Relatives submitted inter alia that in the case of mutual wills, equity will restrain the parties from doing anything in fraud of the agreement.

[67] The High Court found that Grace and Joseph had entered into a mutual wills agreement, and imposed a constructive trust upon Joseph’s executor to perform the agreement.

[68] Latham CJ found that the case fell within the principles enunciated by Lord Camden in Dufour v Pereira. As Grace’s Relatives conceded, the agreement between Grace and Joseph did not have the effect of preventing Joseph from dealing with the property he received from Grace during his lifetime. This meant that any trust could only be a kind of floating trust which finally attached to the property he left upon his death.

[69] His Honour continued at 676 (footnotes and citations omitted, my emphasis) –

… The law was stated with robust simplicity in 1769 by Lord Camden in Dufour v Pereira, where, speaking of a mutual will made by husband and wife he said: “It might have been revoked by both jointly; it might have been revoked separately, provided the party intending it, had given notice to the other of such revocation. But I cannot be of opinion, that either of them, could, during their joint lives, do it secretly; or after the death of either, it could be done by the survivor by another will. It is a contract between the parties, which cannot be rescinded, but by the consent of both. The first that dies, carries his part of the contract into execution. Will the court afterwards permit the other to break the contract? Certainly not.” In that case it was declared that the wife, “having possessed all his personal estate, and enjoyed the interest thereof during her life, hath by those acts bound her assets to make good all her bequests in the said mutual will; and therefore let necessary accounts be taken”. This case was very fully discussed in Hargrave’s Juridical Arguments (1799) vol. ii., and what that learned author has said has been recognised as law on a number of occasions and as applying to cases of separate wills made by two persons. I have already referred to Gray v Perpetual Trustee Co. See also Stone v Hoskins, where the following passage is quoted from Hargrave: “Though a will is always revocable, and the last must always be the testator’s will; yet a man may bind his assets by agreement that his will shall be a trustee for performance of his agreement. … These cases are common, and there is no difference between promising to make a will in such a form and making a will with a promise not to revoke it. This court does not set aside the will; but makes the devisee heir or executor trustee to perform the contract.” …

… Upon the basis of the law as declared in the authorities mentioned and upon the finding of fact made by the learned judge, an order was made declaring that Grace Alexandra Russell entered into the alleged agreement as trustee for and on behalf of the plaintiffs and that the agreement is binding upon and enforceable against the executors of the husband. In my opinion this order is appropriate in it terms.

[70] James relied particularly upon the judgment of Dixon J at 687 – 690. Annabel urged me to consider Dixon J’s comments in context, in which case I would appreciate, she submitted, that any trust was one imposed by equity to prevent a fraud only.

[71] At 683, his Honour said

… It has long been established that a contract between persons to make corresponding wills gives rise to equitable obligations when one acts on the faith of such an agreement and dies leaving his will unrevoked so that the other takes property under its dispositions. It operates to impose upon the survivor an obligation regarded as specifically enforceable. It is true that he cannot be compelled to make and leave unrevoked a testamentary document and if he dies leaving a last will containing provisions inconsistent with his agreement it is nevertheless valid as a testamentary act. But the doctrines of equity attach the obligation to the property. The effect is, I think, that the survivor becomes a constructive trustee and the terms of the trust are those of the will which he undertook would be his last will …

[72] His Honour then spent some time explaining the way in which obligations attached to each party to an MWA, quoting from an opinion by Hargrave contained in Juridical Arguments[11] in which, his Honour said (at page 684) the author gave “in a sentence” the principle upon which MWAs are enforced in favour of the beneficiaries, as follows (my emphasis) –

“ … the simple question is, whether a court of equity shall suffer this breach of the compact to be available: or whether, under its jurisdiction of compelling specific performance, the court shall not declare the earl’s devisees deriving under a breach of contract to be mere trustees for those against whom that breach operates.”

[73] In another quote from the opinion set out in Dixon J’s judgment at 685, there is a reference to equitable relief by way of a decree of specific performance in the face of breach; and, for that purpose, the conversion, into trustees, of the promising party and the volunteers deriving under him (my emphasis) –

“… [T]he plain inference seems to be, that compacts or agreements, upon the faith of which wills or settlements are either made or forborne to be made, are enforceable by both jurisdictions: and that as at law damages are recoverable by those injured by the breach; so in equity a more perfect relief is given, by decreeing specific performance, and for that purpose, whenever the case requires converting the party promising and all volunteers deriving under him into mere trustees of the property in question. So anxious also do our courts of equity appear to have been in exacting the performance of such compacts, that even verbal promises have had enforcement; the Statute of Frauds having been refined upon, to prevent the requisition of writing from operating; and entering into such engagements and then refusing to perform them having for that purpose been classed, as a fraud upon the testator or other party influenced in his conduct by the particular promise” …

[74] At 686, Dixon J observed that the principles upon which Hargrave based his arguments had passed into the modern law. His Honour continued, emphasising equity’s intervention to provide relief (my emphasis, citations and footnotes omitted) –

It is true that they date from a period when neither at law or in equity was the view firmly applied that no one but a party to a contract could enforce it. Indeed this proposition never became true in equity; for, if a contracting party made himself trustee for others of the benefit of the obligation and it was a contract enforceable by equitable remedies, then the beneficiaries of the trust could obtain those remedies on a properly framed suit in which the contracting party so making himself a trustee was joined. Since the Judicature Act, it is possible for the beneficiaries of a purely legal chose in action to enforce it in a similar manner … But in a contract for corresponding or “mutual” wills, the equities arise from a combination of circumstances. In the first place, the obligations of the survivor under such a contract have always been regarded as enforceable in Chancery. Necessarily the remedy could not be the same as that by which executory contracts are specifically performed. In such cases the party is compelled to carry out his contract according to its tenor. But the relief was specific and was framed to bring about the result intended by the contract.